Living Proof

Living Proof: Tracing HIV/AIDS Cultural Production in the North East of England

By Fiona Anderson

Abstract

This article traces a history of Living Proof (1991–92), a collaborative, multidisciplinary arts project produced with diverse communities living with HIV/AIDS across the North East of England. The workshops, exhibitions, and performances produced as part of—and in response to—Living Proof engaged directly with racialised and gendered experiences in the United Kingdom of HIV/AIDS care, addiction, the prison system, and the radical power of international solidarity with AIDS activists and cultural producers in North America, including Pomo Afro Homos and the so-called NEA Four. The history of Living Proof speaks to the distinctive funding, galleries, and festival and community networks in the region in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It is an overlooked but vital part of UK AIDS histories. This article draws on the project’s scattered archive and conversations with those involved, to think critically about what it means to historicise it now, in the midst of an archival turn in HIV/AIDS scholarship, as British art that responded to art and HIV/AIDS in the 1980s and after receives greater scholarly attention, and while health and economic inequalities in the region persist.

Introduction

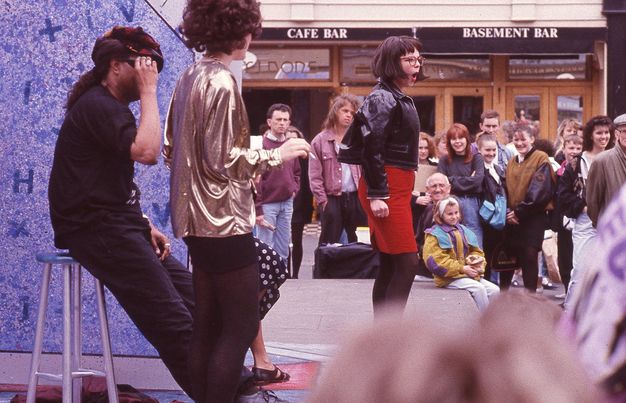

On a Friday afternoon in May 1992, a crowd gathered around Grey’s Monument in Newcastle upon Tyne to watch a performance called The Last Blind Date Show. The monument is a grand Doric stone column with a wide elevated base that recognises the political work of the former British prime minister Charles Grey, particularly the passing of the Great Reform Act in 1832. It stands at the centre of a busy intersection in the city’s main shopping area and has long acted as a meeting place for rallies, protests, and vigils. It is one of the city centre’s most public and recognisable historic landmarks. Photographic documentation of The Last Blind Date Show shows the crowd clustered around two sides of the monument (fig. 1]. It captures a handful of passers-by with quizzical, perhaps sceptical, expressions, most of whom are older and smartly dressed, as they walk around the edge of the audience, who seem fairly diverse in terms of age, with young people in bright shell-suit bomber jackets and jeans sharing space with older people in grey and navy suits. Most of them appear to be white, unlike the performers, half of whom are Black. The photograph also shows a colourful set installed at the foot of the monument, divided like that of Blind Date, the ITV game show the performance sends up, by a distinctive partition separating the contestant from their three potential dates. The set is painted in blue and pink, with the letters and symbols that make up the acronyms HIV+ and AIDS scattered across it, behind the assembled singles and their animated host, “Venus Decomposing, or Venus for short”. The Last Blind Date Show, Venus tells her motley bunch of viewers, is “the show with a difference, the thinking person’s show, the show with all the questions but no answers. It will make you laugh, cry, angry, happy”.1

1

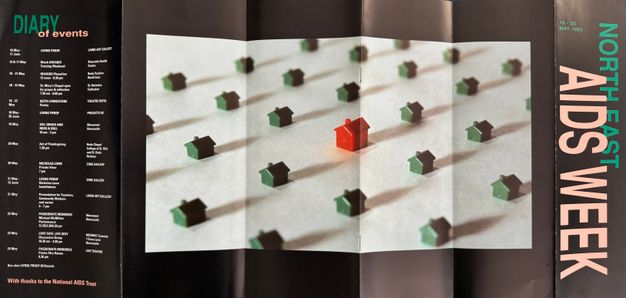

The Last Blind Date Show was developed by the London-based playwright, artist, and educator Michael McMillan. It was performed as part of North East AIDS Week, one of the culminating events of what became known as Living Proof (1991–92), a year-long community arts project exploring the impact of HIV/AIDS on diverse constituencies across the North East of England, led by the organisation Artists’ Agency (now known as Helix Arts), which then had its offices in Sunderland (fig. 2). McMillan was the project’s writer-in-residence and the multidisciplinary artist and curator Nicholas Lowe was artist-in-residence. In “discussion-based” workshops, McMillan worked with amateur performers and writers “infected and affected by HIV/AIDS” to produce a script that explored with comedic directness their experiences of dating while HIV-positive, desire, homophobia, legacies of colonialism and racialised stigma towards people living with HIV, and the impact of racist misinformation on public awareness of HIV/AIDS in Britain (fig. 3).2 The performance did so in a Brechtian format designed to grab the attention of passers-by, from the student standing by the monument playing the Blind Date theme song on a saxophone and the bright colours of the set to the script’s explicit references to HIV/AIDS and use of frank and informal language to speak about desire, racism, and fear. “We had an audience”, McMillan told me, “almost demanded it. We had grabbed people and [we] made sure that they, doing their shopping on a Saturday, … they were gonna notice us”.3

2

The frankness of The Last Blind Date Show, the complex and interconnected subjects it explored, and the central role played by amateur performers and writers in its development and performance mirror the approach of the Living Proof project as a whole. The workshops, exhibitions, and performances produced in collaboration with McMillan and Lowe as part of Living Proof and in response to it by galleries and other arts organisations in the region engaged directly with racialised and gendered experiences of HIV/AIDS in Britain, haemophilia, addiction and substance use, and the prison system. It had a distinctively North East identity, primarily through its engagement with local HIV service organisations, nightclubs, churches, and community groups across the region, and through its focus on conversation with people living in the region who were impacted by HIV/AIDS. Some of the interviews collected by Lowe during the project’s run were published as part of a book, also called Living Proof, that presented participants’ photographs and creative writing alongside reflective texts by Lowe, McMillan, and Esther Salamon.4 These conversations capture the distinctive openness of Geordie culture and evidence its status as, in the words of Bill Lancaster, a leading historian of the region, both “one of Britain’s best examples of urban sociability” and “the forgotten corner of a British nation state … both too big and too small for the job it has to do”.5 They relay the challenges of living with HIV and AIDS in the North East of England in the early 1990s and of working in the healthcare sector at this time, particularly as these experiences intersected with racism and regional socio-economic deprivation.

4Crucially, Living Proof also looked outwards to “a world living with HIV and AIDS” (fig. 4).6 Drawing on a rich regional network of arts venues and festivals that provided specialist support and funding for live art and performance in the 1980s and early 1990s, the project explored the radical potential of international solidarity with AIDS activists, artists, writers, and performers in North America. This included supporting the staging of a work by the theatrical performance troupe Pomo Afro Homos (founded in San Francisco in 1990 by Djola Bernard Branner, Brian Freeman, and Eric Gupton, who were later joined by Marvin K. White) at Newcastle’s Live Theatre and, through the Newcastle-based arts organisation Projects UK, performances by the artists Annie Sprinkle, Karen Finley, Tim Miller, and Holly Hughes, who had all endured censorship in the United States through the vetoing of proposed grants from the US National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) by its chair, John Frohnmayer. This stemmed from a reduction of the NEA budget under Ronald Reagan’s presidency and growing interest in NEA spending from conservative lawmakers, including Senator Jesse Helms, which led to the cancellation of an exhibition of work by the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, in 1989.7

6

Inviting the NEA Four to Newcastle was a gesture of friendship that acknowledged shared experiences of right-wing media attention and censorship in the 1980s and early 1990s, particularly of cultural production related to sex and sexuality, with a view to working collaboratively and empathetically to develop strategies for dealing with a repressive funding landscape. Living Proof took place while local-authority-funded arts projects and exhibitions in the United Kingdom that addressed lesbian and gay life, including HIV/AIDS, faced pre-emptive censorship and the threat of prosecution under Section 28 of the Local Government Act, which prohibited the “promoting [of] homosexuality”. One of the most striking aspects of how Living Proof was conceptualised and framed is that its component parts were developed in this restrictive British political context without self-censorship or censure from the multiple organisations and various funders involved. Lowe suggested later that Living Proof was possible in this conservative national cultural climate “because nobody was looking” at what artists and community arts organisations were doing so far north, though in 1990 a planned exhibition of the group show Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology in Salford in the north-west of England was cancelled in fear of Section 28, as I shall explore later in this article.

