Revisiting Loss of Heat through Intergenerational Collaboration

Revisiting Loss of Heat through Intergenerational Collaboration

Interview by Beth Bramich With Noski Deville And Nicola Singh

Abstract

In this conversation, Noski Deville and Nicola Singh reflect on their recent collaboration to craft a contemporary response to Deville’s film Loss of Heat (1994). They describe their working processes and how they created new artworks that respond to the restoration, preservation, and screening of Loss of Heat by Cinenova in 2022. With their interviewer, Beth Bramich, they discuss embodied aspects of film and intergenerational collaboration, and explore the possibilities of combining film with sound art, written and spoken text, and live performance. They consider the political contexts surrounding the release of Loss of Heat in 1994, its screening in 2022, and its depictions of queer love between British South Asian women and of the lived experience of the invisible disability of epilepsy.

Introduction

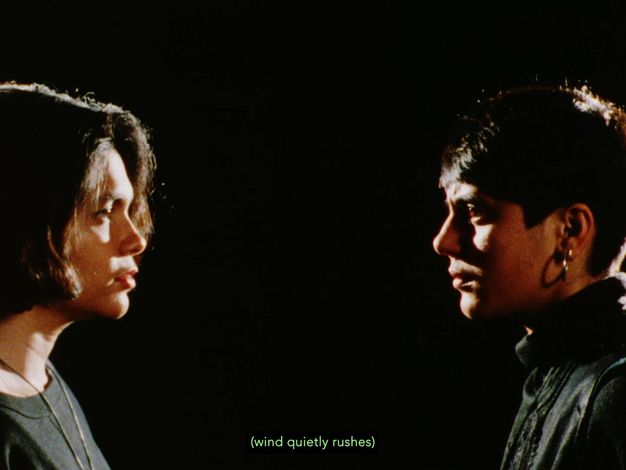

In January 2024 I met with the film-maker Noski Deville and the performance artist and experimental vocalist Nicola Singh to discuss their experiences of exploring the film Loss of Heat and its contemporary resonances through an intergenerational collaboration (fig. 1).1 Singh had been commissioned in 2021 by Cinenova, a volunteer-led charity based in London that distributes and preserves feminist film, to create new work in response to Deville’s film.

1

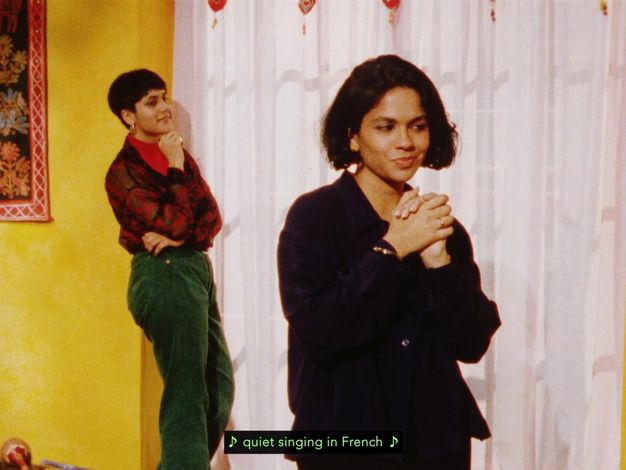

Loss of Heat challenges preconceived notions of white, ableist heteronormativity by centring queer love between British South Asian women, and the lived experience of the invisible disability of epilepsy. Cinenova describes the film as a “poetic, immersive interpretation exploring the interplay of the emotional and the physical, across boundaries of sexuality, dependence and desire”.2 Loss of Heat had been newly digitised and captioned as part of its international touring programme “The Work We Share”, alongside nine other films from Cinenova’s collection addressing representations of gender, race, sexuality, health, and community, which had been selected for the precarity of their material condition. New responses by contemporary artists and writers were commissioned for each film to encourage a dialogue across time and space.3

2Singh’s response to Loss of Heat developed into a collaboration between artist and film-maker, as they shared questions, reflections, and memories that led to a sonic improvisation between Deville on saxophone and Singh vocalising. This sound work became a live performance staged at Brighton Centre for Contemporary Art in 2022, and a studio recording set for release in 2025. Our discussion explores the meanings of Deville’s film today through this exchange of practice and what it suggests for the possibilities of revisiting film and film histories.

