The Practice and Politics of Archival Labour in Histories of Queer Art in Britain

The Practice and Politics of Archival Labour in Histories of Queer Art in Britain

-

Fiona Anderson

-

Radclyffe Hall

-

Nazmia Jamal

-

Conal McStravick

-

Francesco Ventrella

-

James Bell

Introduction by

-

Fiona AndersonSenior Lecturer in Art HistoryNewcastle University

Introduction

The importance of community-led collecting and preservation work to histories of queer art in Britain during and since the 1980s cannot be underestimated. From the LGBTQIA+ Archives at the Bishopsgate Institute in London to Glasgow Women’s Library and the Lavender Menace Queer Books Archive in Edinburgh, grassroots curatorial and archival work has informed how queer art across Britain has emerged as a field of art-historical study and a topic of curatorial and artistic enquiry. Archival material relating to queer British art and life, whether displayed in vitrines or reimagined by artists in new works of art or by curators through creative curatorial practices, has played important roles in several recent exhibitions and artist-led projects, including Hot Moment: Tessa Boffin, Jill Posener, and Ingrid Pollard at Auto Italia in London in 2020, curated by Radclyffe Hall; Ajamu: Archival Sensoria, curated by Languid Hands, at Cubitt in London in 2021, and Digging in Another Time: Derek Jarman’s Modern Nature at the Hunterian Art Gallery in Glasgow in 2024–25.

This feature draws attention to archival collections and practices of collecting and care in queer art. Each contributor was invited to choose an archival object pertinent to the history of queer art in Britain since the 1980s, and to consider its relationship to the themes of archival labour and care. Some of the objects they have chosen sit outside academic institutions, galleries, and museums; others are located in significant national and international institutional collections, or have a complex and precarious relationship to them. Together, the stories of these objects, and the broader queer histories they speak to, demonstrate how and why grassroots, community-led archival work shapes how histories of queer British art and cultural production have been and are preserved, shared, accessed, and made visible, and to whom.

Kate Eichhorn has suggested that interest in the archive “both as subject of inquiry and creative locus for activism and art” emerged under neoliberalism “as an attempt to regain agency in an era when the ability to collectively imagine and enact other ways of being in the world has become deeply eroded”.1 As queer art in Britain since the 1980s is historicised and recognised in British academia and in museums and galleries with growing frequency, even as the arts funding landscape remains precarious, this feature explores how archival material that speaks to histories of queer art in Britain may be shared ethically and considers the material and emotional labour that underpins this work and that will sustain it in the future.

1Contribution by

-

Radclyffe HallRadclyffe Hall, a group of artists and writers dedicated to exploring culture, aesthetics, and learning through the lens of contemporary feminism.

Ingrid Pollard, Performance Outside The Fridge, Brixton, circa 1990

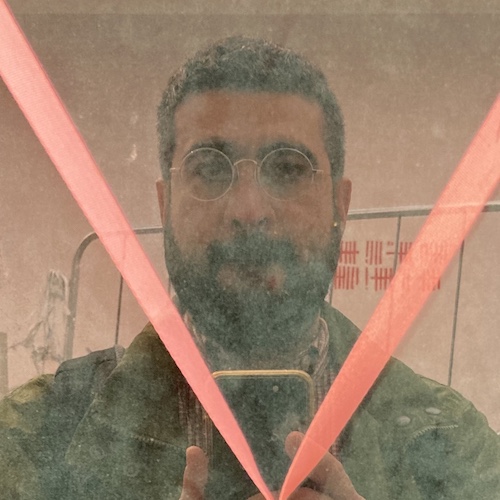

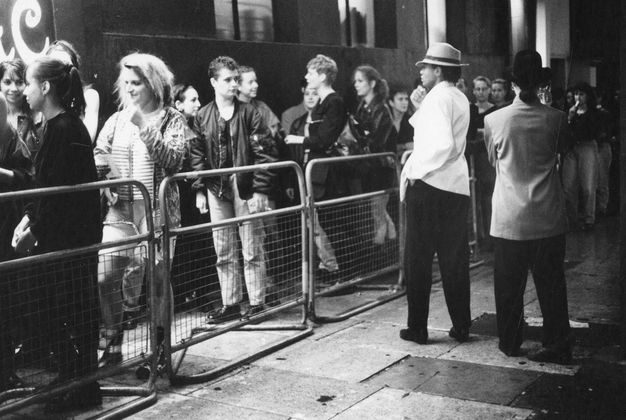

This photograph by Ingrid Pollard organises the architecture of city nightlife within a single frame (fig. 1). Metal barriers bisect a pavement, dividing the street into two spaces. In one, a queue shuffles towards the entrance of a nightclub; in the other, passers-by watch them. On the threshold between these two spaces something unfolds: a figure swaggers down the line in an oversized zoot suit and a fedora. The event is ambiguous, identified more by the photographer’s presence than by what is taking place in front of her lens. Her presence enables this moment of recognition and regard, interaction and complicity. A question passes down the line: “Has the performance already begun?”

Performance Outside The Fridge, Brixton was made circa 1990. It is a black-and-white image printed on the warm fibre-based paper preferred by Pollard at the time, one of a number she produced as the in-house photographer for Club Sauda. Sauda was a Black women-only cabaret that ran monthly at various venues across London in the same period. The artist Ain Bailey, who can be seen in the queue, tells us that this is not an image from a Sauda-run night because it shows a decidedly mixed audience.2 Instead, these people are standing in line for Venus Rising, a regular Thursday dyke club at The Fridge, a long-time hub for countercultural Black and queer nightlife that had opened in Brixton in 1981. The Club Sauda performers are guests here.

2This is an image of a meeting place (the queue) and a stage (the street). In queer culture, the nightclub often figures as an important space of communal visibility, a space of shared production and performed desire. The integrity and safety of a building, of a crowd, and who is permitted into either, who gets to be on the list, why we need the dark in the first place—these are issues with answers that stratify and structure queer living as much as belonging. Clubs provide answers as places of escape but, as Pollard’s photograph depicts, we are not yet in. Prior to nightclub entry, this street-as-stage presents a complex set of dynamics. For one, the queue-as-audience is contingent: it conjures up a feeling of anticipation, of moving and meeting, of exclusivity and style. “The queue was iconic”, Katherine Griffiths, a DJ at Venus Rising, recalls, recounting the chatting, the spliffs, the excitement.3 In this line, dyke fashions of the day are on display: bomber jackets, jeans, and leather. On the pavement, the Sauda performer struts the barrier in anachronistic dapper gangster drag. This dragging draws a line backwards from the dyke club in Brixton in the early 1990s to the Harlem Renaissance in New York in the early twentieth century.

3Pollard originally trained in film and video; her approach to photography is often grounded in cinema, in the pleasures of performing and looking. She describes her still images as “flirting” with the idea of moving images, recognising that “cinematic vision … continues to leak into my photography”.4 Performance Outside The Fridge, Brixton plays with the formal tropes of film noir. Like cinema, this photograph belongs to a sequence of images taken that night that narrate the action. The photo series shows the suit-clad Sauda performer joined by another performer, both eyeballing their impromptu audience. Pollard recalls photographing these figures walking the line, occasionally singling out a woman to skip the queue as their privileged gangster’s moll. She describes the performance’s “hyper-masculine” edge, where the performers parodied misogynistic and violent gestures from the city streets that would have been familiar to women.5 Physically dragging queuing women from the line into the street, the performers’ drag engages debates about representations of violence that predominated in feminist (and photographic) communities at the time. Lorna N. Bracewell argues that the historicisation of this period, which has come to be known as the “sex wars”, has failed to attend to questions of racialisation and largely neglected or reduced the contribution of Black feminists to contemporaneous debates.6 In contrast, Performance Outside The Fridge, Brixton is a point of access that registers racial dynamics and a Black lesbian feminist critique of sexual violence. This performance and its images illuminate how various vectors—cultural materials, performative techniques, physical encounters—intersect.

4At the centre of these interactions is the photographer. Pollard describes the evolution of her participation in spaces such as Sauda:

7It was by now commonplace for me to be with a camera and I realised that what developed from this was a personal aesthetic of the “snap-shot”, the fleeting exposure of a split second, capturing the hot moment of a performance. During the eighties I was working with and photographing actors, dancers, writers and theatre companies. It was a world of fantasy and make believe where the detail of a gesture or the caress of light on a shoulder were part of the alchemy that captured my attention. It still holds me intrigued whenever I gaze at the stage cinema screen or look through the camera view-finder.7

The alchemy of Pollard’s “hot moment” runs through the Fridge photo series—in the momentary glances between subjects, in the ephemeral nature of a street performance acted out for the temporary community of the queue, and in the physicality of the photograph itself. The surface of the print has warmth: its yellow tone simulates the sodium glow of the Brixton streetlamps that spills onto the shuffling queue and the rows of circular spotlights that are embedded in the canopy of the club entrance.

This photograph and the rest of the series sit within a larger constellation of artefacts that make up the archive of Club Sauda. Informal, ephemeral, semi-public, this archive could be likened to the queue but, unlike a queue, its materials do not line up neatly on the shelves of the institutional repository; they remain highly dispersed. In conversation with the curator and writer Taylor Le Melle, Pollard referred to the Sauda materials as parts of a “strange archive”, noting its current existence as numerous videos and photographs, distributed between various people across the United States and the United Kingdom.8 When Le Melle asked Pollard if she would ever consider donating her Sauda archive, and what institution might be a suitable home for it, Pollard’s swift response was “It’s not mine to give”. Such dispersion reflects the continuities between the spontaneities and creative improvisations of Sauda as event and Sauda as archive. The club generated spaces for Black women’s creativity to exist on their own terms. Inviting participation through open call, Sauda described itself as “a place for exchange of smiles, laughter, love, dance, music, poetry, song, theatre, information, wisdom and truth”.9 Pollard’s recollection of people “rocking up” to the club resonates with how she describes her photographic practice from this time: “It was a club of artists passing through … How people came was very random. ‘I want to do my poetry, I want to dance’”.10

8Numerous Sauda performances were recorded on video by Yvonne Sanders-Hamilton and photographed by Pollard, offering an internal visibility that was crucial to shoring up temporary communities that were otherwise subject to periodic dispersion and ongoing precarity. This performing and imaging necessarily occurred in tandem with Sauda artists’ individual practices, their work circulating variously through live theatre, gigs, club spaces, book fairs, and spaces of political protest. Pollard’s Sauda photographs have recently been the subject of public recirculation via a series of exhibitions and publications from 2019 onwards.11 (This includes Hot Moment, a group exhibition staged at London’s Auto Italia, organised by Radclyffe Hall, which presented photographs and video from Sauda nights. The staging of this informed many of the key concerns of this article.) Given the resurgence of interest in participants of Club Sauda and their work, it is worth noting the tight circuit of display that such images initially occupied: Pollard’s portraits of Sauda performers were first exhibited in the context of the club itself, the exhibition of which was, in turn, documented by Sanders-Hamilton’s video camera.

11Club Sauda had no regular address; it moved between venues and, as is evident in the Fridge series, it occupied the street as well as the stage. But the club’s description as a “place of exchange” underscores its commitment to building up mutual visibility and shared spaces of production, and to celebrating the expressions of a by-and-for community. This communal place-making is evident in the role of Pollard and Sanders-Hamilton as in-house documentarians, or artists-in-residence, whose cameras performed the work of making, shaping, and staging a community for the performers and audience that made up their subjects. The titling of these roles has a playful institutional ring, just as the “Club” of Sauda invokes a geographical location. But there is a strategic seriousness to these words. Pollard’s practice has frequently and consciously sought out the idea of the artist-in-residence as a condition of production, as well as a means by which to position her practice in direct connection with communities:

12There are aspects of residencies which produce a sense of a shared intimacy with geography, and of simultaneously being both an insider and an outsider. Through being part of the “co-production” of a landscape and a community for a period of time, in a sense people “are” where they go. The lived experience of being “there” is part of an evolving research practice reliant on a multiplicity of factors; of class, economics, place, gender, ethnicity, which counters the conservative notion of “rootedness”. The experience of the artists’ residency has a value and power attached to it through engagement in and being part of the scattered complexity of many voices, through a willingness to be immersed, to be part of interaction and exchange.12

In recent exhibitions, Pollard has printed Performance Outside The Fridge, Brixton on a diminutive scale, 4 × 8 inches. Viewers who do not have “the lived experience of being ‘there’” are required to push themselves up against this image and its high-contrast grain without guarantee of full and easy comprehension. This is a partial snapshot that rejects easy consumption—perhaps because it was produced from an impetus (and within a community) that is uninterested in mainstream forms of cultural capture.