In 1992 Esther Salamon, then co-director of Artists’ Agency and the driving force behind Living Proof, stated that the intention of the project was “to raise the wide-ranging and complex issues surrounding HIV and AIDS and bring them to as wide an audience as possible”. Living Proof, she wrote, was designed “to enable individuals directly affected by HIV and AIDS to creatively express their concerns, interests, hopes, and fears”.8 But she was also committed to ensuring that McMillan and Lowe had the time and support “to pursue work of their own which promoted new understanding and interpretations of the issues by creating imagery, metaphors and perspectives which confronted the various aspects surrounding the infection”, some of which was exhibited at local arts venues such as the Laing Art Gallery and Zone Gallery. “The rest”, she said, “is history”.9 Yet today the project is little known, even within the North East of England and, like many regional community arts projects, its archive is minimal. Much of the work produced as part of McMillan and Lowe’s residencies and inspired by it was time-bound or intentionally ephemeral, shared as part of one-off performances, small exhibitions, or workshops in 1991 and 1992, and much of it was made by participants who did not work or identify as artists.

8Living Proof is an overlooked but vital part of British HIV/AIDS histories and histories of HIV/AIDS-related cultural production in the United Kingdom. In looking to shed light on this regional history, I draw on Jih-Fe Cheng, Alexandra Juhasz, and Nishant Shahani’s important edited collection AIDS and the Distribution of Crises (2020), which approaches AIDS “as an ongoing, global crisis—experienced locally and with specificity”,10 and echo Viviane Namaste when she asks:

1011How do we tell the history of AIDS, locally and globally? What frameworks are privileged in our understandings of the epidemic, and how do these shape our responses in the current moment? What might be the benefit of rethinking conventional histories of HIV/AIDS at both scholarly and political levels?11

For Namaste, this is in part a question of which accounts of HIV/AIDS have come to the fore and which have been sidelined, both in the past and in the present. She argues for the importance of looking beyond well-historicised and “recognized sites of AIDS activism”, such as the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), towards local examples of community organising (in her case, Haitian communities in Montreal), to prevent a flattening “of the complexity of AIDS activism”.12 Like Namaste, I am undertaking this work at an archival turn in HIV/AIDS scholarship, exemplified by recent publications about AIDS and archives in North America by scholars such as Robb Hernández and Marika Cifor, and in the UK context by George Severs, whose book Radical Acts: HIV/AIDS Activism in Late Twentieth-Century England draws on a wide range of archival media and oral history interviews to explore everyday activism beyond ACT UP London.13 Cifor argues that “archives are becoming as important to understanding AIDS as the biomedical event of HIV/AIDS itself” and that “archiving, the practices and acts of creating, collecting, preserving, and making accessible political, cultural, and medical knowledge, is a vital component of what Douglas Crimp terms ‘AIDS cultural activism’” because it allows for new and more diverse understandings of the epidemic to emerge and for previously overlooked accounts to be made visible.14 Informed by this archival turn and by the emphasis Cifor places on the powerful potential of archives to expand public understanding of HIV/AIDS, I trace in this article a history of Living Proof, drawing on its scattered archive and on conversations with those involved, and consider what it might mean to historicise it now, as British art that responded to art and HIV/AIDS in the 1980s and after receives greater scholarly attention (including in other contributions to this special issue) and as stark regional socio-economic and health disparities in the United Kingdom persist.

12Community Arts and the AIDS Mythology

Living Proof was initiated in 1988 by Esther Salamon in her capacity as co-director of Artists’ Agency, a year after she joined the organisation. Artists’ Agency was founded by Lucy Fairley in Sunderland in 1983 with the aim of facilitating “transdisciplinary artistic interventions that addressed social and environmental problems” by “connecting high quality artists with diverse and disadvantaged communities to make great art together in northern towns as a way of amplifying the voices of those who were seldom heard”.15 It gained charitable status in 1989. Although the region was struggling economically, the late 1980s and early 1990s were a period of lively cultural activity in the North East of England, particularly Newcastle. At the turn of the 1980s, as Gabriel Gee has noted, as the effects of deindustrialisation took hold, “there emerged … a notable trend of self-led artistic initiatives that took advantage of urban spatial availability. Studios and art collectives grew in the interstices of structural decay”, making use of vacant warehouses around the Ouseburn Valley and the quayside along the Tyne, as well as empty retail and office space in the city centre.16 This period also saw the establishment of several important Newcastle-based arts organisations, including Live Theatre and Projects UK, the latter of which had also been founded in 1983, and international arts festivals such as the Tyne International, which began in 1990. Each actively supported experimental performance, live art, public art, and cultural engagement in the city.

15In the summer of 1990, the Gateshead Garden Festival, the fourth of five national garden festivals and “one of the largest sculpture exhibitions ever held in Britain”, brought over seventy installations to “a 200-acre slice of reclaimed industrial wasteland” along the Tyne in Dunston.17 “The model of the Garden Festival”, Gee notes, “came from Germany, where it had been introduced as a tool of economic reconstruction initially of bomb-damaged areas and later of disused industrial sites”.18 However, as Paul Usherwood argued in Art Monthly, media photographs of the event “seldom conveyed any sense of the brighter, cleaner future which the Festival as a whole was meant to portend”, highlighting instead “the one remaining relic of the area’s industrial past, a huge wooden coal staithe running down to the river”.19 Throughout the 1990s, the Tyne and Wear Development Corporation (TWDC), which was established in 1987, supported several regeneration-minded arts projects in public spaces in the region, joining other development corporations nationally in “responding to the Arts Council initiative promoting ‘percentage for art’ legislation which stipulated that a proportion of budgets for new construction should be set aside for decorative purposes”.20 In the North East of England this included the commissioning of sculptures exploring themes relating to the lost industry of shipbuilding and the keelmen who worked along the quayside until the later nineteenth century, as part of the “culture-led” regeneration of the area led by the architectural firm Terry Farrell & Partners.21

17Artists’ Agency tended to work apart from this funding model and eschewed corporate collaborations and commissions. In 1989, for example, it began developing ideas for a sculpture trail on St Peter’s Riverside in Sunderland, another once industrial area that was being redeveloped by the TWDC. Malcolm Miles noted that, “rather than approach the TWDC and private sector developers as patrons of conventional public art, the [Artists’] Agency began by bringing together a group of local people and community groups, schools and churches”, which led to their commissioning a long-term artist residency.22 Responding to conversations with these local stakeholders, the resident artist Colin Wilbourne created “sculptures carved from the sandstone remaining from demolition of previous buildings, to lend ‘visual cohesion’ to the site” without referring directly to the stark loss of industry, “rather as if it might be still a private grief”.23 For Miles, this approach represented “not a colonisation of local history” by a culturally minded development corporation, but “the accountability of the artist to a representative group of local people”, facilitated by a local community arts organisation.24 He described Artists’ Agency’s method as “a model of community involvement which declines to offer corporate baubles or controlling utopias”.25 Some of these sculptures are still in situ today.

22Esther Salamon began work on what would become Living Proof using a similar method. Beginning in 1988, she met with representatives of local HIV/AIDS support organisations and healthcare providers including the Newcastle Haemophilia Centre, Body Positive North East, Newcastle General Hospital, and regional charities providing alcohol and drug addiction support. They all “agreed that something needed to be done” to respond to the HIV/AIDS crisis in the region and the limitations of existing representations of people with AIDS in the mainstream press and public health campaigns.26 The aim was not to produce new educational materials but to challenge dominant media narratives about HIV transmission and risk, and the fearmongering and individualistic rhetoric of national campaigns such as “AIDS: Don’t Die of Ignorance” and “AIDS: You’re as Safe as You Want to Be”, launched by the UK Health Education Authority in 1986 and 1988 respectively. As Simon Watney argued in 1989, “the epidemic has been used to articulate values and beliefs that have nothing to do with AIDS. In effect, health education has been recruited to the prior purpose of political and ideological struggle”.27

26Alluding in part to the repressive effects of Section 28 and to politicised resistance to “the long-established fact of heterosexual transmission” in the United Kingdom, Watney noted in the same essay that

28for such purposes it has seemed far more important to establish the idea that homosexuality is an intrinsic wrong, than to communicate the relatively simple information that explains how and why different people are at different degrees of risk from HIV.28

In her foreword to the book Living Proof, Salamon similarly observed that “AIDS is one of those issues whose media representation reveals more about society’s prejudices than it does about the epidemic, its immediate symptoms or social context”.29 She recalled that, in these meetings in 1988, representatives of local HIV/AIDS support organisations agreed “that there was an urgent need to move beyond the two dimensional views being offered by the media” and “create imagery which confronted the social and cultural issues surrounding the epidemic”, reflecting its complexity in empathetic and nuanced ways.30 Artists, Salamon argued, “can play a vital role in this process”.31 Salamon’s nuanced approach to HIV/AIDS-related cultural production echoed that of the photographers Tessa Boffin and Sunil Gupta, who developed the exhibition and book Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology between 1988 and 1990 to address “the way AIDS had been represented in the media”, “particularly the British media’s savage attack on people with AIDS”, and to consider “the politics of representation” in relation to HIV/AIDS rather than “the representation of politics” in a didactic sense.32