Following the work of Sharon Hayes on strategies of historical return, my approach to oral history centres on intergenerational dialogue as a means to expand understandings of the creative practices and social contexts of film histories.4 Inviting practitioners and their collaborators into a process of storytelling and reminiscence in relation to a film can make collective space for critical reflection on (dis)continuities between the past and the present. This can be particularly useful for contributing to histories that have been partially obscured by censorship and marginalisation, or that have been limited by categorisations that ignore their inherent intersections.

4Opening Up a Space for Collaboration

Beth Bramich: My interest in your collaboration stems from seeing your performance and being struck by how you tapped into the sensory and emotional resonances of the film—I’m keen to discuss your approach in terms of a revisitation of a historical moment and the ethics of this form of collaboration. Could we start by exploring the process that led to the performance and your experience of making new work together in response to Loss of Heat?

Nicola Singh: I was gassed to be approached by Cinenova because I really respect them and what they stand for in their ethics and choices. I had one previous experience of responding to a film by performing in a screening context, and thought a lot then about the tensions between bodies on screen and bodies in real life. My first question was how it would be possible to give audiences an embodied experience connected to the themes of Noski’s film and the tactility and touch it expresses. How might it be possible to extend that sensibility and atmosphere beyond the film or to heighten, enhance, and add to it? My first idea was to make a sculpture, a semi-precious quartz stone that could be offered to audiences to hold during or before or after they had watched Noski’s film. Particular semi-precious stones are cooling to the touch. This sensation would go some way to representing the physiological effects of the epilepsy experienced by the character in the film.