At a representational level and a material one, the photograph stages questions that are pertinent to queer labour, access, and queer archival practices: Who gets it? Who gets in? The question so explicitly asked in this series of photographs outside the Fridge—When does the performance begin?—is central to feminist and queer studies. (In addition, “When or where is the event taking place?” is a question that is central to a strain of photo theory.) Situating our analysis from within the photograph’s context of production, this image can be understood as a negotiation between photographer and performing subject, where complicity (rather than consent) is part of the agreement to show up as co-producers, to participate in an ongoing performance that is not limited to the documented event but rather is a form of communal culture-making that limits access in order to enjoy intimacy.

Partialness, dispersion, mixed guardianship, and acts of restriction and refusal can be important and powerful acts of preservation that work against practices of extraction and presentation. Regardless of the intention of the institutionalising museological archive, dispersed and unorganised archives have an in-built security that refuses capture. This is not to romanticise the precarity of archives while acknowledging the precarity of the conditions under which they exist. The re-presentation of elements of the Sauda archive, including this photograph, raises ongoing concerns about the systematic, indexical forms of knowledge that gain their value from the accrual of evidence, especially the discomfort caused by the application of the term “evidence” (or even “object”) when what we mean is “people”. While images such as Performance Outside The Fridge, Brixton circulate among wider audiences and in contexts different from those for which they were originally intended, the question “When does the performance begin?” unfurls into other pressing questions, such as what ethics of presentation the material demands of curators, collectors, and researchers wishing to publish these images.

In her acceptance speech for the prestigious Hasselblad Award on 11 October 2024, Pollard said: “A student, two days ago, asked for hope in her future, and I said to her, build your alliances, build your posse, build your gang, your future. They will offer solace for the hard times and celebration for the good ones”. “Gang”—a word usually deployed by authorities to redefine informal communities as nuisances and even threats to public safety, is deployed here by Pollard to emphasise instead an ethos of grassroots working, a language of collaboration and co-production, and communal living.13 The materials of alliance for hard times can be equally applied to history and to access: the work to form relationships, to build safer and celebratory communities within which stories can be shared and remembered. Protagonists are called up, asked questions that probe their memories. Likewise, these materials can disturb the new orthodoxies that might otherwise set up barriers to future access.