29In dialogue with the partner organisations and stakeholders, it was agreed that artist residencies over a year-long period would enable the artists developing workshops and their own creative practice to embed themselves within the region and develop genuine connections with the various communities they would be working with, as well as to acquire an understanding of the regional arts infrastructure. What the historian Robert Colls called the North East’s “strong regional coherence”, which stems in part from its rich industrial heritage and its physical distance from London and other major English cities, underpinned Salamon’s approach to the development of Living Proof, enabling Lowe and McMillan to build strong connections with the diverse communities impacted by HIV and AIDS and develop regionally appropriate modes of working.33 The decision to have two residencies over almost a year, one focused on photography and the other on creative writing, was informed by “questionnaires [which] were produced and distributed to people affected by HIV and AIDS in the North East”, who “in equal numbers—expressed a preference for photography and creative writing”.34 Though it was developed in dialogue with several local healthcare providers, the project was emphatically “not art therapy” because, Salamon told me in 2023, that would be clinically related and, as such, outside the remit of a community arts organisation.35

33Salamon’s vision for the two residencies resonates instead with Petra Küpper’s definition of community performance: “work that facilitates creative expression of a diverse group of people, for aims of self-expression and political change”.36 Doing this at a local level meant that the project could respond to the particularities of living with HIV and AIDS in the North East of England (which in the late 1980s had the worst health inequalities in the country, fuelled by “high levels of unemployment [and] changes in tax and state benefits systems” across the decade37), developing a range of targeted delivery methods that addressed the specific experiences, needs, and cultural vocabulary of its participants, from young men in prison to men and women from the region’s South Asian communities, some of whom tended to see “HIV and AIDS as a white disease”.38 In 1988, as Salamon and her collaborators met to discuss how to address the effects of HIV/AIDS on diverse communities in the region, the sociologists Peter Townsend and Peter Phillimore and the NHS information specialist Alastair Beattie published Health and Deprivation: Inequality and the North, a book-length study that drew on the influential Black Report (1980). Both studies demonstrated close links between ill health and material deprivation that were more sharply pronounced in the North East of England than anywhere else in the country. Both reports made clear that these regional disparities in health and mortality have “primarily structural causes, rooted in wider social inequalities” rather than in “individual lifestyle choices” and behaviours.39 Salamon’s approach to working with communities in the North East of England impacted by HIV and AIDS echoed Douglas Crimp’s contention in 1987 that “all productive practices concerning AIDS will remain at the grass-roots level. At stake is the cultural specificity and sensitivity of these practices”, particularly those relating to sexuality and drug use.40 For Salamon, this meant working with artists who were not necessarily from the North East of England, but who would be supported by Artists’ Agency and their project partners to embed themselves in the region during the project, which would allow them to have both a deep understanding of the cultural and economic specificities of the area and the experience and capacity to look beyond it to “a world living with HIV and AIDS”.

36Salamon worked for three years to acquire sufficient funding. She put together a patchwork of financial support from local, national, and international organisations including the Newcastle and Gateshead health authorities, Northern Arts, the National AIDS Trust, Newcastle City Council, the Baring Foundation, and the Commission of the European Communities, and in-kind support from local galleries and arts organisations such as Zone Gallery, the Laing Art Gallery (which provided office space), Projects UK, Cleveland Arts, and the Tyne International.41 The first financial contribution came from the Bishop of Durham (who had initiated the Bishops’ AIDS Ministry Group in the 1980s), a move that inspired other funders to take a risk on a project that engaged directly with sex, sexuality, addiction, and racism and in the early years of Section 28.42 Once funding was secured, Salamon worked with representatives of the service organisations and healthcare providers with whom she’d developed the concept to shortlist and interview artists, appointing Nicholas Lowe and Michael McMillan. While Lowe and McMillan worked concurrently across the year, they focused on distinct projects rather than collaborating directly.

41Brecht and Blind Date

Michael McMillan came to the HIV residency from a community arts and theatre background. Working primarily in London with Black theatre groups, he had developed techniques for leading improvisational creative writing workshops with sometimes vulnerable communities who did not necessarily have formal experience of art education or practice. McMillan’s methods were underpinned by a commitment to “always to work ethically, always to work with consent, always to … allow people to be anonymised, always to be gentle and tender, and empathetic”.43 While there were what McMillan called “Black British community-based HIV/AIDS initiatives” in the United Kingdom in the late 1980s and early 1990s, including the London-based Black HIV/AIDS Network (BHAN), he found that, in Newcastle,

43McMillan was struck by the work Salamon had done to galvanise local HIV/AIDS support organisations and healthcare providers but noticed that “issues of representation in terms of Black people [living with HIV] formed significant gaps in this network”.45 Nobody working in HIV/AIDS healthcare in the region could tell McMillan “about the level of HIV infection and incidence of AIDS amongst Black people in the North East. No figures existed”.46 McMillan told me that he found that “Black and Brown communities felt othered within Newcastle” and were “dealing with racism” as well as HIV.47 Connecting with these communities through discussions that addressed the homophobia and racism of mainstream media representations of people with HIV and Black people was particularly important, McMillan felt, when “they’re [imbibing] the kind of conventional mainstream narrative themselves. And so you’re trying to disrupt that”. This also involved addressing “tropes of homophobia within these communities … and their … perception of HIV”, as well as racialised stereotypes of Black British communities as inherently homophobic.48

45McMillan also found that “a white macho culture dominated the cultural political dynamics in the North East”, which “seemed to have emerged from a disenfranchised working class culture [which has] has lost its own self-esteem and identity in a post-Thatcherite Britain”.49 Visible markers of economic and cultural deprivation were rife in the region. McMillan was advised that the National Front were particularly active in Gateshead.50 A survey by Newcastle Civic Centre in 1990 found that 57 per cent of Black people in the city had experienced racist abuse and 45 per cent had had their homes or shops attacked.51 McMillan and Lowe arrived in Newcastle just a few months before young people living on the Meadow Well council estate in North Shields rioted after the death of two local teenagers, Dale Robson and Colin Atkins, following a police chase in a stolen car. The riots, in September 1991, spread westwards into the city, to Benwell, Elswick, and Scotswood. More than 300 people were arrested.52 As McMillan recalled, “mainly white youths went on the rampage” in these areas, which had higher proportions of Black and Asian residents than the rest of the city and the region.53 Rioters in Meadow Well forced out South Asian shopkeepers by setting their businesses on fire.54 Elswick was already infamous for anti-Black harassment and racist attacks.55 Writing about the North–South cultural divide in Art Monthly in October 1991, following the riots, Paul Usherwood, like McMillan, felt that machismo was also limiting creative regeneration efforts in the region: “there is talk of the new, squeaky-clean Tyneside of the future, but the dominant impression is of a macho, industrial region, a foreign country where they continue to do things differently”.56 The very real and racist violence that flared up in North Shields and Newcastle in 1991, Usherwood argued, “allowed the world”, Westminster, and the south of England in particular, “to see the North East as it always believed it to be: somewhere disturbingly, excitingly, incorrigibly other”.57

49At a conference at Durham University about HIV/AIDS in prisons held during the HIV residency, which he attended as part of his work with HM Prison Durham, McMillan found that he was “the only Black person present among two hundred delegates” and that “there was no discussion of race and racism in the prison system, and how HIV/AIDS impacted upon Black inmates who constitute over 40% of the prison population in Britain”.58 At HM Prison Durham, he spent several weeks working with Rule 43 inmates, vulnerable prisoners segregated from the general prison population for their own protection. Informal conversation was crucial to his approach to working with them. In general, McMillan had found that “any HIV-related education” in the North East was “framed by a sense of ethnic need, rather than Black people setting their own agendas”. Discussion-based workshops disrupted that patronising racialised dynamic by focusing on individual and shared experiences rather than stereotypes, displacing the alienating effects of universalising campaigns and community initiatives that centred white people, “making the personal political and the political personal”.59 At HM Prison Durham, McMillan recalled, “through improvisation and discussion, we explored themes such as sexual relationships among inmates” and “their perceptions of prison culture”. They also spoke openly about “relationships and rites of passage”, including death and “the differences between Black and white funerals and burials”.60

58In an essay about his experiences of the HIV residency for the book Living Proof, McMillan noted that, although his background is in community arts and theatre, “I use different media according to what I want to say—theatre, poetry, film, or visual arts. I try to combine qualities from all these art forms in order to transcend and break down the barriers between art forms”. For him, this was an explicit “reclamation of African art, where art and cultural forms are not separated, but functional (rather than decorative) in relating art to life”.61 It was informed, too, by Douglas Crimp’s writing on HIV/AIDS and cultural activism, particularly Crimp’s call for cultural producers and activists engaged in AIDS organising “to abandon the idealist conception of art. We don’t need a cultural renaissance; we need cultural practices actively participating in the struggle against AIDS”.62 Indeed, McMillan saw his role in the HIV residency as “being not simply that of an artist but as a cultural activist”.63 As part of his contribution to North East AIDS Week in May 1992, for example, he commissioned a Black HIV/AIDS Training Weekend, led by BHAN “for Black people in the voluntary and statutory sectors in the North East”.64