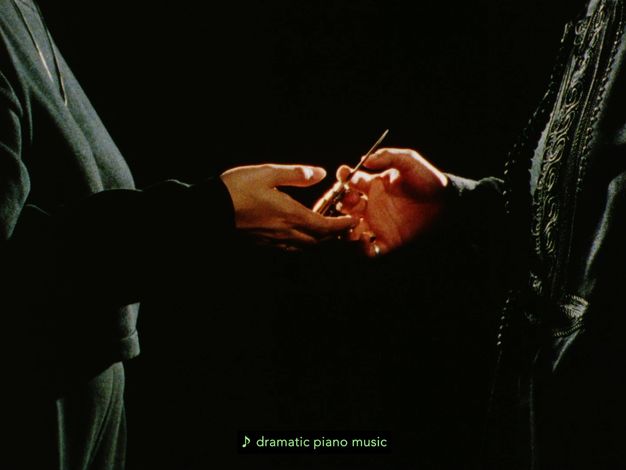

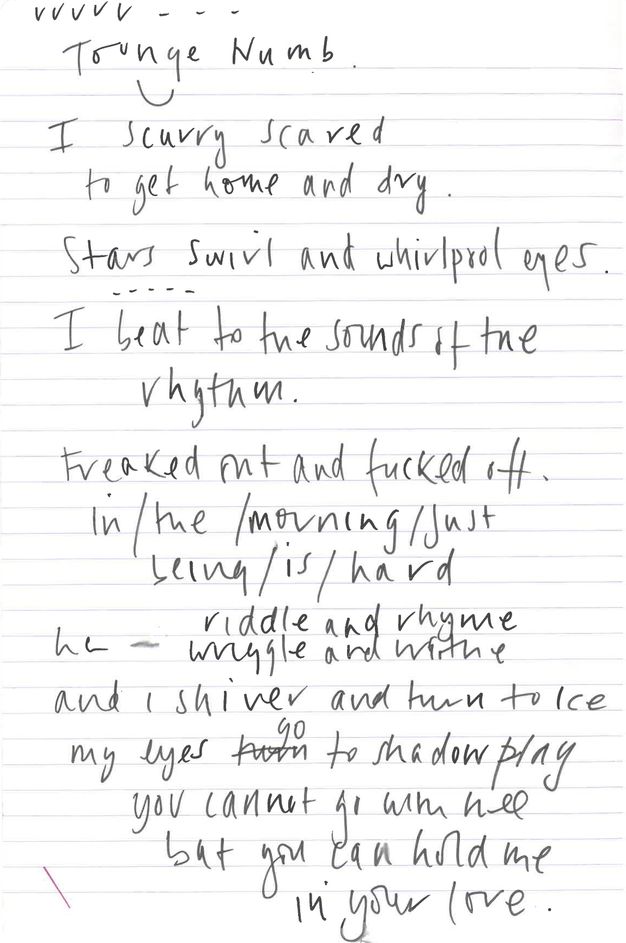

After my first conversation with Noski, I saw that we had space to collaborate organically because of our shared natures. I felt this enthusiastic openness in her to talk about the work, revisit it, and think about it in detail. After I heard Noski speak about her relationship to the film’s soundtrack, about her use of language and poetry, and about the cast, we started gathering ideas. My idea was that we would work with a short text that she had written during the genesis of the film. I was really struck by the different sounds, temperatures, and textures in the text. It’s a rich piece of work, which held lots of potential for my own practice of working with text through experimental improvised vocals. I thought, let’s find this text through the medium of sound/song, in a slippery space in between. Because Noski plays saxophone, it seemed natural that we might meet with these two instruments (figs. 2 and 3).

BB: I think it was inevitable I would compare my experience of the studio recording to the performance at Brighton CCA. The improvisation between Nicola’s vocals and Noski’s saxophone has the same themes but unfolds in subtly different ways. I listened to it a few times to try to separate out some of those feelings. In the live performance you seemed to push each other more, to play with distance and build-up, perhaps with the adrenaline of being in front of people, and you used the space around both of you to physically add to that through movement, while in the recording you both feel more immediately present and spatially closer together. I was imagining the improvisation happening between you as you caught each other’s eye.

Noski Deville: Your response makes me feel better about our choices because people are mostly going to engage with the sound work in a more intimate way. I think that closeness in the recorded studio version, in conjunction with the text they can read, is very effective. Performing with the audience felt different. It’s something we gave a lot of thought to, as recordings of live performances can often be a bit flat, more like documentation than engaging with you spatially and sensually. But as you said, Nicola, our evolving journey together felt very creative and enjoyable, and responsive relationships were an anchor for both this project and the film—partly because we’re talking about the body, physicality, disability, and the sanitisation of those things. This came up at a screening event at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in 2022 where Christie Costello from the Bare Minimum Collective spoke with Lola Olufemi about the programme “The Work We Share”.5 They discussed how we get outside of ourselves and disabling power structures through our connections with others. Lola went on to say that, because Loss of Heat aimed to share an experience, it takes us into an almost out-of-body experience. So there’s disconnection, connection, and interconnection going on.

5The short text Nicola mentioned captures when I began to explore wanting to share that experience. In my notebook I wrote about key images, but it’s not over-theoretically thought out. I knew I wanted to show a sunflower field, for example, and I remember someone saying there’s some in Wales. But then one of the cast members, Valentina Gomez-Martinez, had a mum who lived in Spain, right by sunflower fields (fig. 4). We did a very cheap and cheerful escape there, with minimum kit. That was the start of the film-making.