13Contribution by

-

Nazmia JamalPaul Mellon Centre New Narratives Doctoral Scholar, 2025--28

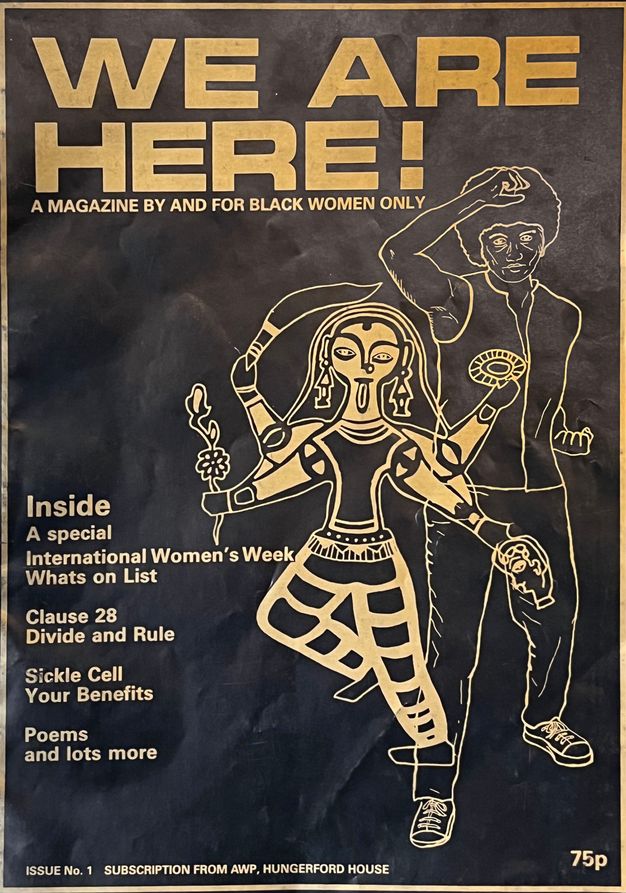

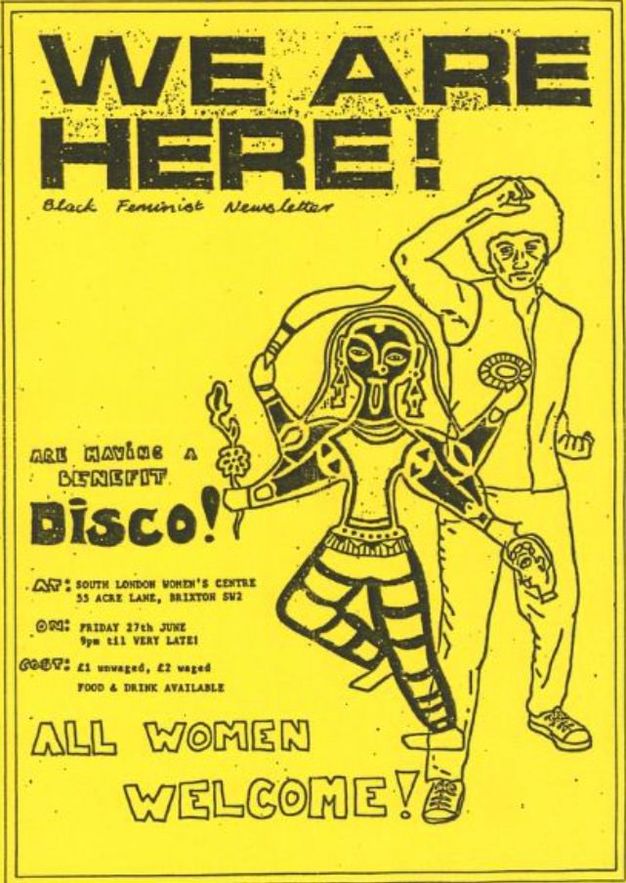

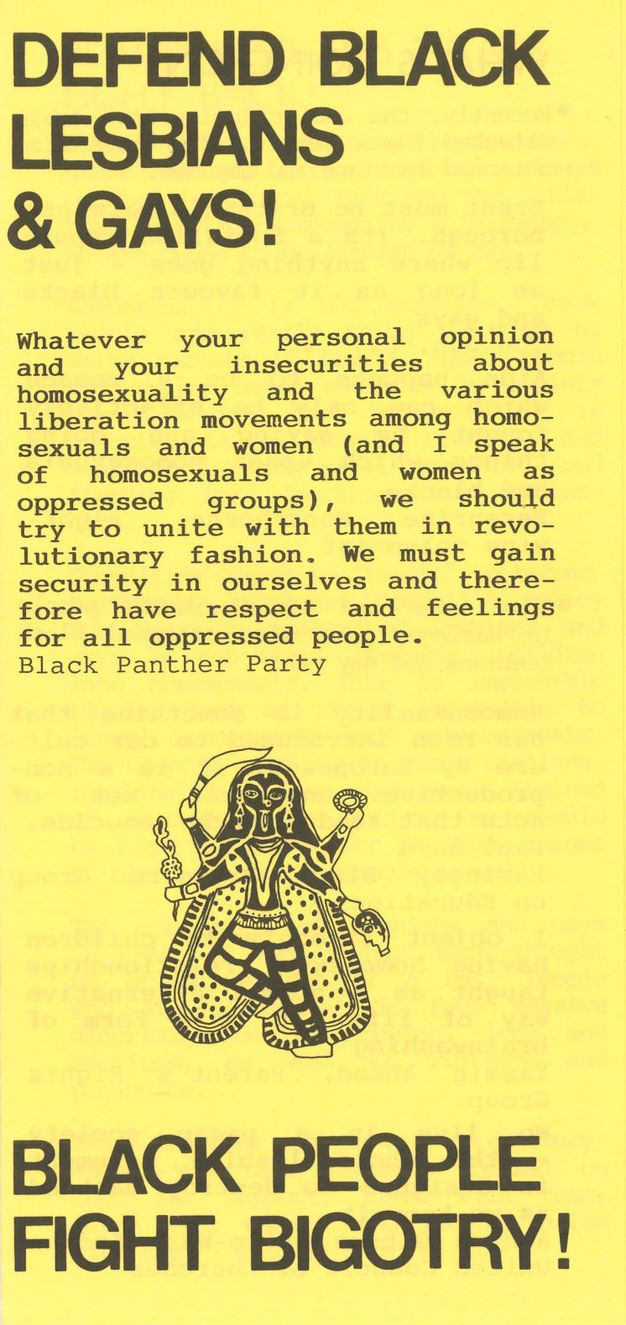

Shaheen Haq, Kali, 1984

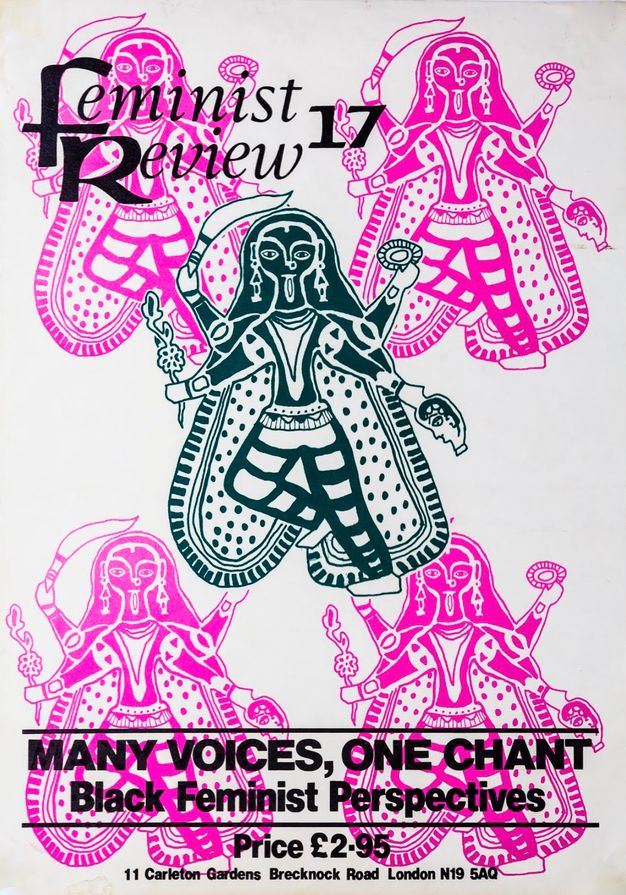

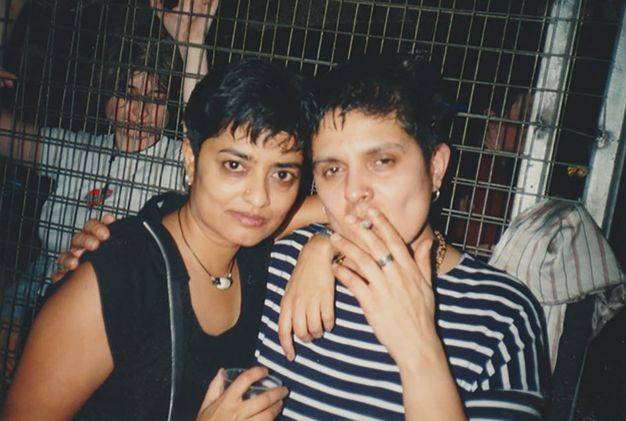

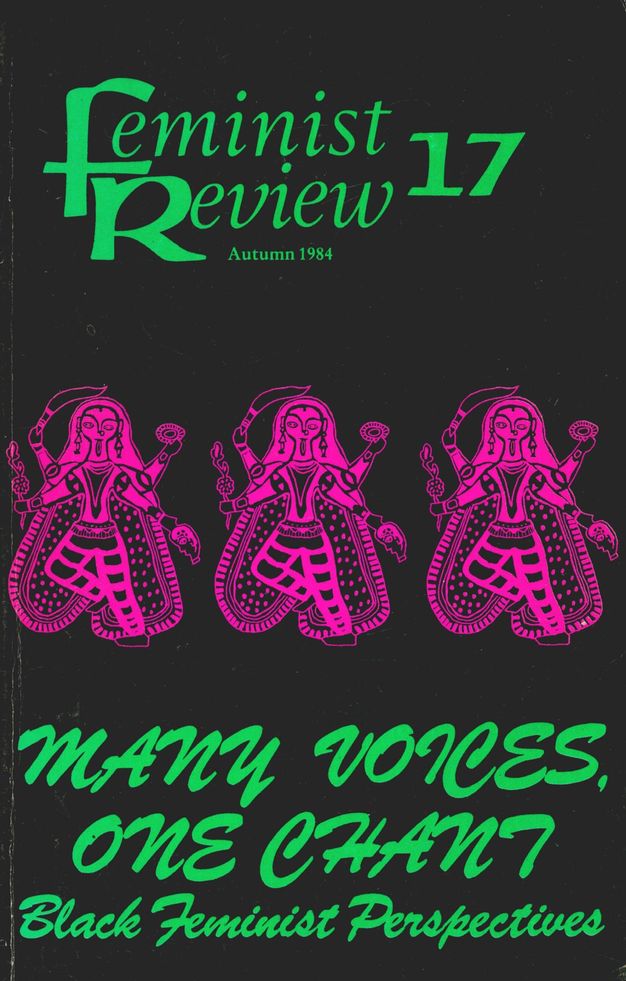

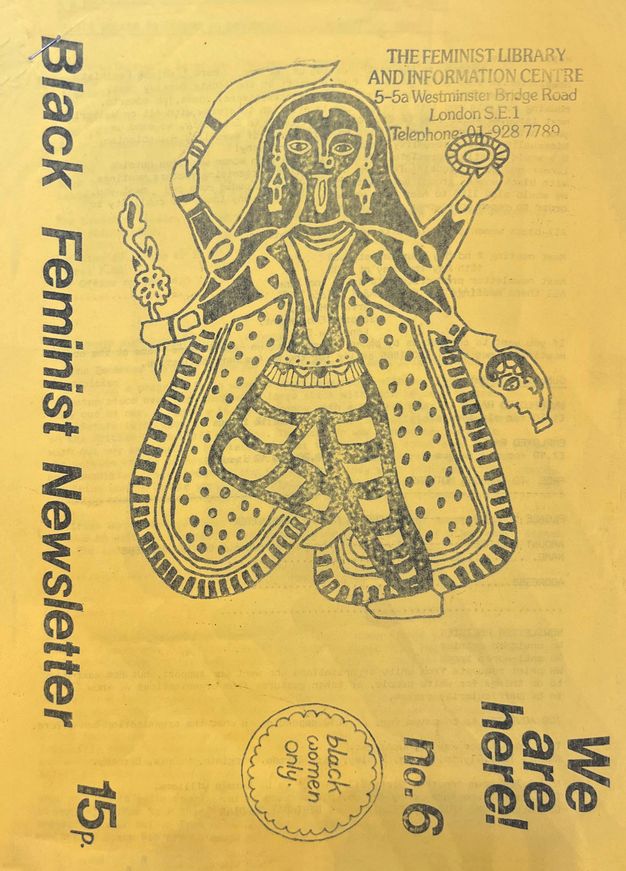

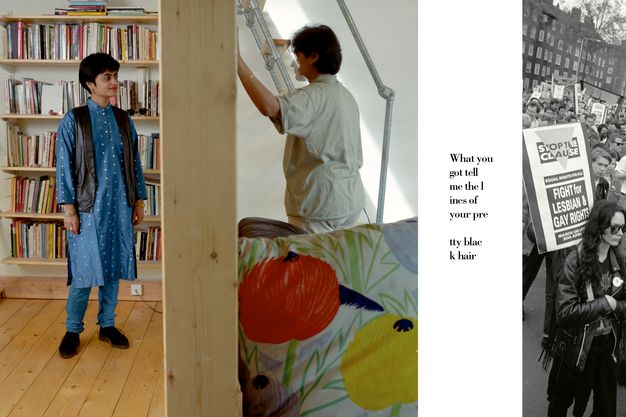

The subject of this piece may or may not be in the personal archive of the person who made it forty years ago. She thinks she may be able to put her hand on it, but they are redoing their kitchen at the moment, so accessing old boxes is a bit tricky. The object in question is a drawing of the Hindu goddess Kali, tongue stuck out, right foot raised, veil spotted and flared, earrings dangling, and held in her four hands the traditional khadga, trishul, kapāla, and severed head (fig. 2). She was drawn by Shaheen Haq (fig. 3) for the cover of Feminist Review 17, no. 1 (fig. 4), with Rotring Isograph pens, which were more usually deployed in making architectural drawings. This was a special issue published in 1984, titled “Many Voices, One Chant: Black Feminist Perspectives”, edited by a guest editorial group made up of Valerie Amos, Gail Lewis, Amina Mama, and Pratibha Parmar. For many Black feminists in Britain the image of a hot pink Kali, repeated three times against the black of the cover of this issue, is synonymous with a particular kind of politically Black anti-imperial and lesbian-inclusive (indeed lesbian-led) feminism that developed in Britain during the 1980s. Across the decade Haq’s drawing was often deployed and without attribution, and an incarnation of Kali has gained an independent life of her own as an icon copied, cut, and pasted by Black feminists across the United Kingdom onto posters, leaflets, newsletters, and magazines, to signal particular solidarities and politics (figs. 5–8).

In 1984 Haq was, in her own words, “pushing 30”, working as an architect at Haringey Council, and firmly rooted in Black feminist spaces including being present at the first Black lesbian gathering at the Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent (OWAAD) conference held in London in 1981.14 She was living in a Housing Association flat on Canonbury Road in Islington with her partner, the film-maker Pratibha Parmar (fig. 9). Along with Parmar, Ingrid Pollard, and Viv Bietz, Haq was part of the Late Start Collective who in 1985 filmed a discussion with Audre Lorde in Haq and Parmar’s home.15 Today, Haq is perhaps best known for her film collaborations with Parmar; since 2000 they have run Kali Films. Haq produces landmark feminist films about icons such as Alice Walker and Andrea Dworkin that are directed by Parmar. Their collaboration began with Parmar’s earliest films, where Haq acted as production designer on Emergence (1986) and Sari Red (1988), in which she also appears. When Parmar and the rest of the guest editorial collective began putting together Feminist Review 17, they felt strongly that the look of the issue needed to make a definite break from Western art practices. Haq was brought in to work on visuals from the start, contributing illustrations and photographs and ultimately handling the layout for the entire issue.

14

Haq knew she wanted the cover to be joyful and defiant to mirror the developing content of the issue. As a powerful symbol of female empowerment and transformation, Kali was an obvious choice. Haq recalls that, at the time, feminist artists and activists in the South Asian diaspora, such as Sutapa Biswas, Pratibha Parmar, and Southall Black Sisters were using Kali to represent their commitment to self-determination and transformation while retaining or reclaiming the iconography of their home cultures. Using images of Kali was a way to call on the Shakti she embodies to lend energy and power to their movements. Haq’s iteration of Kali, inspired by an old poster by a rural Madhubani artist from Bihar that hung in the home she shared with Parmar, shows her as a creator rather than as the more typical destroyer. The intricate but bold image appears not just on the cover of Feminist Review 17 but also inside it, this time as a small black drawing on a white background, which was easily photocopied and used by others.16 It is this black-lined image (likely enlarged) that appeared on the cover of the initially London-based Collective’s newsletter We Are Here! (1984) and later, minus her veil, on the cover of the Leicester-based reincarnation of We Are Here! (1988) as a magazine.

16Many years ago, on a trip to the Lesbian Archive at Glasgow Women’s Library, I opened a box that was part of the Camden Lesbian Centre and the Black Lesbian Group’s collection and found myself staring at a pile of paste-ups: layouts of issues of the 1980s feminist magazine Outwrite. When I landed on the idea of writing about Haq’s Kali for this special issue, I thought I would be able to find the original paste-ups for that issue of Feminist Review. I emailed historian and art historian friends who might know where these could be. I was put in touch with several women, including Helen Crowley, who vividly recalled crawling around on the floor, putting together other issues to be sent to the publishers, but ultimately everyone seemed to agree that the manuscripts were probably never returned from the printer.

Not ready to give up, I turned to the Women’s Library at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and was pointed in the direction of Mary McIntosh’s archive, which includes an array of information about the Feminist Review. However, the only thing to be found relating to the artwork for issue 17 in McIntosh’s archive was a small controversy, in the minutes of a meeting, over the number of colours to be used in printing the cover. It was usual for covers to be printed in two colours, but the guest editorial collective insisted on realising Haq’s vision in three colours to create a strong visual impact. In the end, the publishers of Feminist Review reluctantly relented and spent an additional £116 on the chosen colourway of pink, green, and black.17

17Finally, I took to Instagram to ask if anyone I knew had ever stumbled across Feminist Review paste-ups or covers in their visits to archives. I posted my question on the same day that I happened to be attending an event to celebrate Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s book about Audre Lorde at the 198 Gallery in Herne Hill. One of the organisers of the event, Barby Asante, replied to my post explaining that the Feminist Review now had an office and potentially an archive upstairs in the gallery. I followed up this lead with Nydia Swaby but there are no paste-ups or original drawings to be found in their office. Later that day, outside Herne Hill station, I bumped into Haq who was also on her way to the event. The kitchen was still being done, she explained, but she was sure she still had Kali somewhere and could look when things were less chaotic. At the event, Gumbs read an extract from her book: “And so, in what looks like a living room, Audre sits in the sliver of moon made by folding chairs …”.18 I smiled at Haq, knowing that it was her living room in which this feminist history was made.