61McMillan was inspired by the cultural activism of the New York-based art collective Gran Fury, which “began as an ad hoc committee” of members of ACT UP New York, by reading articles about HIV/AIDS by Crimp and Larry Kramer, and by an Arts-Council-funded visit to the east coast of the United States during the HIV residency, which enabled him to meet Black-led organisations engaged in the struggle against HIV/AIDS, including Bebashi (Blacks Educating Blacks about Sexual Health Issues) and Pomo Afro Homos.65 He identified discussion-based workshops and collaborative public performances as practices that would combine “current developments in the aesthetics of Black theatre with the political activism [he] had seen in the States and experienced in Newcastle” through organisations such as the AIDS Community Trust (ACT) and the North East branch of OutRage!, the British lesbian and gay rights group formed in London in 1990.66 He worked hard to gather “a network of ‘strong, bad, and active’ Black people”, with support from the Black Arts Network and “a host of Black artists and cultural workers”, alongside “a number of progressively minded students [who] were already exploring HIV/AIDS issues in their work”.67 Women played an important role in McMillan’s workshops and performances, as they did in the work of BHAN and Bebashi.68

65The Last Blind Date Show, a key component of North East AIDS Week, which marked the end of the HIV residency, brought together the conversational workshop methods that McMillan had drawn on and further developed as part of his work with Artists’ Agency and his long-standing interest in Brechtian techniques and contemporary North American Black theatre (fig. 5). The decision to stage a spectacular public performance in the centre of Newcastle was also influenced by the distinctive live art culture that was embedded in the city in this period, exemplified by international festivals such as the Tyne International and the work of Projects UK and its predecessor, the Basement Group, which commissioned site-specific performances and participatory arts projects from an international roster of artists, supported by public funding through Northern Arts. “We were already aware that there was a kind of avant-garde tradition” in the city, McMillan told me, and this “gave me permission to do The Last Blind Date Show in the way I did it”.69 The Basement Group and Project UK’s approach to commissioning and staging public performances was closely aligned with McMillan’s. Andrew Wilson described the live art scene in Newcastle in the 1980s and 1990s as consisting of work “that did not so much document lived experience as become lived experience, in the process breaking down the barriers between audience and artist”.70 McMillan extended this by working with non-trained actors to perform a work they had co-created in workshops as part of the HIV residency.

69

McMillan envisaged The Last Blind Date Show as a send-up of “a whole set of exclusive patriarchal, heteronormative, restrictive, oppressive kind of tropes” on mainstream British television, as well as public health messaging and racist and homophobic stereotypes about HIV/AIDS. The performance was intentionally loud and comedic. Working with non-trained actors in public, McMillan told me, “everything, because you’re working on the street, everything has to be over the top. It is melodramatic. You have to make it exaggerated. You’re creating spectacle and sensation. And that’s what we did”.71 McMillan developed the performance “from a kind of Brechtian approach: we’re telling you, yes, this is a performance”.72 With the aim of exploding stereotypes and preconceptions, the contestants’ questions referred directly to the experience of dating while living with HIV/AIDS. When Shabazz asks, “if I were HIV positive would you want to go out with me?”, Anon replies: “I’ll answer your question with a question of my own. If I said that I had a packet of condoms in my pocket would you wanna go out with me?”73 Shabazz is openly disgusted when another contestant, Xeno, repeats “all the racist hype about AIDS” coming from Africa.74

71McMillan and the performers drew attention to racism in both mainstream HIV/AIDS health education materials and primetime British television in a very public place, conscious of the threat of racist violence that ran through the city in the early 1990s:

75My invigilators, kind of soft security, were a group of people, students, mixed, who wore dark glasses and T-shirts that said “No, white woman, I don’t want your handbag”. So you know we’re being provocative, but I was aware we needed invigilation. We needed some kind of protection because anything could happen.75

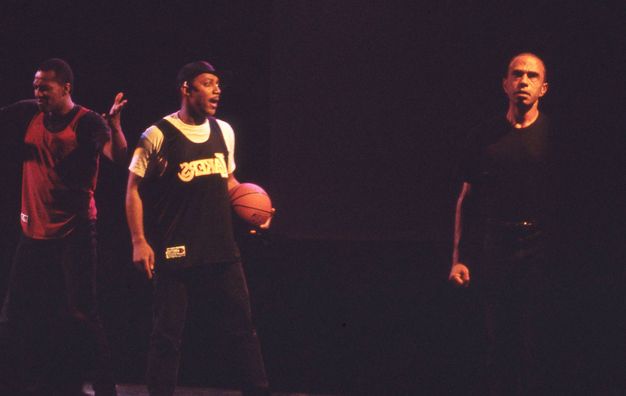

“Most of the actors in the piece”, he recalled, “well, half of them were Black. That’s not something you’d see on Blind Date”.76 Anon, played by a Black actor, emphasised this during the performance: “I hope you’ve got somebody Black for a change … I mean you never have two Black people on at the same time do you?”77 Presenting multiple perspectives and Black British experiences of HIV/AIDS was central to the concept of The Last Blind Date Show. In this McMillan drew from the performance work of Pomo Afro Homos, particularly Fierce Love (1991) and Dark Fruit (1992). Dark Fruit was staged at Live Theatre in Newcastle during North East AIDS Week, following an invitation from McMillan, who’d seen the performance on his visit to Washington, DC, and New York City earlier in the HIV residency (fig. 6). Both works were made up of vignettes that presented different aspects of Black gay male experience in the United States, particularly at its intersections with class and gender, from the difficulties of growing up queer in a conservative Black family to erotic fantasies of two Black men having sex in the back room of a predominately white club, to a defiant story of three effeminate Black gay men resisting gendered prejudice in Black gay community spaces. Other vignettes parodied contemporary North American theatre’s representation of Black gay men and offered “an angry challenge to the systemic forces that sustain AIDS in the Black gay community”.78 David Román wrote that, while this approach was partly about showing the group’s versatility as performers, through its combination of specificity and multiplicity Pomo Afro Homos also “contest[ed] any essentialised reading of their bodies since they cannot be reduced to one notion of ‘African American homosexual’; the postmodern, or pomo, is located in this free play of identity and performance”, and that, while they “insist on being heard as Black gay men, they offer no fixed reading of a Black gay male identity. Spectators, regardless of race or sexual orientation, are asked to consider what it means to be Black and gay”.79

76

Given the highly visual and public nature of The Last Blind Date Show, it is perhaps surprising that no photographs of it appear in the book Living Proof, which includes the full script. This is interesting not least because this very public performance was one of McMillan’s contributions to the residency that could be shared, unlike the conversations in the prison workshops. For Román, writing in 1998, “AIDS performance raises questions concerning the practices of official documentation, of theatre history”.80 Writing about AIDS and performance, he argued, “can only be a partial recovery of a history with no point of origin and no predetermined place of destination” because “most AIDS performances do not aspire to canonicity. Instead AIDS performances challenge our understanding of AIDS so that we better learn to cope with its effects”:81 “AIDS theatre and performance calls for a new mode of criticism appropriate to the demands of the historical conditions of the crisis and the innovative artistic and political improvisations” it has necessitated.82 In The Last Blind Date Show, the liveness and contingent nature of the performance, its improvised and potentially volatile relationship with the local audience, and the specificity of the site (central Newcastle on a busy Friday afternoon) were vital to its effectiveness and its meaning, “living proof” of the complex realities of life with HIV/AIDS in the North East of England.

80The Necessity of Metaphor

Nicholas Lowe had experience of making work about HIV/AIDS before he took up the HIV residency in Newcastle. In an essay for the book Living Proof, he wrote that his motivation to work with people affected by HIV/AIDS came “from a combination of personal distress and anger” and that his approach, like McMillan’s, was informed in part by the work of Larry Kramer and ACT UP New York.83 “In the particular social situation of the late 1980s”, Lowe recalled, “it became a matter of life-threatening importance to engage in safer sex both in theory and in practice”.84 He aimed to record the lived experiences of people with HIV and AIDS, to “understand how it now makes up part of our society”, and, paraphrasing Kramer and Gran Fury, “to give those who see themselves as affected by HIV the means to ensure that the ‘record’ does ‘show’”—a reference to Let the Record Show …, an installation in the windows of the New Museum of Contemporary Art at 583 Broadway in Manhattan from November 1987 to January 1988, produced by members of ACT UP New York.85

83Lowe’s installation (Safe) Sex Explained, which he had developed in 1988 as a student at the Slade School of Fine Art, was included in the exhibition Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology (1990–91), curated by Tessa Boffin and Sunil Gupta. The work consisted of four sheets of vinyl, each measuring eight feet by four feet, two of which were opaque and two transparent, with poetic text about desire, pleasure, loss, and fear of infection printed onto them. The sheets were intended to be hung as pairs facing each other, a transparent sheet in front of an opaque one, in a space only just larger than the components of the installation. The space between the paired vinyl sheets was filled with “crumpled, photocopied pages from a gay pornographic magazine depicting pre-safe sex activities”.86 The sheets were lit only by projectors, which showed close-up images of skin and hair and of used condoms in a north London cruising spot, “the first”, Lowe wrote later, “allied to a discussion of representation and subjectivity and the second to the idea of evidence and proof of changing sexual habits”.87 In the Ecstatic Antibodies book, photographic documentation of the installation was included alongside a conversation between Lowe and Pam Toussaint, a local authority officer with responsibility for training social workers.