I’d put an application into the Arts Council and didn’t know if I was getting money or not. And much of the script was created on set, as we had made time to collaborate and work together. Some of the stories woven in are experiences from the actresses’ childhoods. When Anjum Mouj talks about taking bolts out of a bench in the film, that’s one of her memories, not mine. I chose not to include stories from my childhood because that’s a whole other complex thing. But we spent time together talking and exchanging. Sharing is really key to that way of working. It was always fluid, respectful, and responsive, a very genuine process in creating an experiential piece rather than narrative fiction. Although it has narrative form, it is also about accessibility and a way of communicating.

NS: Our project was a massive journey. The text was edited and expanded, and then became shorter again. And we experimented with pulling particular words out, at one point sticking them on Post-It notes around the rehearsal room at Cafe OTO, and thinking together: What’s the right order? What’s the arc? Where are we going? How does this feel? The way I approach language is pretty intuitive, playful, and curious. I thought about splitting up words and their sounds and each word and its meaning. There’s a lot of repetition, which allows for meaning to change or shift, and the repetition ends up creating atmosphere and feeling that you can then punctuate or pop with the next sound. It’s a bit like letting your body become a channel for the language, its sound, and its meaning (fig. 5). It takes a particular type of attention and listening modality, where one is able to utter a sound, listen to that sound, receive it, and then make the next sound. Maybe all improvisers would describe their practice like that. That rehearsal room is like a little cave, so it was intimate—plodding around this dimly lit space together. I move around a lot when I sing because it helps. At points it felt like we were following each other, or chasing or spinning around each other and all this furniture and leftover junk in there. I have really warm memories of that.

BB: Could you speak more about how you imagined your rehearsals at Cafe OTO would translate to performing in front of an audience and how the screening space might change the dynamic of the improvisation?

NS: We were making two pieces, thinking about the live performance and the Cinenova website as an online digital repository for the work. The curator at Brighton CCA, Polly Wright, is amazing and gave us really thorough images and information about the performance space, which was an institutional theatre space with raised seating, a stage, and curtains—a pretty traditional, dry performance space. Noski and I started by sending recordings to each other because we couldn’t meet in person. When we finally could be in the same city, everything naturally got up on its feet. The physicality, the dancing, the movement—that’s so natural when I’m vocally improvising, although it’s taken me a while to let that be available in a live context, because sometimes nerves keep me from moving as freely.

One of the reasons I make the kind of work I make, and why I felt such a connection to Noski’s film, is because of how it can put you into your body but also encourage you to go beyond its materiality. I think about that a lot with making and singing. How it can ground you and also help you just let go of your body as well. Making this kind of work has the possibility of being quite transcendental—and also healing. And, of course, those themes are very present in Noski’s film. Cinenova made a really good choice bringing us together—Noski and I work with similar processes, feelings, and themes through different registers of film-making and live performance.

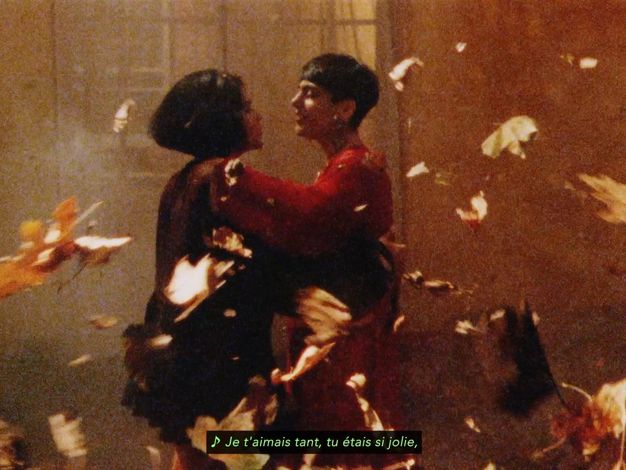

ND: Yes, I was really chuffed to be invited to collaborate with you and also mindful that it’s your commission. One of the things that emerged in rehearsal was a certain embodiment, which then started to relate to how the audience would transition from the film to the performance. Illuminating a mirrorball, which was an existing feature of the theatre space, threw slowly shifting dappled light that recalled the film’s end dance scene, which is sensual and transportive (fig. 6). We wanted to continue that experience, or extend it, by transitioning from the film into the performance, rather than for the film to end and then lights up and back to reality. The mirrorball gave a pre-emptive note of readiness for the audience to start going on the next part of the journey.