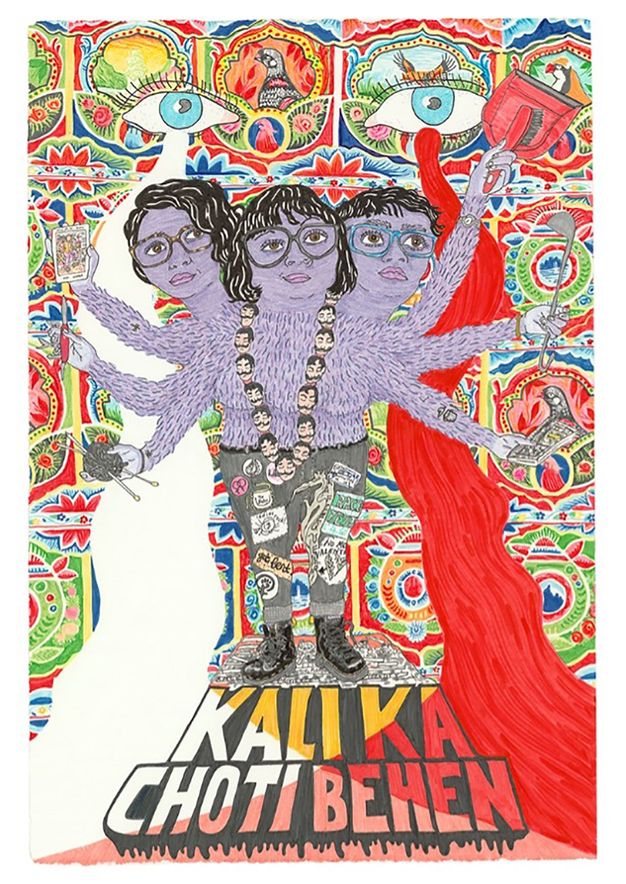

18My own first encounter with Feminist Review 17 and its iconic cover took place in the living room of the house Haq and Parmar currently live in. I first met them both in 2008 at the London Lesbian & Gay Film Festival. It was my first year as a programmer and on opening night I was excited to meet these glamorous brown lesbians who made movies. Eventually we became friends, and Pratibha and Shaheen sometimes took on older sister roles to my enthusiastic desi dyke, a choti bhen (little sister) keen to learn everything there was to know about Black feminist herstory and their adventures in the 1980s. In August 2011 they invited me over for dinner. The day before, Shaheen sent me an email: “Do you want to bring a small rolly bag? We have some great books you might like”. I left with a copy of Feminist Review 17 in my dutifully brought tote bag and a dangerously sharp vegetable peeler that was going spare. “Many Voices, One Chant: Black Feminist Perspectives” remains one of very few available texts that engage with Black British feminism and lesbian identity. My first reading of it, nearly thirty years after its publication, confirmed and shaped who I am and the community I was already part of. While I have always understood the impact the issue’s written content has had on my identity, it has been only more recently that I have realised how Haq’s feminist Kali has lodged in my mind. In pre-pandemic London I met with the Australian artist Texta Queen, who was planning a series of portraits of South Asian diaspora queers in Britain called Bollywouldn’t. Over several months we discussed concepts for the poster and agreed that I would be portrayed alongside Heena Patel and Humaira Saeed, friends I had grown up with in queer feminist space. The resulting portrait is of us as a three-headed goddess, Kali Ka Choti Behen, literally Kali’s little sister (fig. 10).

Contribution by

-

Conal McStravickPhD candidate in Arts & Visual and Material CulturesNorthumbria University

Stuart Marshall, Kaposi’s Sarcoma (A Plague and Its Symptoms), 1983

Stuart Marshall, the English LGBTQIA+ video artist, critic, curator, educator, and co-founder of London Video Arts, now LUX, died of complications related to AIDS in London on 31 May 1993. Throughout the 1980s, Marshall’s innovative and, in his own words, “oppositional” AIDS and LGBTQIA+ video and television works were acclaimed internationally.19 These were broadcast and disseminated through exhibitions, film festivals, and activist forums, and Marshall’s archive was subsequently dispersed across the United Kingdom and the rest of Europe and North America. Despite being credited as a cornerstone of transatlantic “AIDS cultural activism” and ongoing revisions in British media history, Marshall’s influential interventions in sound, video, and television remained marginalised and unevenly historicised. They were occluded from dominant critical narratives of US AIDS activist media and UK video art histories well into the 2000s.20

19During the 1980s, Marshall’s videos surfaced through the collective work of London Video Art to promote, distribute, and exhibit video art, reframed by a post-gay-liberationist media activist pitch towards for-and-by LGBTQIA+ television on Channel 4’s series OUT. Marshall’s HIV diagnosis re-catalysed a passionate stake in overlooked queer histories, social justice issues, and AIDS alternative healthcare and self-management. When his partner died suddenly in 2003, Marshall’s archive unexpectedly fell into disarray.21 Shortly thereafter, however, Marshall’s personal papers, which had been held by his TV production company Maya Vision, entered the British Artists’ Film and Video Study Collection at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts, London.

21

Since first encountering Marshall in the LUX collection and the Film and Video Study Collection in the Web 2.0 context of the early 2010s, I have engaged collective archival research efforts among a growing field of Marshall scholars. This connects Marshall’s rich presence in the Canadian archives—namely, his AIDS video work commissioned in Canada—to British and American critical and historical accounts of his work. In April 2024, in the videotape archive of the Ottawa–Gatineau artist-run space SAW, I found Stuart Marshall’s lost video tape of Kaposi’s Sarcoma (A Plague and Its Symptoms) from 1983 (figs. 11 and 12). The recovery of Marshall’s tape occurred during a VIVO Media Arts Centre and Archives Gaies du Québec research placement in Canada.22 This is significant partly because a consensus has emerged in AIDS media scholarship over the last decade that Marshall’s missing tape may be the first AIDS activist video tape in the global AIDS video archive.23

22This short account records collective efforts to reaffirm the significance of Marshall’s Kaposi’s Sarcoma as enduring acts of transtemporal, transgenerational, and transnational LGBTQIA+ and HIV/AIDS solidarity work.

The (Recent) Past: Stuart Marshall on Gayblevision

In 2016 I was invited to lecture on Stuart Marshall at the HIV/AIDS Community Lecture Series at Concordia University, Montreal. This invitation extended my research to Marshall’s Canadian video networks for the first time. Contact with Vtape and VIVO, two of Canada’s leading video organisations, revealed a 1983 broadcast interview with Stuart Marshall from Gayblevision, a Vancouver cable TV show “for gay people by gay people” that had surfaced during recent digitisation.24 In the broadcast, Marshall is touring Canada with Kaposi’s Sarcoma as the official British representative for the 1983 Ottawa International Festival of Video Art. Marshall speaks over a short clip of the video about Kaposi’s Sarcoma and reflects on the early response to AIDS in the United Kingdom—a fragment of a lost work unseen for three decades. The find was thrilling, embodying AIDS video at its inception and prompting hopes for a recovery of the original video tape. In the Gayblevision interview, Marshall explains:

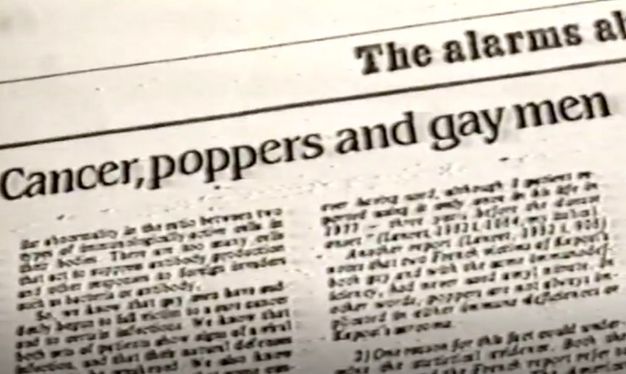

2425The tape is about the way AIDS has been represented by medical journalism in particular, and the dominant media in general. Contemporary medical research is actually destroying a body that the gay liberation movement has built up, that is, an autonomous, proud, homoerotic body, and is reconstructing that body as a pathological and morbid body. A body that shows symptoms of the disease. … As far as I’m concerned, the ways AIDS is represented in the media is nothing more than a form of media queer bashing.25

The Past and Present: 1983 and 2024

It’s 16 April 2024. I am working in the Commons archive of Vtape, Toronto, as part of my doctoral research on Marshall. Vtape, a non-profit founded in 1982, is a leading distributor and preserver of artists’ video in Canada. Next to me is Lisa Steele, feminist video artist, close friend of Marshall, and Vtape co-founder. In an adjoining room, Lisa’s creative and life partner and Vtape co-founder, Kim Tomczak, is carefully cleaning and digitising one of Marshall’s tapes: the hoped-for Kaposi’s Sarcoma, which I have brought here as a loan from the archives of SAW. Between 2016 and 2024, I had followed Marshall’s video activist journey through activist art communities and video networks in Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia, learning more about the tape’s origins and discussing the whereabouts of Kaposi’s Sarcoma with fellow researchers.26 In early 2024 Karen Knights, manager of the VIVO archive, encouraged me to search for Marshall’s lost tape.

26On 2 April 2024 I found the tape among hundreds of chronologically catalogued ¾-inch U-Matic tapes in the SAW archives in Ottawa. Two weeks later, as the recovered tape was digitised, images appeared on-screen in real time of the 1981 Lancet medical journal article “Kaposi’s Sarcoma in Homosexual Men—A Report of Eight Cases”, which along with early articles on “gay cancer” in the British and Canadian gay press, had prompted Marshall’s video and now helped to confirm the tape’s identity.27 The sound was barely audible. A second tape yielded better results—Marshall’s crisp Mancunian accent narrating the bleak prose: “The clinical findings of eight young homosexual men in New York with Kaposi’s Sarcoma showed some unusual features. … The disease was more aggressive, survival of fewer than twenty months rather than eight to thirteen years”.28

27Kaposi’s Sarcoma is named after a cancer, first reported in 1981, as the most visible sign of AIDS-related disease. Marshall’s video, composed in chapters, employs an intertextual approach, making use of found media and medical texts, critical cultural analysis and collaboration with the frontline AIDS clinician Richard Wells.29 Under chroma-keyed titles such as “The Natural” and “The Look”, written in his own hand, Marshall deconstructs the media and medical lens that punitively associates gay men with AIDS. Kaposi’s Sarcoma reflects Cindy Patton’s succinct definition of “homosexuals = AIDS = Death”.30 The video ends with a poignant monologue on what it feels like to live through the early days of AIDS, anticipating the AIDS “structure of feeling” suggested by Gregg Bordowitz.31 The opening scene of medical journal and newspaper headlines is juxtaposed with images of “nature” appropriated from TV documentaries and adverts. Marshall’s campy, playful “consultation” with Wells on the politics of looking is shot inside a busy gay bar with overdubbed conversation and music.

29Marshall: Can you tell me what is the difference between someone catching your eye and someone eyeing your catch?

Wells (laughs out loud) Someone catching my eye is, probably for me, an attraction. It might be somebody passing in the street, or standing next to me in a store, or in a bar. And there’s something about them that immediately draws my gaze towards them … I’m not too sure about someone eyeing my catch!

Through Wells’s eye contact, the camera places the audience within a gay male cruising point of view: the viewer is caught between the look of the cruising glance and the disciplinary gaze of surveillance. This is repeated through scenes that mime a patient undergoing a medical examination, when the televisual rectangle is transformed into the view of a medicalising microscope lens. Marshall’s video method skews the positivist scientific and heterosexist media epistemologies bound up with depicting gay men merely as vectors of AIDS transmission.

The Future: Kaposi’s Sarcoma … Save(d)

Shortly after identifying the tape, I messaged Stuart’s close friend, the film-maker John Greyson, to let him know that Kaposi’s Sarcoma had been recovered. John promptly arranged a screening for the 2024 Viral Interventions Conference at York University, Toronto. Moments later, I was reading a memorial text on Stuart Marshall by his close friend, the Vtape co-founder Colin Campbell (1942–2001), in an email attachment sent by Jon Davies, the Canadian art historian and Campbell scholar. Shortly after his death, Colin, Lisa, Kim and their fellow Vtaper John Greyson opened a computer file for Stuart, in which to keep their memories:

Toronto, June 20, 1993

Last night the four of us, Lisa, Kim, John, and myself, opened a file on my computer called Stuart Marshall.

And into this file we poured four hearts beating in unison.

A kind of medical wonder.

The doctor was sceptical. When he lowered the stethoscope he remarked, “I’ve never heard such a strong syncopated beat.”

“But it’s really very faint,” we replied, “Because one of us is missing.”

Save.

We watched the screen as our words dropped onto the page gradually staining it to all four edges. Wondrous words. All of them were Stuart’s words. His very own because he was unique.

Save.

We ran out of time. We couldn’t believe it. There was no more time and we wanted so much more.

Save.

We wanted to save Stuart collectively and individually. Save him and store him up. We’ll keep this file open.