86(Safe) Sex Explained was shown at Impressions Gallery in York from January to March 1990 as part of Ecstatic Antibodies. The exhibition was meant to travel to Viewpoint Gallery in Salford in June but was cancelled pre-emptively following pressure from Salford City Council, ostensibly because works in it contained “pornographic material” and were thus “not suitable for children”.88 This statement referred, at least in part, to elements of (Safe) Sex Explained. Lowe and the writer and artist Emmanuel Cooper both saw fear of prosecution under Section 28 of the Local Government Act as the root cause of the withdrawal of the exhibition. But, Lowe noted, “rather than invoking the Clause by name the [local] authority internalised its reasoning in the cause of accessibility”.89 In light of this, Ikon Gallery in Birmingham stepped in to host Ecstatic Antibodies. However, while Lowe was helping to install his work there, he found that some of the photocopies for the installation had gone missing on arriving at the gallery, and he was pressurised to replace them with blank pieces of paper, alongside an unauthorised statement declaring that “in the interests of ‘audience access’ some of the works in the exhibition had been altered”.90 At this point he also discovered that the police had been called to Impressions (which did not receive local authority funding) earlier in the year, after members of the public and a local member of parliament had complained that work in the exhibition was pornographic.91

88This was the oppressive and suspicious context in which Lowe first made and exhibited work about HIV and AIDS, and it prompted him to stop producing HIV/AIDS-related work temporarily. He undertook a prestigious artist residency in Bethune in northern France, where he continued to work with photography but in a more metaphorical and symbolic way. He engaged closely with local residents and specific historic sites in the town. In the installations and photography he produced in Bethune, industrial and domestic objects “were utilized to stand in for the body, everyday substances like stones, seeds, soil and living plants were symbolically charged in the context of a discussion of sex, disease and death”.92 He contended that his earlier work had “effectively been forced to take on a status like that of pornography itself, as ‘dirty’ or ‘private’ pictures” that he could make but not exhibit.93 His new work engaged more critically with the politics of AIDS representation through coded images and symbolism. This was a means of challenging phobic depictions of people with AIDS in mainstream media as wasted, infectious, and deadly: “I was clear that my work should resist representations of this kind, in favour of allegorical approaches and discussions that employed metaphor”.94

92Lowe was not necessarily arguing that AIDS should be understood as a metaphor but that metaphorical representation and engaging with AIDS through metaphor could allow artists to make nuanced work about AIDS that might evade censorship while at the same time challenging negative media depictions and stereotypes of people living with HIV and AIDS. Metaphor could allow for a nuanced conversation about HIV/AIDS and its effects rather than a purely didactic one. By the time he was interviewed by Artists’ Agency for the HIV residency, Lowe told me:

Lowe’s shift in approach corresponded with progressive thinking about AIDS representation and public engagement in the United Kingdom and North America. In his contribution to the book Ecstatic Antibodies, Simon Watney argued that “it is entirely wrong to imagine that disease can, or should, be stripped of metaphor” and called for readers “to appreciate the constant resonance of metaphor without which language would be no more than a code, invariant, inhuman—because it would no longer be social”.96 In 1989 Jan Zita Grover argued for “the necessity of metaphor” in thinking about AIDS, against Susan Sontag. Critiquing Sontag’s 1987 essay AIDS and Its Metaphors, she wrote that “constructing less devastating ways of ‘regarding illness’ … is not simply a matter of promoting ideas of sickness ‘resistant to metaphorical thinking’” but of “assessing what’s available metaphorically, what the implications of current metaphors may be for various audiences, and who benefits from those conceits most commonly at work in media, medicine, politics, and public health”.97 She proposed that “metaphors normalize the unfamiliar, domesticate it” and could also facilitate supportive and personal conversations about the lived experience of HIV and AIDS.98

96Dialogic workshops and a conceptual approach to photography, informed by the work of Jo Spence and Rosy Martin, were central to Lowe’s approach to using metaphor in working with people living with HIV and AIDS as part of the HIV residency. Like McMillan, Lowe led workshops at HM Prison Durham. By the time he arrived in Newcastle, he felt strongly that “one constituency that was not being addressed, and … kept coming up in the news … were prisoners with HIV”.99 Lowe was supported to work with HIV-positive prisoners at HM Prison Durham by the Bishop of Durham and the prison’s chaplain, through the Bishops’ AIDS Ministry, and alongside HIV counsellors. The sessions were conversational and involved talking with men and women in the prison about their experiences of incarceration and their relationship to HIV/AIDS. This led to the development of a body of photographic work by Lowe, supported by Artists’ Agency as part of his artist residency. At Bethune, Lowe had produced a series of photographs that explored the city’s medieval walls as “a metaphor for ignorance in the light of HIV”, where the “walls in people’s minds were as strong as that in the town”.100 At Durham, Lowe approached the prison’s walls similarly, thinking about “confinement as a metaphor for HIV—the idea of existing in the world, while not being part of society” (fig. 7).101 It was, he told me “a really productive way of me thinking about these questions of identity and incarceration as a metaphor … and as an actual thing”.102 Angela, an addiction counsellor and volunteer with the ACT, whom Lowe interviewed for the book Living Proof, spoke similarly of people “in a prison and in the prison of HIV”.103 Lowe also recalled that “at that time it felt like gay men were criminals, were being criminalised, were being discriminated against, and we had chosen to bring the virus upon ourselves was the rhetoric. So [using metaphor] was about … finding ways to articulate and nuance that conversation”.104 Working with metaphors like that of the wall also allowed people in prison to speak about their experiences without discussing specific criminal offences. And, for Lowe, “this metaphor of containment is also one of surveillance”: from his own experiences of censorship in Salford and Birmingham, the walls “talk of silencing and censorship” in relation to conversations and cultural production about HIV/AIDS.

99

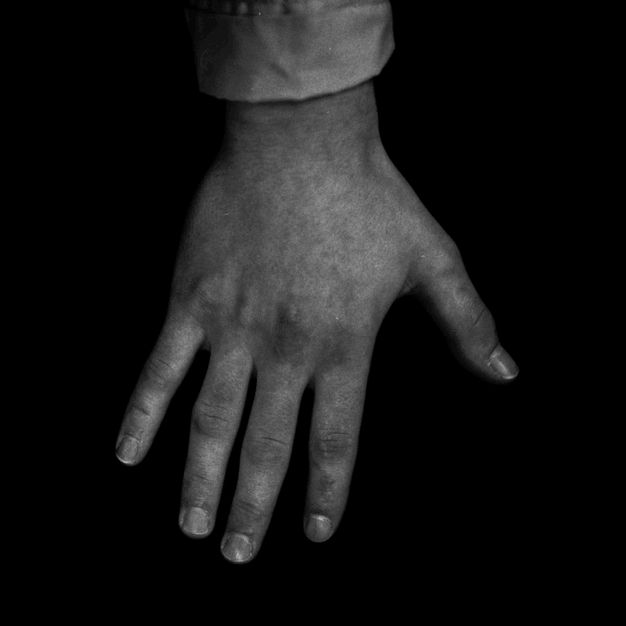

However, the photographs Lowe produced as part of the HIV residency, informed by his visits to HM Prison Durham, were not only of prison walls. While the metaphor of the wall, and more broadly that of the prison and imprisonment, informed his approach to working with people in prison deeply, he focused on photographing the hands of people he met there, “those whose lives are under scrutiny and the subject of Her Majesty’s Pleasure” (fig. 8).105 This allowed him to tenderly underscore his participants’ physical presence, proof of their incarceration and their humanity, while ensuring that they remained anonymous. As he took the photographs, he “talked to each of them about the virus and ways of protecting against infection”.106 Some of them disclosed their HIV status to Lowe, though this was not a prerequisite of participation. The primary aim was “to talk to people”.107 Writing about his experiences at HM Prison Durham, Lowe emphasised the role of conversation in this series:

105108My work here has perhaps been most effective in the dialogues I have had with the individuals. If my photography seems incidental to that, it is because the photographs are not “pictures”. They do not present vistas, but details.108

Like Lowe’s use of metaphor, this specificity was key, allowing participants to address the reality of their incarceration and their relationship to HIV without having to provide visual proof of its impact through straightforward documentary photography or portraiture. Lowe’s approach refused both the pathologising images of gay men "bearing the visual evidence of the ravages of a “killer disease’” and the near invisibility of representations of women with HIV/AIDS in mainstream British media in the 1980s and early 1990s.109

109Hands appeared in photographs produced by participants in workshops outside the prison too. Three sets of hands appear in a photograph by Lynne Otter “about the delicate negotiations that take place during a sexual encounter, in the light of HIV and safer sex practices”, each pair interlocking above the words “Loving memory”. In a set of photographs by Neil Mitchell, sheets of paper printed with text highlighting questions about media representations of people with AIDS and state surveillance are passed between two hands and held up in front of projected images of dictionary definitions of impactful words for people living with HIV: “immigrant”, “media”, “mortgage”, and “support”.110 One text reads “Mortgages: why do I have disclose whether I’ve had an HIV antibody test?”, and another “Media: why have you stigmatised me and blamed for this condition?” At these workshops participants were asked to consider their feelings in relation to HIV/AIDS and its social implications. “How can we begin to visually represent our feelings?”, Lowe asked them.111 Participants were invited to bring “a collection of material—objects, newspaper cuttings, personal artefacts, collections[—]which they feel is important to their life since AIDS”.112 They brought flowers, leather gear, lube, candles, and wooden artists’ mannequins. They took photographs of their homes and public parks. The work they produced, some of which was exhibited at Zone Gallery and Laing Art Gallery as part of North East AIDS Week, engaged with the theme of visibility in relation to HIV/AIDS through metaphor, allowing them to feel seen without being exposed.