BB: As the film ended, I was still resonating with the tensions and intimacies of the couples’ relationships, which was then held and expanded by what you were doing with your voice, Nicola, stretching and building sound, and then Noski and the saxophone arrived in the performance. It was a bit like a magic trick.

NS: For me, the mirrorball effect became a poetic metaphor for various elements of how I experienced the film. The dappled in-betweenness of the light could refer not only to a sensory experience of epilepsy, but also to the natural shifts and swirls between the lovers and to a viewer’s experiences of space and time within the film. We also used this effect to shift the live audience’s experience of the architecture from a screening space into a performance space. Using the mirrorball seemed like a way we could pick the audience up and take them back into the work through light and kinetics. Then, purposefully, we could take up the space of the stage, where the projection had been just before. We thought about the choreography and how we might structure things quite a lot, and we made a few markers, one being that Noski would arrive through the same entrance the audience had done earlier in the evening. The sound came behind the audience as a surprise but also as something growing and coming more and more into the centre of the stage.

Captioning the Film

BB: Another aspect of Loss of Heat being included in the programme “The Work We Share” was that the film had been newly digitised and new captions had been created by Collective Text (figs. 7 and 8). I understand that you were involved in the captioning process. Can you share something about this experience?

ND: Nicola and I were working together before the collaboration with Collective Text started, and we carried on long after that screening to refine it further.6 I really enjoyed working with Collective Text and they pushed me to think about how you communicate a soundscape with words. I think a lot of people don’t understand it’s a creative process—subtitling, captioning, describing audio. It made me think more about the film and what I was trying to communicate at different points. Sound, especially abstract sound, can get lost in translation. It’s a process that is very much about film from a user’s perspective, and it’s another language to learn: how to describe feeling on a sound basis—When is it scratchy? When is it gritty? It’s like translating a poem from one language to another. You have the same concerns about whether the feelings get overwhelmed by the nuts and bolts.

6NS: I actually had no relationship with Collective Text besides speaking to Noski a little bit. But when we worked with Noski’s notebook text—as we rehearsed—it was quite a natural process of coming to the clearest and most efficient arrangement of the words. I was thinking about what the text will cue in terms of meaning and of aesthetic and sonic information. I wanted the audience to feel invited into the work because, for me, too much information, especially text, throws me right out of an experience. I always want to find this balance. And we were playing with the words and their meanings so much, even though Noski is on the saxophone. Still there’s melody and line and phrase passing back and forth. The audience might still hear a word reverberating within the voice of the saxophone after I’d put it up in my voice.

BB: It seems really important that you had time to explore this, drawing on how Noski’s writing and film captured a personal experience through a visual and embodied language as a focus for reinterpretation and translation. This seems to have informed your collaborative process, and your motivation to keep the resonances of the film going after the final image had faded.

NS: We did have a lot of time together. We got straight into exploring the film in musical, or sonic, terms. And in between these musical exchanges, there was storytelling from Noski around different memories that came up. I’m glad that, rather than there being a research phase and then a research through music phase, they were blurred. In my experience, collaboration often does take ten times longer than working by yourself. It was a labour of love but a labour nonetheless.

I remember distinctly that, in our first conversation, Noski and I both said we were quite slow. I guess sometimes “slow” is used as a derogatory term, but it does takes time for things to germinate or settle or land. From my experience, that’s because they’re landing not just in my brain but elsewhere too. Thoughts and emotions take different amounts of time to settle and to become things you can express with someone. Because Cinenova knows these things, there was a good amount of lead-in time. It’s really annoying when organisations ask you to make a new piece of work and give you, like, two months. The responsibility of responding to someone else’s work was also quite present for me. It didn’t weigh me down but it was something I was mindful of. All the way through, I asked Noski questions about her process, her relationship to the people in the film, her embodied experience, and the film’s history, which would then feed into my response. The work grew as our friendship grew. As part of that, I felt really excited to reactivate this queer space that was also connected to a British South Asian lived experience.