Marshall’s first AIDS activist video compels us to look back at transnationally oriented, pre-internet art activist spheres of media influence in the United Kingdom that changed the debate on AIDS and LGBTQIA+ sexual representation in the 1980s. The recovery of Kaposi’s Sarcoma enables us to recentre the importance of British media histories of HIV/AIDS cultural activism in the critical counter-narrative of AIDS cultural activism of the long 1980s into the 1990s. This underscores the value of continuity in collective transnational media archival care and solidarity between the United Kingdom and Canada, which Marshall himself helped to establish and which continues today. The recovery of Kaposi’s Sarcoma is one episode in a growing archival activist impetus that continues to recontextualise AIDS histories as forms of community archival care.33

33Contribution by

-

Francesco VentrellaAssociate Professor in Art HistoryUniversity of Sussex

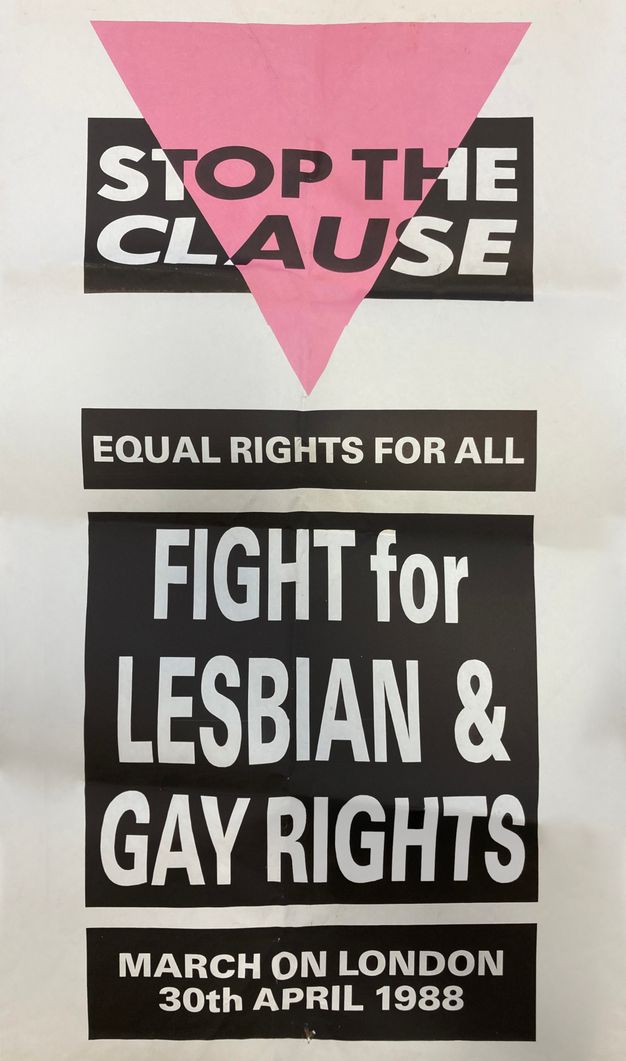

“Stop the Clause” Stickers, 1988

Elizabeth Freeman wrote “that a certain literality, even materiality, glooms onto even the most rigorous deconstruction—that historical details may obstinately stick to or gum up the gears of queer theory”.34 If we theorise queer materials in the archive in relation to experiences that are felt rather than solely recounted, stuck to the body in a “corporealized history”, how do we connect our feelings to the experiences before us?

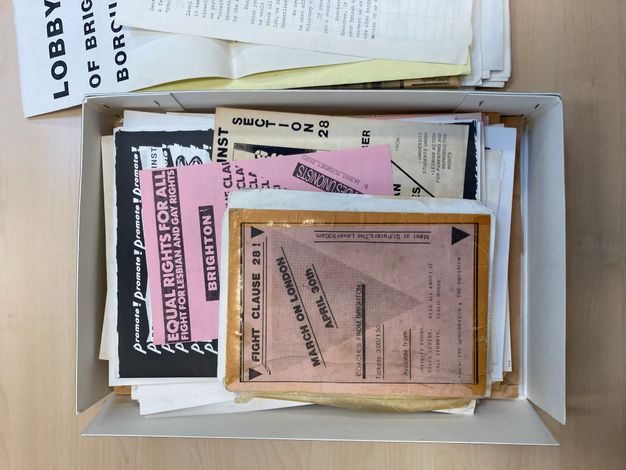

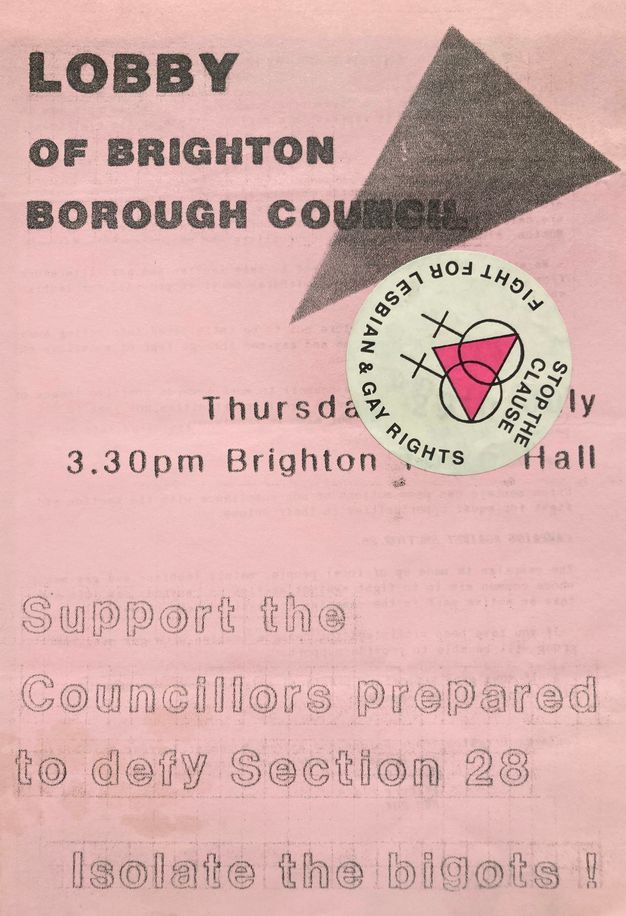

34I open a box in the Brighton Ourstory collection at the Keep Archive Centre in Brighton, West Sussex, and a lot of stuff comes out of it relating to the Brighton Area Action Against Section 28 (fig. 13). I take “stuff” to be another term for material culture because I don’t want—because I don’t really need—to confine within a disciplinary field the feeling of their material promiscuity.35 Founded in 1989 by a group of activists in the community, the Brighton Ourstory project went on for nearly twenty-five years, preserving local lesbian, gay, trans, and bisexual histories, culminating in the creation of a large oral history archive as well.36 Today this collection is used by many queer folk as a means to get closer to regional histories. I would like to use it here to explore the complex, perhaps fuzzy, relation between what archives show and the unseen labour that has gone into creating them.

35

The stuff in the boxes of the Ourstory project is about the lives of its members, the history of the project, Section 28, the city’s famous gay pride, AIDS/HIV, but also parties, travels, magazines, candid photos, friendships, accounts, and just stuff. An archive one can access to find information about queer activism in Britain, these materials do not just serve as documents; rather, their messy assemblage suggests another order, a structure of feelings (to quote Raymond Williams) about a queer use inscribed in their materiality. Recent scholarship on the archive as a site of affective intensity or political agitation has transformed our understanding of such collections from sites of cultural preservation to sites of cultural production.37 Reclaiming an ontology of touch over an epistemology of knowledge, I would like to focus on my encounter with this stuff through texture, sensation, and feeling rather than through seeing or reading alone. I am not interested here in what the stuff in the archive means but in the work it does in a social matrix of queer world-making. To handle stuff from this position involves animating the work of the archives to articulate what remains rhetorically invisible yet is intangibly present.

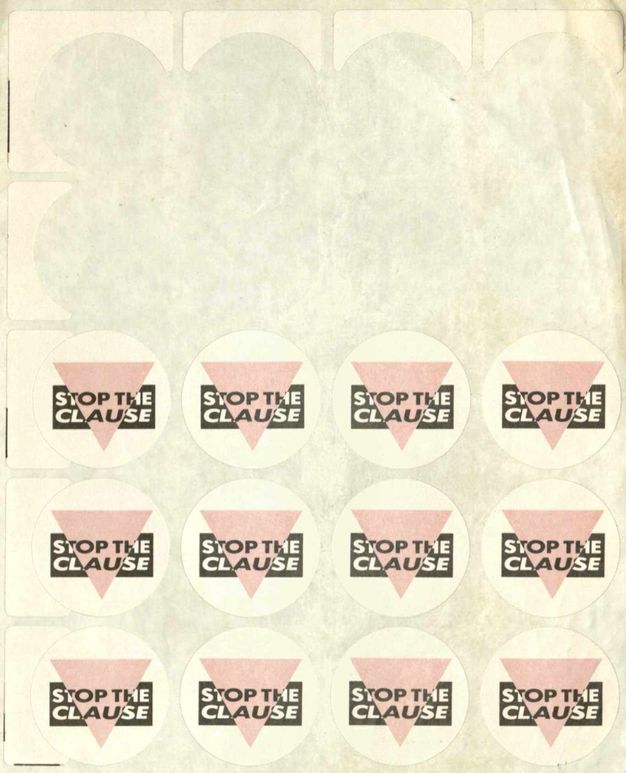

37The archive contains two sheets of “Stop the Clause” stickers printed on pre-cut paper. Many of them are still intact, while the empty patches form an armature where stickers have been peeled off. This sequence of round gaps conveys a sense of how such ephemera moved, and asks us to imagine a connection with the unarchived surfaces onto which the stickers were stuck (fig. 14). As a representational object, the sticker points to a history of activism, but its history remains attached also to its very materiality. Their stickiness feels like a condition of our connection to queer activism in the past, and possibly a move to counter the progress narrative of neoliberal “gay rights”. Mobilising stickiness in the archive does not necessarily mean being stuck in the past, nor does it imply immobility. Rather, to ventriloquise Sara Ahmed, what the sticker “picks up on its surface ‘shows’ where it has traveled and what it has come into contact with”. Its stickiness troubles one’s orientation: it is dynamic and activates movement. Stickiness “could even be described as the transformation of time into form, which itself could be redefined as the ‘direction’ of matter”.38

38

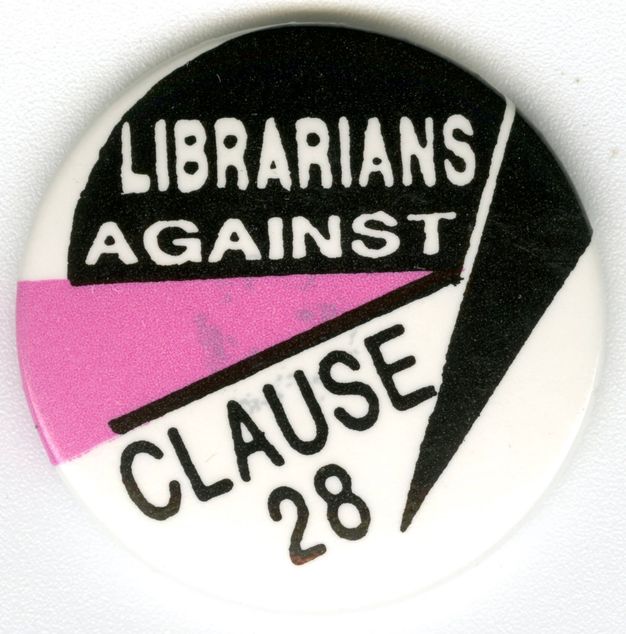

Take the pink triangle printed on these stickers as pointy matter stuck to queer history. The 1986 “Silence=Death” campaign led by ACT UP on the other side of the Atlantic, and the 1988 “Stop the Clause” campaign both used bold capitals and recognisable designs. The pink triangle was employed on a variety of activist stuff, including pin badges, T-shirts, and posters typeset and printed by Calverts Press, the workers’ cooperative founded in 1977 by a group of printers, designers, and typesetters who had been made redundant at their previous employment (fig. 15).39

39

In a recent examination of queer abstraction, Lex Morgan Lancaster turns to the modernist geometry of the triangle as a symbol of convergence and resistance through its transition from badge of shame in the Nazi camps to symbol of self-identification in the 1970s: “Producing a sense of community as well as agitation, the triangle form carries its painful edges and histories of injury while at the same time reinvesting that hardness with possibilities for connection and eroticism”.40 In the 1970s the triangle was also a symbol of lesbian feminism, identified as a grapheme that, beyond anatomical mimesis, polarised in a transitional space ideas and emotions that converged in its political use.41