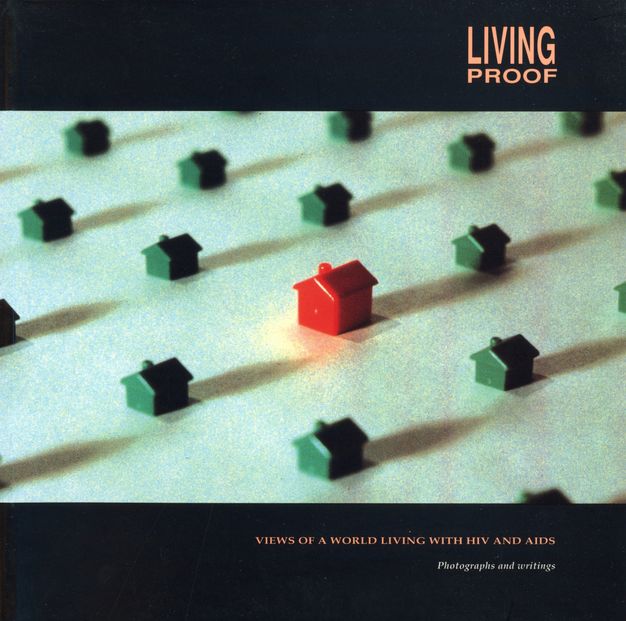

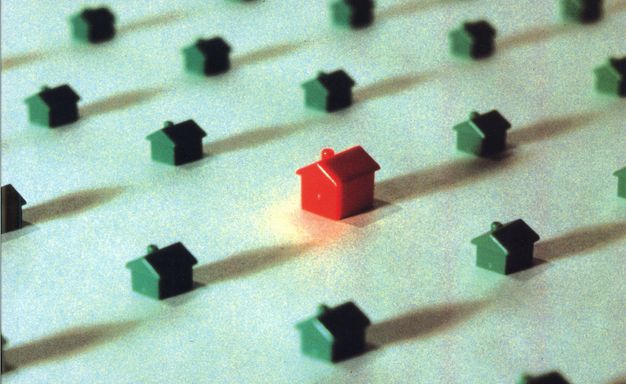

110One of the most striking works developed as part of the HIV residency was produced in this set of workshops by a participant called Keith Livingstone (fig. 9). At the time, Livingstone was living with AIDS, had worked extensively in community support for people impacted by HIV/AIDS in Tyneside, and had been “a member of the management support group for the residency since day one”.113 Livingstone’s photograph shows a collection of green Monopoly houses with a single red hotel token at the centre, arranged on what appears to be a Formica tabletop, giving the homogeneous effect of an endless manicured suburban lawn. Livingstone wrote in his accompanying statement that the work “represents an individual’s experience of HIV. Individuals living with a positive diagnosis may become very self-conscious, and feel as though their HIV status is written all over their face, for all to see”.114 The red hotel, slightly larger and more sharply in focus than the green houses that surround it, hints at blood and inflammation and, more simply, embodies a sense of difference and isolation. It does so without recourse to bodily imagery or stereotypes, refuting what Jan Zita Grover calls “the dominant contamination–contagion metaphor”.115 The directness of Livingstone’s approach to metaphor developed dialogically in the workshops, through conversation with Lowe and other participants. In its simplicity and straightforwardness this work in many ways exemplifies Lowe’s aim of “bringing an audience to a place of understanding rather than teaching them something”.116 It was part of the national Billboard Art Project supported by the outdoor advertising firm Mills and Allen, the BBC, and the Radio Times in May 1992 in cities including Glasgow, Birmingham, Derry, and Newcastle (fig. 10), and included in the exhibition Fatal Attractions: AIDS and Syphilis from Medical, Public and Personal Perspectives at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine in May 1995.

113

In his writing about AIDS and performance in North America from the late 1980s and early 1990s, David Román quoted the feminist scholar Kate Davy as he explored how performance can produce what she called “spectatorial communities” among those who often find themselves surveilled or ignored: “For spectators whose sole experience with dominant culture is one of either being erased entirely or foregrounded as tragically ‘Other’ against a (hetero)sexuality inscribed as fiercely normative, the experience of being addressed as if inhabiting a discursive space, an elsewhere eked out in the gaps of hegemonic representations, is both profound and exhilarating”.117 The same might be said of the vital validating experience of being invited to explore one’s lived experience of HIV/AIDS slowly through metaphor and conversation. Lowe argued that this was “an approach that avoided impersonal representations or the depersonalization of AIDS as a complex”, exploring “social issues and personal experiences” while refusing individual exposure and “resisting the AIDS mythology” that underpinned much mainstream media and public health messaging.118

117Living Proof

What does it mean to construct and share “views of a world living with HIV and AIDS” from the vantage point of Newcastle upon Tyne? What is at stake in tracing this history now? As Jih-Fe Cheng, Alexandra Juhasz, and Nishant Shahani argue, “it matters where we locate the [HIV/AIDS] crises, how we temporalize their multiple durations, and when and how we identify, name, and categorize their impacts”.119 I first encountered photographs of The Last Blind Date Show in Helix Arts’ temporary offices on Bedford Street in North Shields, eight miles along the River Tyne from Newcastle. While Helix Arts cares for a range of material relating to the Living Proof project, including photographic documentation of performances and artworks produced by participants, this archive is informal and relatively precarious, not preserved in any formal sense by an institutional archive or library. North Shields is currently undergoing redevelopment as part of North Tyneside Council’s North Shields Cultural Quarter project. Like much of the North East of England, the area has struggled as a consequence of the loss of heavy industry since the 1960s; subsequent long-term unemployment, disinvestment, and local authority funding cuts; and over a decade of austerity policies at the national level. The North of England, particularly the North East, has lower life expectancy and higher health inequalities than the rest of England, as it did when HIV/AIDS emerged in the 1980s and while McMillan, Lowe, and Salamon were working on Living Proof in the early 1990s.120 Since 2010, austerity policies and central government efforts to “reduce geographical disparity within the United Kingdom” through the economic policy known as “levelling up”, introduced in the Conservative Party manifesto immediately prior to the 2019 general election, have failed to address these regional differences, leaving the North East of England at a critical impasse, exacerbated by the cost-of-living crisis.121 Helix Arts continues to respond to this regional context in its community arts work today.

119Living Proof is an overlooked but vital part of British HIV/AIDS histories and histories of HIV/AIDS-related cultural production in the United Kingdom. It did not, to borrow from David Román, “aspire to canonicity” nor wish for obscurity.122 One of the most striking things about the project from the perspective of the present is that it looked outwards to “a world living with HIV and AIDS” while engaging deeply with the breadth of constituencies in the United Kingdom impacted by HIV and AIDS in the early 1990s. It included gay men living with HIV and AIDS but also went beyond this community, working closely with Black and South Asian heterosexual people living with HIV and AIDS, women, people with haemophilia, people with drug and alcohol dependency, and people in prison. It made connections with HIV/AIDS organising and cultural production in North America, which McMillan, Lowe, and Salamon viewed through the prism of solidarity and partnership rather than that of centre and periphery. The story of Living Proof also speaks to the distinctive funding, gallery, and festival networks active in the region in the late 1980s and early 1990s, many of which are now defunct. Living Proof’s North East location, specifically the cultural ecosystem supporting community art and live art in the 1980s and early 1990s, made the project possible.

122Living Proof centred racialised experiences of HIV/AIDS, and included women, people in prison, and people with haemophilia, in workshops and performances and in the development of the residency from the very beginning, identifying them as vital (rather than as marginal or additional) both to the project and to understanding the global HIV/AIDS crisis more broadly. In this way, the story of Living Proof expands understanding of the scope and scale of HIV/AIDS-related cultural production in the United Kingdom and emphasises the value of a decentred and regional approach to UK HIV/AIDS histories. As Gareth Longstaff notes in an essay exploring the representation of Newcastle’s queer bar scene in Channel 4’s first gay and lesbian magazine-style TV programmes Out on Tuesday (1989) and Out (1990–94):

123In the late 1980s and early 1990s a decline in employment in shipbuilding, coalmining and factory labour, and the subsequent move to tertiary-based modes of production in the North East meant that how sexuality and sociality were being articulated there was always qualitatively different to how they were understood and mapped in London and elsewhere.123

To historicise Living Proof now means to engage with the cultural and political specificity and distinctiveness of the region, its characteristic sociability, its long history of health inequalities and social deprivation, and its rich live art and community arts infrastructure. Doing so offers strategies through which historians of HIV/AIDS cultural production in the 1980s and after might avoid intimating that UK HIV/AIDS histories and archives more generally simply need to look outside London or beyond canonised or otherwise well-documented figures such as Derek Jarman, an approach that often reiterates the centre–periphery binary that has rendered these regional archives and histories precarious and hard to see in the first place. It involves starting from Newcastle, understanding it on its own terms, and recognising the economic and political challenges that have led to this situation of archival precarity and historical invisibility, informed by Eric A. Stanley’s call to action—that, to develop truly global and inclusive HIV/AIDS histories, we must work collectively, regionally, and in a non-extractive way “so that connections of depth might be made through locations and not simply over them”.124

124Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to Esther Salamon (1951–2023), Michael McMillan, and Nicholas Lowe for talking with me about their experiences of Living Proof and the North East of England. Dan Goodman provided invaluable research assistance and good conversation about Geordie cultural production. Cheryl Gavin, director of Helix Arts, was a brilliant interlocutor in this work. Thanks also to James Boaden, Ed Webb-Ingall, Flora Dunster, Laura Guy, Theo Gordon, Al Hoyos-Twomey, Theodore (Ted) Kerr, and Gavin Butt for ongoing conversations about HIV/AIDS, art, and the regional.