Looking for Intersectional Forms of Representation

BB: I’ve been reflecting on the moral panic in the 1980s and 1990s that led to legislation like Section 28 and the self-censorship it encouraged. Noski, were you thinking about this, and the possibility for intersectional forms of representation, by bringing disability, queerness, and British South Asian experience together?

ND: I remember seeing how long Section 28 was actually around for, from 1988 to 2003. We’d all been through a lot by the time this film was being made, including losing lots of friends. What you’re seeing with Section 28 is an institutional response to that perceived risk and threat. It’s definitely interlocked with issues of representation as well. The film was about personal experience, mine and my friends’, and being aware that those things weren’t on screen. I looked at a quote from Audre Lorde, “It is not our differences that divide us. It’s our inability to recognize, accept, and celebrate those differences”. How does that cross over? Because, in terms of epilepsy, one kind of feedback I got is that I’d made it almost sexual in places and therefore almost desirable. These things have a tension and aren’t comfortable. But that’s a fairly honest reflection of most people’s worlds. When the film speaks to somebody maybe it is because there’s an understanding of how we experience the world and our friends, our lovers. And I think intergenerational exchange is really exciting because it’s too easy to have division rather than interest, curiosity, and sharing. That’s why the collaborative process is exciting as well, because I don’t see the world in single strands. It’s a much more intertwined place for me.

BB: And Nicola, what was particularly exciting for you about the representation of British South Asian women in a queer context?

NS: It is still refreshing and revitalising to see two brown lesbian women, queer women on screen (figs. 9 and 10). And I watched this film first only a couple of years ago. That’s mad. There was, and still is, a serious lack of representation. One of the things that did stick in my head was learning about Section 28 when I was about thirteen or fourteen and having a conversation with my dad about it. And then seeing My Beautiful Laundrette—I was maybe seventeen or eighteen—and understanding it was made in 1985 and it was the first time there was an interracial gay male snog on screen, an allusion to sex on screen—and that blowing my mind. I mean, it’s a fucking amazing film, severely sublime, that so directly deals with racism. But the fact that there are so few examples is desperate. You have to be in privileged spaces even to access these films because they’re not in the mainstream at all.

ND: There’s a pinch of My Beautiful Laundrette influencing my film in some way, shape, or form. It was so important to me and my friendship group. But it does sort of stand in isolation. Things have moved on, but there are still not as many of those moments you dreamt there would be, when you were young and fighting. It’s interesting, considering levels of specificity when casting. I thought about that when I was learning about film and film-making. If we read a novel, watch a film, or listen to a piece of music, at its best we can inhabit part of it and go on a journey with it. The way I looked at it at that point was it’s not singular; rather, there’s a lot of shared experience. I probably would rethink that now. When I made Carousel, a more experimental short film, at the London Film-Makers Co-op, I put an interracial lesbian kiss in there, after learning about the strict regulations and censorship of such relationships that had been in place for decades in Hollywood under the Hays Code.7 Even an unmarried kiss could be shown only if one foot was kept on the ground. I remember Miles Davis talking about going to Paris in 1949 and being able to have an interracial relationship openly with Juliette Greco and the freedom of being able to walk around Paris holding hands. You’re aware of a history of censorship. Growing up, you know that your world, your friends’ worlds, are not being shown. I just think it’s incredibly sad it’s not as far on as it should be. All those battles, Section 28, supporting the miners, Rock Against Racism, all of that. We’ve still got a long way to go.