40While it might look the same, the triangle in another version of the “Stop the Clause” sticker in the Brighton Ourstory archive speaks of a symbolic difference that intersects with lesbian practices of love (fig. 16). The stickiness between these shapes signals an affective capacity about form that, importantly, goes beyond the visual. Ahmed also writes that some objects become sticky “or saturated with affect, as sites of personal and social tension”.42 Sustaining and preserving a connection between ideas and emotions, sticky objects orient us towards the significance of affect for politics.43

42

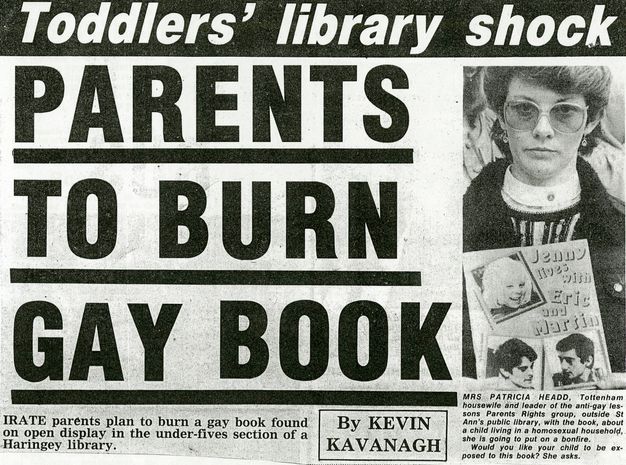

As a symbol of queer memorialisation, the pink triangle pointing downwards was brought into visual culture in the early 1970s after the publication of the memoir of a concentration camp survivor, Heinz Heger.44 The triangle of the “Silence=Death” campaign pointed up instead as a gesture of defiance against its historical origin.45 In its use of the pink triangle pointing downwards, the campaign against Section 28 therefore created an imaginary continuum with the persecution of homosexuality in an age of totalitarianism. The triangle bears a whole series of events sticking to its surface. Disparate objects appear that are glued to a constellation of bad feelings. Headlines about conservative parents threatening to burn “gay books” outside the library in Haringey, a photograph by Sunil Gupta showing a black poster inscribed with pastor Martin Niemöller’s speech “First they came …”, and an armband printed with the word “SILENCED” all use the transhistorical resonance with Nazi Germany to activate a form of public empathy that sticks to the body (figs. 17–19).46

44

Shuffling through the papers in the box, I return to my sticker (see fig. 14). I can feel with my fingers its glossiness contrasting with the grainy surface of the photocopied flyer it partly hides. I wonder what its relation is to the black triangle, with which it forms a strange kind of geometric tangent. The pink flyer calls the community to gather outside Brighton Borough Council, who are meeting on 28 July 1988 to discuss a motion about the non-implementation of Section 28. On the back of the paper, the action group asks councillors not to feel intimidated by the vote in Westminster, and to refuse to “take lesbian and gay literature from library shelves, and not to withdraw services provided for lesbian and gay ratepayers”.47 The law, passed only two months earlier, was infamous for its lack of clarity, which initially created some room for local authorities to assess their role in its application. As many scholars have argued, the legislation of Section 28 marked a moment in the British “culture wars” that brought together two seemingly distant areas of social life, sexuality and local government, under the umbrella of a symbolic discourse about the protection of youth at the time of AIDS.48 The restriction on the “promotion of homosexuality” that was imposed on the autonomy of local government, therefore, was a move in a broader political strategy to demonise the “loony left” in those constituencies characterised as “irrationally obsessed with minority and fringe issues, … paranoid about racial and sexual ‘problems’ which do not exist outside their own fevered imaginings”.49 Undermining the power of local authorities, which oversaw essential services for the community (schools, libraries, children’s clubs), was part of a larger erosion of what the Conservative government saw as a culture of dependency. “There is no such a thing as society”, Margaret Thatcher famously announced.

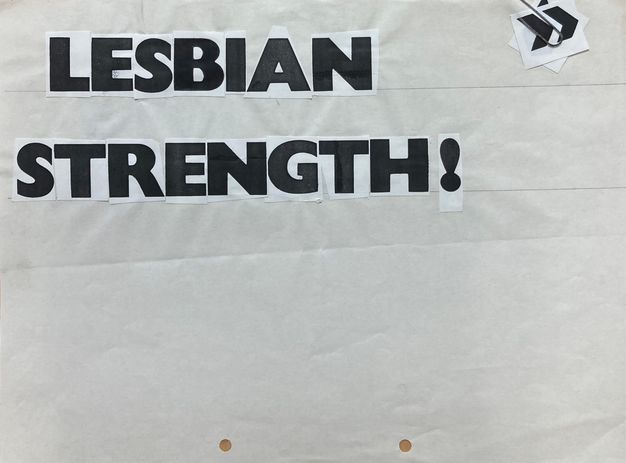

47But this flyer also tells another, parallel, story about technologies of reproduction impressed in the affordability of the photocopy. The bold lettering in the title heading and the block of text at the bottom seem to have been stencilled on graph paper, then cut out and mounted, probably glued or just laid on another sheet, ready to be turned face down on the glass plate of the copy machine. Two flyer mock-ups inside the same box bring out the process of making through a combination of clippings and graphic frames (figs. 20 and 21). They also make tangible activism’s queer connection of photocopies and stickiness. Writing about the use of collage and montage in the artistic practices of the 1980s, Kobena Mercer suggests that they do more than just represent techniques; they are a “cut-and-mix logic” that reorients the debates about identity as a “composite formation made up of decomposable and recomposable elements”.50 This logic is enhanced, in particular, by the creative potential that the photocopier affords the creation of mobile assemblages: queer by design and not only queered by its use in gay and lesbian campaigns of the 1980s. As Kate Eichhorn points out, “with xerography you could simply copy a copy or copy a copy of a copy, and no master copy meant no definitive point of origin”.51 One could make several copies without leaving a trace on the machines they were able to use for free in their workplaces.

50

A brown folder decorated with four different stickers is the unanticipated support for a small catalogue of queer triangles bridging the distance between the spaces of protest and the workplace (fig. 22). Marked as “general” on the spine, the folder, which shows traces of having carried a hefty amount of paper, is now kept empty as an item that, in the hierarchies of the archive, has become equal to the flyers, posters, notes, receipts, and address books it probably contained (fig. 23). As a stationery object, the folder embodies an archival impulse about collating, organising, sorting, ordering, and classifying loose documents. Writing about queer attachments in the archive, Ann Cvetkovich provocatively highlights a fetishistic zeal for materiality, where “even paper documents are important not just for what is written or recorded on them but rather for their paper, binding, and other tactile qualities”.52 This one was produced by HMSO (Her Majesty’s Stationery Office), which was to be privatised in 1996. A relic from an era of publicly funded manufacture, I like to imagine this folder among other things that activism might have borrowed from institutions such as notebooks, staples, and presumably pens. While Section 28 has gone down in history as the law against “the promotion of homosexuality as a pretended family relation”, it also represented a concerted attack on a particular idea of public funding and how it could serve gay, lesbian, and other minoritised communities.

52

Of the four stickers on the brown folder, two replicate the design of the many badges printed by the campaign, including “Librarians against Clause 28” but also teachers, trades unionists, workers, nurses, and more (fig. 24). In these examples, the triangle has changed orientation, which seems to have affected its slant as well.53 No longer pointing down, it has morphed into a wedge reminiscent of Soviet print culture, finding inspiration from El Lissitzky’s famous poster Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1920) (fig. 25). The pink triangle now breaks into the white circle standing for Section 28, and that for Lissitzky represented the White army. I hear echoed the lyrics of Chumbawamba’s “Smash Clause 28!”

53Since the late 1970s, the designer activist David King had been putting back into circulation some of the visual idioms associated with Soviet constructivism from the 1920s. In Lissitzky and Rodchenko King found a visual vocabulary for the Anti-Nazi League (ANL) that answered the racist language disseminated by the National Front through leaflets, posters, and stickers.54 The visual resonance between King’s designs for the ANL and the “Stop the Clause” stickers is a reminder of the concerted efforts among activists of the era to share aesthetic strategies across different interconnected struggles. As Sarah Crook and Charlie Jeffries write, queers in the 1980s were not only responding to painful political developments, “fighting fires as they arose, but also drawing on histories of activism, and imagining and building futures beyond the violence of the present”.55 Indeed, the figure of the “foreign invader” was reused by right-wing media as a blueprint on which to attach a moral panic about the dangerous invasion of lesbians and gay men into local government institutions such as schools, libraries, and community centres.56 Looking at all that stuff in the Brighton Ourstory collection makes me feel that the campaign against Section 28 was much more than a mobilisation for lesbian and gay rights in the 1980s and 1990s: it was also a bundle of feelings about interconnected struggles and strategies. I think we have inherited that stickiness.

54Contribution by

-

James BellLecturer in Contemporary Art TheoryEdinburgh College of Art

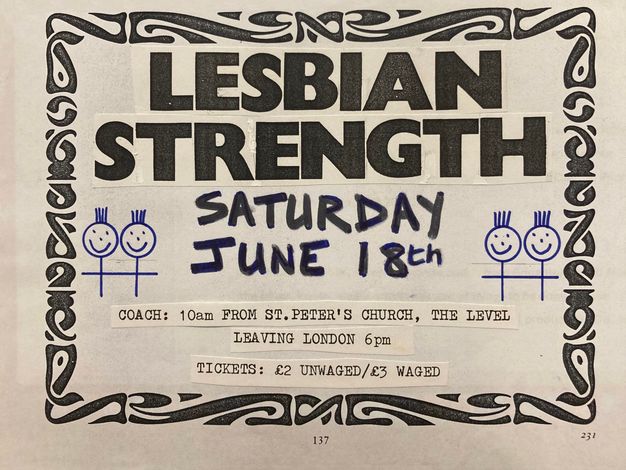

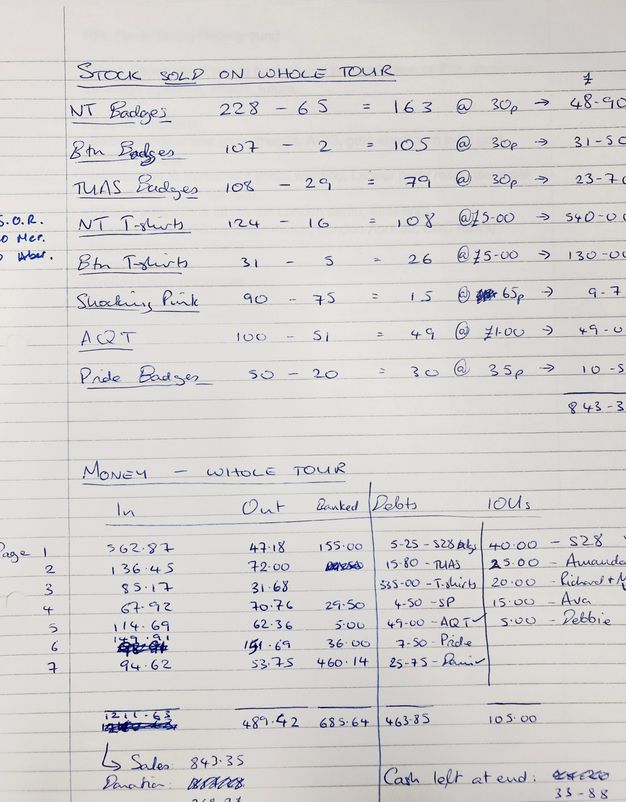

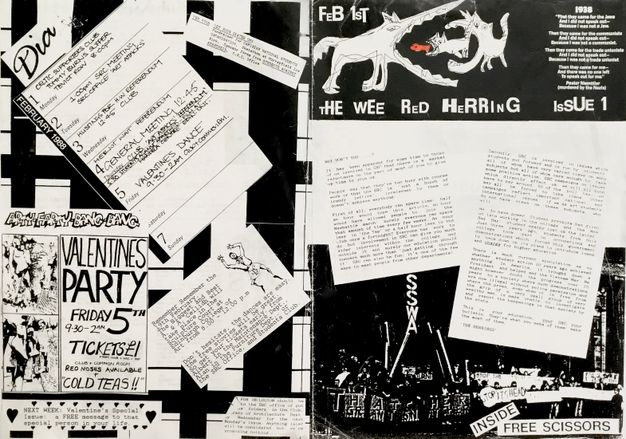

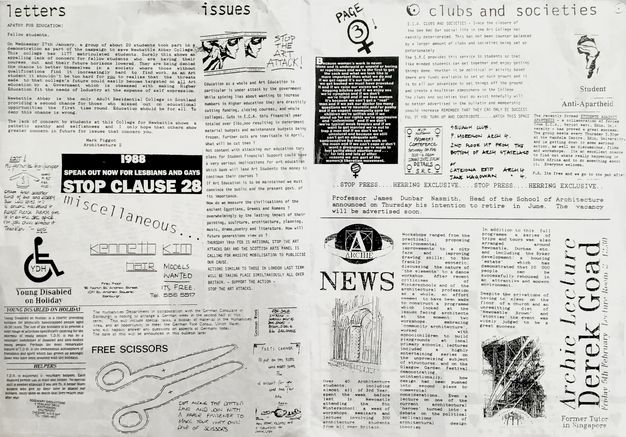

Student Representative Council, The Wee Red Herring 1 (1988)