About the author

-

Fiona Anderson is an art historian based in the Fine Art department at Newcastle University. Her work explores queer art histories from the 1970s to the present, particularly in the context of the ongoing HIV/AIDS epidemic and in relation to preservation and archiving practices. She is the author of the book Cruising the Dead River: David Wojnarowicz and New York’s Ruined Waterfront (University of Chicago Press, 2019), which examines the erotic and political roles that New York’s post-industrial landscape played for various queer communities in the city, and co-editor, with Glyn Davis and Nat Raha, of “Imagining Queer Europe Then and Now”, a special issue of Third Text (January 2021). Fiona’s writing has also been published in journals such as Performance Research, Journal of American Studies, and Oxford Art Journal. She is also a DJ. Her radio show and club night Wildflowers offers a queer feminist and global perspective on country music, folk, and Americana.

Footnotes

-

1

Michael McMillan, “The Last Blind Date Show”, in Living Proof: Views of a World Living with HIV and AIDS; Photography and Writings, ed. Nicholas Lowe and Michael McMillan (Sunderland: Artists’ Agency, 1992), 138. ↩︎

-

2

Michael McMillan, interview by the author, 1 November 2023. ↩︎

-

3

Ibid. ↩︎

-

4

Nicholas Lowe and Michael McMillan, eds., Living Proof: Views of a World Living with HIV and AIDS; Photography and Writings (Sunderland: Artists’ Agency, 1992). ↩︎

-

5

Bill Lancaster, “Newcastle – Capital of What?'”, in Geordies: Roots of Regionalism, 2nd ed., ed. Robert Colls and Bill Lancaster (Newcastle upon Tyne: Northumbria University Press, 2005), 55; Robert Colls and Bill Lancaster, “Preface”, ibid., xiv. ↩︎

-

6

This is the subtitle of the book Lowe and McMillan co-edited, Living Proof: Views of a World Living with HIV and AIDS; Photography and Writings. ↩︎

-

7

See Richard Bolton, ed., Culture Wars: Documents from the Recent Controversy in the Arts (New York: New Press, 1992). ↩︎

-

8

Esther Salamon, “Foreword”, in Living Proof, ed. Lowe and McMillan, 9. ↩︎

-

9

Ibid. ↩︎

-

10

Jih-Feh Cheng, Alexandra Juhasz, and Nishant Shahani, “Introduction”, in AIDS and the Distribution of Crises, ed. Jih-Feh Cheng, Alexandra Juhasz, and Nishant Shahani (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020), 21. ↩︎

-

11

Viviane Namaste, “AIDS Histories Otherwise: The Case of Haitians in Montreal”, in AIDS and the Distribution of Crises, ed. Cheng, Juhasz, and Shahani, 131. ↩︎

-

12

Ibid., 141. ↩︎

-

13

George Severs, Radical Acts: HIV/AIDS Activism in Late Twentieth-Century England (London: Bloomsbury, 2024). ↩︎

-

14

Marika Cifor, Viral Cultures: Activist Archiving in the Age of AIDS (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2022), 4. See also Robb Hernández, Archiving an Epidemic: Art, AIDS, and the Queer Chicanx Avant-Garde (New York: NYU Press, 2019), and Alexandra Juhasz and Theodore Kerr, We Are Having This Conversation Now: The Times of AIDS Cultural Production (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022). ↩︎

-

15

“Our History”, Helix Arts, accessed 8 April 2024, https://www.helixarts.com/about-us/our-history. ↩︎

-

16

Gabriel N. Gee, Art in the North of England, 1979–2008 (London: Routledge, 2017), 59. ↩︎

-

17

Paul Usherwood, “North and South”, Art Monthly 150 (October 1991): 2. ↩︎

-

18

Gee, Art in the North of England, 78. ↩︎

-

19

Usherwood, “North and South”, 2. ↩︎

-

20

Natasha Vall, Cultural Region: North East England 1945–2000 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011), 136. ↩︎

-

21

Ibid., 134; see also 135–37. ↩︎

-

22

Malcolm Miles, Art, Space and the City: Public Art and Urban Futures (London: Routledge, 1997), 75. ↩︎

-

23

Ibid. ↩︎

-

24

Ibid., 76. ↩︎

-

25

Ibid., 77. ↩︎

-

26

Salamon, “Foreword”, 9. ↩︎

-

27

Simon Watney, “Taking Liberties: An Introduction”, in Taking Liberties: AIDS and Cultural Politics, ed. Erica Carter and Simon Watney (London: Serpent’s Tail, 1989), 19. ↩︎

-

28

Ibid. ↩︎

-

29

Salamon, “Foreword”, 9. ↩︎

-

30

Ibid. ↩︎

-

31

Ibid. ↩︎

-

32

Tessa Boffin and Sunil Gupta, “Introduction”, in Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology, ed. Tessa Boffin and Sunil Gupta (London: Rivers Oram Press, 1990), 1, 4. ↩︎

-

33

Robert Colls, “Born-Again Geordies”, in Geordies, ed. Colls and Lancaster, 2. ↩︎

-

34

Salamon, “Foreword”, 9. ↩︎

-

35

Esther Salamon, interview by the author, 15 February 2023. ↩︎

-

36

Petra Küppers, Community Performance: An Introduction (London: Routledge, 2019), 3. ↩︎

-

37

Peter Phillimore, Alastair Beattie, and Peter Townsend. “Widening Inequality of Health in Northern England, 1981–91”, BMJ 308, no. 6937 (1994): 1127. ↩︎

-

38

Nicholas Lowe, “The Interviews: Health Advisors from the Region”, in Living Proof, ed. Lowe and McMillan, 19. ↩︎

-

39

Peter Townsend, Peter Phillimore, and Alastair Beattie, “New Preface to the 2022 Reissue of Health and Deprivation”, in Health and Deprivation: Inequality and the North, rev. ed., ed. Peter Townsend, Peter Phillimore, and Alastair Beattie (London: Routledge, 2023). In the book’s revised publication in 2023, the authors note that “the UK continues to exhibit an unnecessarily bleak picture of persisting and even widening inequalities in health”. ↩︎

-

40

Douglas Crimp, “How to Have Promiscuity in an Epidemic”, October 43 (1987): 265. ↩︎

-

41

Living Proof, ed. Lowe and McMillan, n.p. ↩︎

-

42

Salamon, interview. The Bishop of Durham’s financial support for the project is also noted in the list of funders provided in Living Proof, ed. Lowe and McMillan, n.p. ↩︎

-

43

McMillan, interview. ↩︎

-

44

Michael McMillan, “Brother to Brother: A Rereading of Black Masculinities in Embodied Performance”, in The Male Body in Representation: Returning to Matter, ed. Carmen Dexl and Silvia Gerlsbeck (Cham: Springer, 2022), 36. ↩︎

-

45

Michael McMillan and Nicholas Lowe, “Living Proof in Words and Pictures”, Mail Out: Arts Work with People, October–November 2022, 21. ↩︎

-

46

Ibid. ↩︎

-

47

McMillan, interview. ↩︎

-

48

Ibid. ↩︎

-

49

McMillan and Lowe, “Living Proof in Words and Pictures”, 21. ↩︎

-

50

McMillan, interview. See also Adrian Lobb, "TV Historian David Olusoga: “My Family Were Driven from Our Home by the National Front’”, Big Issue, 2 October 2023, https://www.bigissue.com/culture/tv/union-with-david-olusoga-documentary-upbringing-racism. ↩︎

-

51

Beatrix Campbell, Goliath: Britain’s Most Dangerous Places (London: Methuen, 1993), 76. Campbell notes here that in a similar survey undertaken in Sheffield 25 per cent of Black people reported having experienced racist abuse and in Waltham Forest in north-east London the figure was 14 per cent. ↩︎

-

52

Ibid., ix. ↩︎

-

53

McMillan and Lowe, “Living Proof in Words and Pictures”, 21. Campbell notes that in the West End of Newcastle Black and Asian people made up 12 per cent of the population, compared to 3 per cent elsewhere in the city. ↩︎