7NS: And, because you’ve got me thinking, Beth, when you were saying about the effect of Section 28 on self-censorship over decades, what psychically is going on there? That also extends to this conversation we’re having about seeing people of colour and interracial relationships on screen. I know, as a child of an interracial relationship, that not seeing that actually deeply affects your ability to self-actualise. This is not an original thought—people in racial studies have talked about this for years—but it’s a really fundamental thing. It gets right deep inside you. Now, culturally, we have become more cognisant of what it means to represent someone else’s experience, and the complexity and mutuality of experience and identity. But it is possible to make collaborations that explicitly, as well as within the fabric of the artwork, out the different contextual privileges and that offer in-between spaces. For someone who exists in a bit of an in-between space like me, it feels important.

ND: There should be room for it to be more fluid because that singularity is actually a bit of a myth. I’ve spent my time collaborating and working with others and supporting other stories being told. But I don’t know exactly how I’d approach that now. It takes a lot of time and space to make work like that together.

NS: It’s about really eyeing the processes we choose, understanding what ethics are implicit in the decisions we’re making, be they creative or about material resource, because it all figures and prefigures what’s possible and who can be involved in those different things. It takes a long time and loads of concentration. I keep coming back to Cinenova. As an artist who works with them, I feel that they understand this. It’s why Noski and I have been able to take the time we have and feel quite free to not know what was unfolding or how it might materialise. I’m really grateful for that.

ND: That’s really important—that we had room to explore and to not know. There’s a pressure to act like you know everything. You see a great upbeat British film like Pride, about supporting the miners’ strike.8 That captured some of the huge collaborations and shifts going on. I think you can see that Section 28 was a response to AIDS but also to the different communities that were starting to work together against division and censorship, alongside the union structure that was being broken down. It’s all interrelated. I think it’s hard with or without Section 28. We’ve lived through times of demonisation, of being attacked, and you’re aware how easily it can come back again.

8BB: There are conversations in groups I’m part of right now about how anti-trans bills and policy seem to reprise the aims of Section 28, preventing discussion, support, and representation, by targeting educational spaces. They seem to know how effective it is to stop those forms of, as Nicola put it, self-actualisation.

ND: The pressures that have been put on education for quite a long time have had a massive effect. In truth there’s a lack of accessibility, enablement, and inclusivity in how restrictive and formulaic it has become. It’s not just about young people having to live with a huge debt but also that they’re not being given the time, space, and openness to learn and develop.

NS: There’s something I hope it’s useful to add about these cross-cultural conversations—Section 28 and its effects or even just a consciousness around queer, gay, lesbian experience. For those of us living a British South Asian experience and a queer British South Asian experience, and I can only talk of my own experience, the speed or the consciousness with which these ideas move through cultures are different and come up against different kinds of challenges. As an individual, you’re moving a little bit in different directions or speeds, which provokes particular behaviours or coping mechanisms or negotiations.

BB: My mother was somewhere between a first- and a second-generation migrant from Burma via India, and in some ways it raised some questions in my thinking. Burma (or Myanmar) was not often in the news but it was mentioned in Amnesty International magazine, one source of my still really potted historical understanding of the country’s political landscape. Even having a small awareness of different perspectives from the mainstream opened up something about whose stories got to be told.

Working Intergenerationally, Revisiting, and Archiving

BB: The time you put in to develop your collaboration, and together to find ways through the film, fed into how the new works were realised. Perhaps we could call that a method of revisiting or facilitating revisiting. With the wider themes of this British Art Studies special issue in mind, could you share something about what your journey could offer other artists and film-makers, as well as historians and curators?