The Wee Red Herring is a piece of peripheral print that tells a unique story of art and activism at Edinburgh College of Art in the late 1980s (figs. 26a and 26b). Its particularity is both in its geographic position as it reflects on student and queer life in Edinburgh and Scotland, and as a queer archival object that tracks a precarious set of relations then and now. It was published as the bulletin for the college’s elected student body, the student representative council (SRC), in fits and starts from 1988 through the early 1990s until the early 2000s. The first volume of some sixteen and a half issues, dated February to June 1988, are a litmus test for the liveliness of this moment politically in Edinburgh, notably in its coverage of cuts to grants and arts education, and the implementation of Section 28 (called Clause 2A in Scotland), set against a backdrop of the AIDS crisis, which acutely effected the city. What emerges from its pages is an internationalist left politics with a distinctly anarchic art student approach, one that does not neatly align with the mainstream left of student politics in Britain, dominated by the National Union of Students (NUS), nor with Edinburgh’s sizeable gay scene.

As an object, The Wee Red Herring has a do-it-yourself and punk aesthetic that was common in activist, feminist, and queer print cultures in the 1980s. Its normally four to six pages were produced by collaging various written and printed articles, flyers, and other images, cut out and crudely stuck together and photocopied in the SRC office. Its expedient, cheap, and rapid reproduction is a reminder of its function as a bulletin, as Kate Eichhorn argues, for such “communication technologies redefine, expand, and collapse spaces and in the process open up the possibility for new types of networks and communities to take place”.57

57

The Wee Red Herring was started in 1988 by Ronald Binnie with the support of Jane Grey, former SRC president, and Graham Dey, SRC officer, along with the small group of students who made up the SRC and the union’s various societies. Its desire to connect and foster community was always at the fore. In the somewhat antagonistic and provocative first issue featured here, the editorial printed on the first page lamented: “It has been apparent for some time to those of us involved in SRC that there is a marked reluctance on the part of most of you to give up time to join us”.58 This tension between action and apathy is played out in the “Letters” section of the bulletin, one of the few spaces featuring different voices and opinions. Debate, discord, and dissent often follow forms of coming together. The week-by-week publication of the bulletin reflected the immediacy of the dialogue between students on the pressing issues of the time, and provided a space for the messiness of grassroots organising, reflected both in the words of the students who wrote the letters and in the collaged make-up of the bulletin itself.

58The cause that mobilised students most was the “Stop the Arts Attack!” campaign. Originating as a call for solidarity in opposing cuts to arts courses at Loughborough University, it grew into a NUS campaign. Grey and Binnie were the key organisers of an autonomous campaign in Scotland, driven by concerns and politics north of the border. As Binnie reflects: “we decided at that Loughborough conference … there was a need for a national Stop the Arts Attack campaign to challenge not just cuts in arts education, but challenge things like poll tax, things like loans, things like Section 28. All that … was there from the beginning”.59 Edinburgh College of Art was a hub for this organising, and The Wee Red Herring documented it, covering a sit-in at Kelvingrove Art Gallery in Glasgow of over 200 students from art schools in Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Aberdeen.60 Section 28 and its implementation in Scotland also received coverage, from the banner head quotation of Pastor Niemöller calling for solidarity among minority groups in Nazi Germany, taken from a “Stop the Clause” leaflet, to neighbouring Labour-led Strathclyde Regional Council’s heavy-handed implementation of Clause 2A. The Wee Red Herring reflected how art students in Scotland were organising politically, through activities such as the Scottish “Fight the Clause” campaign, based at Glasgow School of Art. The bulletin offered an interconnected account of the many ways in which the Conversative government’s reforms to education and implementation of homophobic policies such as Clause 2A were affecting art students.

59The back cover of The Wee Red Herring was particularly important for this, as it contained a weekly diary recording when and where things were happening, for example a lesbian meeting about “Clause 28 and Lesbian Rights” on Saturday, 13 February, from 2 to 5 p.m. in the basement of the Women’s Centre on 61a Broughton Street. The notice tells us that it has been “organised by lesbians in GALAS (Gay & Lesbian Action Scotland)”. In the same week there was a women’s group meeting in the college for an event called “Women’s Live Artists”, and NUS Scotland’s “Womyns Conference”. During The Wee Red Herring’s first run, a Section 28 benefit was held on 3 March, from 8 p.m. to 2 a.m. Issue 13 shared plans for the Lesbian and Gay Society to attend Lark in the Park, held on 28 May 1988 in Princes Street Gardens, Edinburgh, an important precursor to Pride marches in Scotland, organised by the Scottish Homosexual Action Group (SHAG) and praised in a later issue as an unqualified success. There was a notice about a further benefit for “Stop the Clause” on 10 June at Calton Road Studios, also organised by SHAG, and a series of seminars on sexual politics on the themes of health, opportunities, parenting, and civil liberties in the college. The diary demonstrates the interwoven political and social lives of those active in student politics, and reflects the volume of activism and organising going on at that time in Scotland. I list them here also because the diary enticingly and compellingly points us towards worlds of activity and activism beyond the pages of the bulletin, to spaces where students gathered, organised, and built communities.

The Wee Red Herring occupies a unique position in student, radical left, and queer print cultures in Edinburgh. The different communities, groups, and politics in which the bulletin circulated offers a rich archival contribution to recent research on the histories of student organising in Britain, such as Jodi Burkett’s edited collection Students in Twentieth-Century Britain and Ireland and nascent research on legacies of queer print in Edinburgh, around the Lavender Menace bookshop.61

61As a student publication, the bulletin exists in a discreet history of print at Edinburgh College of Art, its closest precursor being Dynasty, published in 1984 by the SRC. Dynasty was a comic-strip style satire of college management, a parody of the principal and board of governors. Dynasty and latterly The Wee Red Herring provide an insight into the running and politics of the college, which was seen as conservative and traditional in both its governance and its curriculum. Moreover, they created a space for alternative and radical ideas to circulate within the college, particularly among minority groups. The political positioning of The Wee Red Herring is also of note, as it embraced a more anarchic and messy type of politics, reflecting an art school affect and attitude that ran somewhat counter to the more established left- and Labour-aligned politics of the NUS. This is most apparent if one compares The Wee Red Herring to the University of Edinburgh’s student newspaper, The Student, published since 1887, the former a cut-and-paste photocopied zine, the other (at the time) a broadsheet. Indeed, The Wee Red Herring reflects the politics and priorities of college art students as distinct from university student politics, for example, through the coverage of debates on maintenance grants, which were particularly important to working-class students.

The Wee Red Herring also exemplifies the practices of queer print in this period because of its production by predominantly lesbian, gay, and bisexual students and its coverage of pressing issues affecting queer communities in Edinburgh and Scotland. Its left and internationalist politics followed what Fiona Anderson describes as “the growth of a more radical queer community in Edinburgh, affiliated with the political left in the city”, from the early 1980s, connected to the Lavender Menace bookshop.62 The diversity of the gay community in Edinburgh is evident in the anti-identitarian politics of The Wee Red Herring and the queer community around Edinburgh College of Art. In the 1980s the city was at the centre of a burgeoning political consciousness in the wake of the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1981 in Scotland, and by the late 1980s it was at the centre of the AIDS crisis in Europe because of the high infection rate among intravenous drug users. The Wee Red Herring provides a much needed additional peripheral perspective that can decentre the locations and sites from which we write queer histories.

62The movement of The Wee Red Herring into the archives of the University of Edinburgh mirrors the often tense and tenuous relationship between Edinburgh College of Art and the university. The college was absorbed into the university in 2011 at the behest of the Scottish government because it was “financially unsustainable”.63 The foreclosures on arts education that those involved in the bulletin sought to resist, particularly the professionalisation and financialisation of further and higher education, largely came to pass with the Further and Higher Education Act 1992, and continue to play out to this day. The university, the larger and supposedly more stable partner in the 2011 merger, is itself, in early 2025, in a so-called crisis as a result of its embrace of the neoliberal market-driven logics of Thatcher’s reforms.64 The Wee Red Herring stands as a reminder of an earlier moment of queer organising and of the possibilities of resistance in another moment of foreclosure and crisis in higher education in the United Kingdom.

63About the author

-

Fiona Anderson is an art historian based in the Fine Art department at Newcastle University. Her work explores queer art histories from the 1970s to the present, particularly in the context of the ongoing HIV/AIDS epidemic and in relation to preservation and archiving practices. She is the author of the book Cruising the Dead River: David Wojnarowicz and New York’s Ruined Waterfront (University of Chicago Press, 2019), which examines the erotic and political roles that New York’s post-industrial landscape played for various queer communities in the city, and co-editor, with Glyn Davis and Nat Raha, of “Imagining Queer Europe Then and Now”, a special issue of Third Text (January 2021). Fiona’s writing has also been published in journals such as Performance Research, Journal of American Studies, and Oxford Art Journal. She is also a DJ. Her radio show and club night Wildflowers offers a queer feminist and global perspective on country music, folk, and Americana.