-

54

Paul Wilkinson, “12 Accused after Riot on Estate”, The Times, 14 July 1992, 3. Wilkinson notes that the rioters shouted, “Let’s burn out the P—!” while doing so. For a detailed analysis of the causes and effects of the riots at North Shields, Elswick, Scotswood, and Benwell, see Campbell, Goliath. ↩︎

-

55

See ibid., 75–90. ↩︎

-

56

Usherwood, “North and South”, 2. ↩︎

-

57

Ibid. ↩︎

-

58

McMillan and Lowe, “Living Proof in Words and Pictures”, 21. ↩︎

-

59

Ibid. ↩︎

-

60

Michael McMillan, “Introduction to the Writer’s Residency and Commission”, in Living Proof, ed. Lowe and McMillan, 106. ↩︎

-

61

Ibid., 105. ↩︎

-

62

Crimp, “Cultural Analysis / Cultural Activism”, October 43 (1987): 7, quoted by McMillan in McMillan and Lowe, “Living Proof in Words and Pictures”, 21. ↩︎

-

63

McMillan, “Introduction to the Writer’s Residency and Commission”, 105. ↩︎

-

64

This information is from the North East AIDS Week flyer, which Nicholas Lowe shared with me. ↩︎

-

65

Gran Fury, “Gran Fury talks to Douglas Crimp—Interview”, Artforum, April 2003, https://c4aa.org/2008/06/gran-fury-talks-to-douglas-crimp. ↩︎

-

66

McMillan, “Introduction to the Writer’s Residency and Commission”, 105. ↩︎

-

67

Ibid., 101–2. ↩︎

-

68

“Training Courses May–August 1991 / Black HIV/AIDS Network”, Wellcome Collection, 1991, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/nackmpdy. ↩︎

-

69

McMillan, interview. ↩︎

-

70

Andrew Wilson, “Notes Towards the Inevitability of History”, in This Will Not Happen Without You: From the Collective Archive of the Basement Group, Projects UK and Locus+ (1977–2007) (Sunderland: University of Sunderland Press, 2007), 18. ↩︎

-

71

McMillan, interview. ↩︎

-

72

Ibid. ↩︎

-

73

McMillan, “The Last Blind Date Show”, 143. ↩︎

-

74

Ibid., 149. ↩︎

-

75

McMillan, interview. ↩︎

-

76

Ibid. ↩︎

-

77

McMillan, “The Last Blind Date Show”, 139. ↩︎

-

78

David Román, Acts of Intervention: Performance, Gay Culture, and AIDS (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), 174. ↩︎

-

79

Ibid., 164. ↩︎

-

80

Ibid., xiv. ↩︎

-

81

Ibid., xv, xxiv. ↩︎

-

82

Ibid., xxiv. ↩︎

-

83

Nicholas Lowe, “Introduction to the Photographic Residency and Commission”, in Living Proof, ed. Lowe and McMillan, 11. ↩︎

-

84

Nicholas Lowe, “Who Needs a Prosecution to Make a Point? The Forgotten British Culture Wars”, Social Identities 13, no. 2 (2007): 148. ↩︎

-

85

Lowe, “Introduction to the Photographic Residency and Commission”, 11. ↩︎

-

86

Nicholas Lowe, “(Safe) Sex Explained”, in Ecstatic Antibodies, ed. Boffin and Gupta, 75. ↩︎

-

87

Lowe, “Who Needs a Prosecution to Make a Point?”, 151. ↩︎

-

88

From a statement provided to the BBC by Salford City Department of Arts and Leisure, quoted in Lowe, “Who Needs a Prosecution to Make a Point?”, 152. ↩︎

-

89

Ibid., 153. ↩︎

-

90

Ibid., 155. ↩︎

-

91

Ibid., 153–54. ↩︎

-

92

Ibid., 156. ↩︎

-

93

Ibid., 157. ↩︎

-

94

Ibid., 150. ↩︎

-

95

Nicholas Lowe, interview by the author, 15 December 2023. ↩︎

-

96

Simon Watney, “Representing AIDS”, in Ecstatic Antibodies, ed. Boffin and Gupta, 167–68. ↩︎

-

97

Jan Zita Grover, “Constitutional Symptoms”, in Taking Liberties, ed. Carter and Watney, 152–53. ↩︎

-

98

Ibid., 154. ↩︎

-

99

Lowe, interview. ↩︎

-

100

Nicholas Lowe, “The Photographic Commission: Doing Life”, in Living Proof, ed. Lowe and McMillan, 52. ↩︎

-

101

Ibid., 53. ↩︎

-

102

Lowe, interview. ↩︎

-

103

Nicholas Lowe, “Interview with Angela”, in Living Proof, ed. Lowe and McMillan, 37. ↩︎

-

104

Lowe, interview. ↩︎

-

105

Lowe, “The Photographic Commission: Doing Life”, 52. ↩︎

-

106

Ibid. ↩︎

-

107

Lowe, interview. ↩︎

-

108

Lowe, “The Photographic Commission: Doing Life”, 56. ↩︎

-

109

Stuart Marshall, “Picturing Deviancy”, in Ecstatic Antibodies, ed. Boffin and Gupta, 21. ↩︎

-

110

“The Photographic Workshops: Lynne Otter”, in Living Proof, ed. Lowe and McMillan, 89. ↩︎

-

111

Nicholas Lowe, “The Photographic Workshops: The Workshop Plan”, in Living Proof, ed. Lowe and McMillan, 68. ↩︎

-

112

Ibid. ↩︎

-

113

“The Photographic Workshops: Keith Livingstone”, in Living Proof, ed. Lowe and McMillan, 93. ↩︎

-

114

Ibid., 93. In the book Living Proof, this work is attributed to Keith Livingstone and Nicholas Lowe. It was used as the cover image for the book and the flyer advertising North East AIDS Week. It was part of the national Billboard Art Project led by the BBC and the Radio Times in May 1992 and was included in the exhibition Fatal Attractions: AIDS and Syphilis from Medical, Public and Personal Perspectives at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine in May 1995. ↩︎

-

115

Grover, “Constitutional Symptoms”, 155. ↩︎

-

116

Lowe, interview. ↩︎

-

117

Kate Davy, “Fe/male Impersonation: The Discourse of Camp”, in Critical Theory and Performance, ed. Janelle G. Reinelt and Joseph R. Roach (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992), 231–32. ↩︎

-

118

Lowe, “Who Needs a Prosecution to Make a Point?”, 157. ↩︎

-

119

Cheng, Juhasz, and Shahani, “Introduction”, 4. ↩︎

-

120

See Valerie Corris et al., “Health Inequalities Are Worsening in the North East of England”, British Medical Bulletin 134, no. 1 (2020), 63–72. ↩︎

-

121

See Joyce Liddle, John Shutt, and Cameron Forbes, “Levelling Up or Down? Examining the Case of North-East England”, Contemporary Social Science 18, nos. 3–4 (2023): 469–84. ↩︎

-

122

Román, Acts of Intervention, xxiv. ↩︎

-

123

Gareth Longstaff, “‘He Had a Pair of Shoulders Like the Tyne Bridge’: Queer Evocations of the North East and the Legacy of Out on Tuesday and Out”, in Locating Queer Histories: Places and Traces across the UK, ed. Matt Cook, Alison Oram, and Justin Bengry (London: Bloomsbury, 2022). ↩︎

-

124

Eric Stanley, in “Dispatches on the Globalization of AIDS: A Dialogue Between Theodore (Ted) Kerr, Catherine Yuk-ping Lo, Ian Bradley-Perrin, Sarah Schulman, and Eric A. Stanley”, in AIDS and the Distribution of Crises, ed. Cheng, Juhasz, and Shahani, 38. ↩︎

Bibliography

Basement Group, Projects UK and Locus+. This Will Not Happen Without You: From the Collective Archive of the Basement Group, Projects UK and Locus+ (1977–2007). Sunderland: University of Sunderland Press, 2007.

Boffin, Tessa, and Sunil Gupta. “Introduction”. In Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology, edited by Tessa Boffin and Sunil Gupta, 1–5. London: Rivers Oram Press, 1990.

Bolton, Richard, ed. Culture Wars: Documents from the Recent Controversy in the Arts. New York: New Press, 1992.

Campbell, Beatrix. Goliath: Britain’s Most Dangerous Places. London: Methuen, 1993.

Cheng, Jih-Feh, Alexandra Juhasz, and Nishant Shahani, eds. AIDS and the Distribution of Crises. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020.

Cheng, Jih-Feh, Alexandra Juhasz, and Nishant Shahani. “Introduction”. In AIDS and the Distribution of Crises, edited by Jih-Feh Cheng, Alexandra Juhasz, and Nishant Shahani, 1–28. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020.

Cifor, Marika. Viral Cultures: Activist Archiving in the Age of AIDS. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2022.

Colls, Robert. “Born-Again Geordies”. In Geordies: Roots of Regionalism, 2nd ed., edited by Robert Colls and Bill Lancaster, 1–33. Newcastle upon Tyne: Northumbria University Press, 2005.

Colls, Robert, and Bill Lancaster, eds. Geordies*: Roots of Regionalism. 2nd ed. Newcastle upon Tyne: Northumbria University Press, 2005.