Footnotes

-

1

Kate Eichhorn, The Archival Turn in Feminism: Outrage in Order (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2013), 6, 9. ↩︎

-

2

Author’s phone call with Ain Bailey, November 2024. ↩︎

-

3

Author’s video call with Katherine Griffiths, November 2024. ↩︎

-

4

Ingrid Pollard, Postcards Home (London: Autograph, 2004), 10. ↩︎

-

5

Ingrid Pollard in conversation with Radclyffe Hall, November 2024. ↩︎

-

6

Lorna N. Bracewell, Why We Lost the Sex Wars (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021). ↩︎

-

7

Pollard, Postcards Home, 9. ↩︎

-

8

Ingrid Pollard in conversation with Taylor Le Melle, “Club Sauda Panel Discussion”, with Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski, Taylor Le Melle, Zinzi Minott, and Ingrid Pollard, Auto Italia, London, 2 February 2020. ↩︎

-

9

This phrase was frequently printed on the brightly coloured invitation cards produced for each event. A set of these is archived in the rukus! Black, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Trans (BLGBT) cultural archive, aka rukus! Federation Limited, https://search.lma.gov.uk/scripts/mwimain.dll/144/LMA_OPAC/web_detail?SESSIONSEARCH&exp=refd%20LMA/4571. ↩︎

-

10

Ingrid Pollard, “Club Sauda Panel Discussion”. ↩︎

-

11

Hot Moment, Auto Italia, London, 11 January–14 March 2020, group show; Hasselblad Award 2024: Ingrid Pollard, Hasselblad Foundation, Gothenburg, 12 October 2024–19 January 2025, solo show; The 80s: Photographing Britain, Tate Britain, London, 21 November 2024–5 May 2025, group show. ↩︎

-

12

Ingrid Pollard, “Home and Away: Home, Migrancy, and Belonging through Landscape Photographic Practice” (PhD thesis, University of Westminster, 2016), 61. ↩︎

-

13

This grassroots working together is something that Pollard’s lens was attuned to. Her images of Black women working together appear in the “Many Voices, One Chant: Black Feminist Perspectives” issue of Feminist Review 17, no. 1 (1984), and in Maud Sulter, ed., Passion: Discourses on Blackwomen’s Creativity (Hebden Bridge: Urban Fox Press, 1990). ↩︎

-

14

“Contributors”, Feminist Review 17, no. 1 (1984): 118. ↩︎

-

15

A Candid Conversation with Audre Lorde (London: Late Start Collective, 1985), film held by Cinenova. ↩︎

-

16

“Black Woman Talk: Black Woman Talk Collective”, Feminist Review 17, no. 1 (1984): 100. ↩︎

-

17

Minutes of Feminist Review collective meeting, 3 June 1984, MCINTOSH/10/16, The Women’s Library, London School of Economics and Political Science, London. ↩︎

-

18

Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Survival Is a Promise: The Eternal Life of Audre Lorde (London: Allen Lane, 2024), 294. ↩︎

-

19

Stuart Marshall, “Video: From Art to Independence”, Screen 26, no. 2 (March–April 1985): 69–70. Marshall’s Journal of the Plague Year (after Daniel Defoe) and Bright Eyes, both from 1984, are canonical works in the AIDS cultural activist archive. See Douglas Crimp, ed., AIDS: Cultural Analysis / Cultural Activism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1988), and Alexandra Juhasz, AIDS TV: Identity, Community, and Alternative Video (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995). His TV documentaries Desire (1989), Comrades in Arms (1990), Over Our Dead Bodies (1991), and Blue Boys (1992) received widespread press coverage and have been anthologised in collections including Tessa Boffin and Sunil Gupta, eds., Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology (London: Rivers Oram Press, 1991), and Martha Gever, Pratibha Parmar, and John Greyson, eds., Queer Looks: Perspectives on Lesbian and Gay Film (New York: Routledge, 1993). ↩︎

-

20

Douglas Crimp, “AIDS: Cultural Analysis / Cultural Activism”, October 43 (Winter 1987–88): 3–16. ↩︎

-

21

Rebecca Dobbs, interviewed by author, 2016. ↩︎

-

22

This research was funded by AHRC / Northern Bridge Consortium and Northumbria University as part of a collaborative doctoral research project between Northumbria University and LUX titled “Learning in a Fantastically Public Medium: Stuart Marshall and Sound, Video and Television as Art and Activist Media, 1968–1993”. ↩︎

-

23

See Ed Webb-Ingall, “Do Not Tape Over: AIDS Activist Videos in the United Kingdom”, in this issue of British Art Studies and Video Activism Before the Internet: 1969–1993, Paul Mellon Centre, Postdoctoral Fellowship, video, 3:52 mins., https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk/grants-and-fellowships/video-activism; Tommaso Speretta, “What Did AIDS Do to Handsome Kenny’s Eyes?”, in From the Logic of the Lure to the Force of the Erotic: Cruising a Personal AIDS Video Archive from a Curatorial Perspective (Zurich: On Curating, 2024), 76–84, https://www.on-curating.org/files/oc/dateiverwaltung/books/Tommaso%20Speretta/phd_tommaso_speretta_web.pdf. ↩︎

-

24

I would like to credit the unwavering support of Professor Thomas Waugh and Ryan Conrad in their initial support for my archival work in Canada. For Gayblevision (1980–86), see VIVO Archive, https://archive.vivomediaarts.com/gayblevisions/. ↩︎

-

25

Stuart Marshall interviewed by Gayblevision, “Gay T.V. in England”, episode 37, aired 4 and 18 July 1983, 29:49, Gayblevision Fonds, Christa Dahl Media Library & Archive, VIVO Media Arts Centre, https://vimeo.com/groups/461954/videos/163477144. ↩︎

-

26

Conal McStravick, “Recontextualiser la contribution montréalaise et internationale du documentariste et militant britannique Stuart Marshall en tant que militant pour les droits LGBTQ2S+”, L’Archigai 34 (2024): 6, https://agq.qc.ca/documents/archigai/Archigai_no34_2024.pdf. ↩︎

-

27

K. B. Hymes et al., “Kaposi’s Sarcoma in Homosexual Men—A Report of Eight Cases”, Lancet, 2, no. 8247 (19 September 1981): 598–600. See B. Lewis and R. Coates, “‘Gay’ Cancer or Mass Media Scare?”, Gay News 228 (12 November 1981): 21, and Michael Lynch, “Living with Kaposi’s Sarcoma and AIDS”, Body Politic 88 (November 1982): 31–37. ↩︎

-

28

Stuart Marshall, dir., Kaposi’s Sarcoma (A Plague and Its Symptoms), Vtape and LUX, 1983, video, 25 minutes. ↩︎

-

29

John Atkinson, “Obituary: Richard J. Wells”, Independent, 9 January 1993, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-richard-j-wells-1477518.html. ↩︎

-

30

Cindy Patton, Sex and Germs: The Politics of AIDS (Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1986). ↩︎

-

31

Gregg Bordowitz, “The AIDS Crisis Is Ridiculous”, in Queer Looks: Perspectives on Lesbian and Gay Film and Video, ed. Martha Gever, Pratibha Parmar, and John Greyson (New York: Routledge, 1993), 209–24. ↩︎

-

32

Colin Campbell, unpublished text on Stuart Marshall, 1993. Courtesy of the Estate of Colin Campbell / Vtape and Jon Davies. ↩︎

-

33

Howard Zinn, “Secrecy, Archives, and the Public Interest”, Midwestern Archivist 2, no. 2 (1977): 14–26; Marika Cifor, Viral Cultures: Activist Archiving in the Age of AIDS (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2022). ↩︎

-

34

Elizabeth Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 112. ↩︎

-

35

Daniel Miller, Stuff (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2010). ↩︎

-

36

See https://www.brightonourstory.co.uk. On the oral history project see also Alison Oram, “Making Place and Community: Contrasting Lesbian and Gay, Feminist and Queer Oral History Projects in Brighton and Leeds”, Oral History Review 49, no. 2 (2022): 227–50. While the Ourstory archive is overall inclusive of local LGBTQI+ narratives, the materials in my box reflect the historic invisibility of trans and intersex activism in the campaign against Section 28. On this issue see Del LaGrace Volcano in Virginia Preston, ed., Section 28 and the Revival of Gay, Lesbian and Queer Politics in Britain, ICBH Witness Seminar Programme (London: Institute of Contemporary British History, 2001), 41, and Juliet Jacques, "Protest Guest Blog: 'The Stop the Clause March, Thirty Years On", Comma Press Blog, 12 February 2018, https://thecommapressblog.wordpress.com/2018/02/12/protest-guest-blog-the-stop-the-clause-march-thirty-years-on-by-juliet-jacques/. ↩︎

-

37

See, e.g., José Esteban Muñoz, “Ephemera as Evidence: Introductory Notes to Queer Acts”, Women and Performance 8, no. 2 (1996): 5–15; Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003); Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017); Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2019). ↩︎

-

38

Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 40. ↩︎

-

39

See Jenny Thornley, Workers’ Cooperatives: Jobs and Dreams (London: Heinemann Educational, 1981). ↩︎

-

40

Lex Morgan Lancaster, Dragging Away: Queer Abstraction in Contemporary Art (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 56. ↩︎

-

41

Griselda Pollock, Encounters in a Virtual Feminist Museum (London: Routledge, 2007), 51–54. ↩︎

-

42

Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 2nd ed. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014), 11. ↩︎

-

43

Sara Ahmed, “Happy Objects”, in The Affect Theory Reader, ed. Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), 29. ↩︎

-

44

Heinz Heger, The Men with the Pink Triangle, 2nd ed. (Chicago: Haymarket Books, [1972] 2023). ↩︎

-

45

For a discussion of ACT UP’s design and print strategies, see Kate Eichhorn, Adjusted Margins: Xerography, Art and Activism in the Late Twentieth Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), 121–28. ↩︎

-

46

For a discussion of how the Holocaust is often mobilised across intersectional protests, and of the limits of this mobilisation, see Michael Rothberg, The Implicated Subject: Beyond Victims and Perpetrators (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019). ↩︎

-

47

“Lobby of Brighton Borough Council”, flyer, OUR/ACC11645/123/1, The Keep, Brighton. ↩︎

-

48

Anna Marie Smith, New Right Discourse on Race and Sexuality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994). ↩︎

-

49

Julian Petley, “Not Funny but Sick: Urban Myths”, in James Curran, Julian Petley, and Ivor Gaber, Culture Wars: The Media and the British Left, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2018), 59. See also Smith, New Right Discourse, 17. ↩︎

-

50

Kobena Mercer, “The Longest Journey: Black Diaspora Artists in Britain”, in “Rethinking British Art: Black Artists and Modernism”, ed. Sonia Boyce and Dorothy Price, special issue, Art History 44, no. 3 (2021): 485, 503. ↩︎

-

51

Eichhorn, Adjusted Margins, 115. ↩︎

-

52

Ann Cvetkovich, “Photographing Objects as Queer Archival Practice”, in Feeling Photography, ed. Elspeth H. Brown and Thy Phu (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), 275. ↩︎

-

53

Stef Dickers, “Badge-tastic Section 28 special!”, Twitter, 24 May 2018, https://x.com/stefdickers/status/999734193415446528. ↩︎

-

54

Elizabeth Robles, “Collage and Recollection in the 1970s and 1980s: Three Black British Artists”, Wasafiri 34, no. 4 (2019), 57. See also Rick Poynor, David King: Designer, Activist, Visual Historian (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020). ↩︎

-

55

Sarah Crook and Charlie Jeffries, eds., Resist, Organize, Build: Feminist and Queer Activism in Britain and the United States during the Long 1980s (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2022), 3. ↩︎

-

56

Smith, New Right Discourse, 196–204. ↩︎

-

57

Kate Eichhorn, Adjusted Margin: Xerography, Art, and Activism in the Late Twentieth Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), 2. ↩︎

-

58

“Why Don"t You …?”, Wee Red Herring 1, no. 1 (1 February 1988): 1. ↩︎

-

59

Ronald Binnie, interviewed by author, 26 March 2024. ↩︎

-

60

“Art Attacks … What the Papers Said …”, Wee Red Herring 1, no. 4 (22 February 1988). ↩︎

-

61

Jodi Burkett, ed., Students in Twentieth-Century Britain and Ireland (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018); Fiona Anderson, “Revisiting Lavender Menace: In Conversation with Sigrid Nielsen, Bob Orr and James Ley”, in Queer Print in Europe, ed. Glyn Davis and Laura Guy (London: Bloomsbury, 2022), 237–58, DOI:10.5040/9781350158696. ↩︎

-

62

Anderson, “Revisiting Lavender Menace”. ↩︎

-

63

“Art College Hits Back in Row over Financial Management”, Scotsman, 24 January 2011, https://www.scotsman.com/news/art-college-hits-back-in-row-over-financial-management-1687674. ↩︎

-

64

Laura Paterson, “Edinburgh University to Cut Staff to Plug £140 Million Black Hole”, Herald, 26 February 2025, https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/24964505.edinburgh-university-cut-staff-plug-140-million-black-hole/.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 14 July 2025 |

| Category | One Object |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Editorial Group) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-27/oneobject |

| Cite as | Anderson, Fiona. “The Practice and Politics of Archival Labour in Histories of Queer Art in Britain.” In British Art Studies: Queer Art in Britain since the 1980s (Edited by Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, Theo Gordon and Laura Guy), by Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, Theo Gordon, and Laura Guy. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-27/oneobject. |