ND: You raise this issue of experiencing otherness. Epilepsy is other, queerness is other, racial identity—all of these things are othered, and there are shared crossovers. It can make us more open but is also complicated to navigate. For better or worse, it is still relevant; there are still things people are recognising, engaging in, and exploring. Generating new responses, expanding and exploring—that’s really healthy. At the moment in the jazz scene, Tomorrow’s Warriors and the Nu Civilisation Orchestra are revisiting amazing stuff and producing incredible collaborations that create a whole new, very valid, life for those works.9

9In terms of my film, in some ways it was put behind me as I moved forward with my life. It’s interesting to stop and think about that. I think revisiting is really important at lots of levels and interlinks with when we don’t see ourselves or don’t have points of recognition that help support us. I can remember, when I was young, interrailing and landing up in a bar in Amsterdam and seeing these two older women together at the bar, and it was just this really joyous moment, a simple validation. As I said at the event in Brighton, over one in ten people will have some form of epilepsy or other in their lifetime, and it’s still such a taboo subject. Notions around disability, and especially around invisible disability, are still vital to explore and be seen and talked about more.

NS: I was actually going to say that in our conversation we’ve possibly given more weight to representations of ethnic racial identities than we have to the intersection of those with the experiences of living with epilepsy and invisible disability.

ND: Yes, at the core of the film it is a representation of an experience of living with epilepsy. It’s a mixture of things, including people’s fear of it, and historically there’s revulsion. The film opens with a Dostoevsky quote: he described his epileptic euphoric moment, this sort of super-high as he entered a fit.10 Things aren’t singular in that way. It is important to look back, but it shouldn’t just be an archive. An archive is great and useful, but I don’t know if there’s such a thing as a live archive. We go to see classic films again, we revisit work, and in that process there’s a reinvention and new things come out of that.

10BB: When we’re historicising and focusing on certain kinds of interpretations, we might want to bracket time periods as if there were no continuity or overlap between experiences, but your collaboration suggests a need to understand how the landscape sits together intergenerationally. In revisiting, we may be able to attend to these complexities. Maybe that’s what the liveness of the archive means?

NS: I was thinking what also really matters is how we revisit. The question you had about what this work offers historians hopefully also asks for a different kind of research and historical relationship to the work, even in the cycle of revisiting. Beth, you were at the live performance and you’ve engaged with documentation. It’s not a distanced reading of the work: it’s quite a close-by, intimate experience. And, as I understand it, you also have lived experience that relates entirely to some of the themes being passed around. I guess quite often in academia, in history—because those are positions of some privilege—people are writing about things not related to their lived experience at all, and they become extracted and instrumentalised.

I think what we’re doing here is modelling what feels like better ways of doing things. And also what we’ve left behind is a work, which I hope really asks you to feel and to be situated because that was also my experience of Noski’s film. This work, this collaboration, could encourage different ways of researching or historicising experience. Cinenova set that template for us by making an initiative for this incredibly important work, finding the funding, and then offering a new responsive platform for artists where lived experiences resonate. They put this programme together to preserve, to provide new interpretation, to generate cross-generational conversations, and to allow all these concepts to bubble up. And it makes me wonder whether they should be part of a conversation around the work as well.

ND: I think it’s really important because it’s not linear or singular. These processes of revisiting and reworking are possible and also, within that, there’s a kind of hope. You can have an impact and it can re-impact or resonate later. That’s a very positive thing. I’m glad the film still has a voice.

Acknowledgements

Preliminary research for this interview was first presented at the conference “Women in Revolt! Radical Acts, Contemporary Resonances” at Tate Britain in 2024, in the session “Devolved Screens: Alternative Approaches, Changing Content”, chaired by Lauren Houlton. I would like to thank Noski Deville and Nicola Singh for their generosity in sharing their reflections on their collaboration and friendship. I would also like to share our huge appreciation for the Cinenova Working Group and its commitment to the support of and advocacy for the artists, writers, and film-makers represented by and working with their collection, and the ongoing preservation and presentation of the collection to new audiences; and give thanks to Polly Wright for producing Noski and Nicola’s live performance at Brighton CCA. Finally, I would like to thank the special issue editors, the editorial team at British Art Studies, and the peer reviewers for their generous feedback and productive suggestions.

About the authors

-

Beth Bramich is a writer and researcher. She is a senior lecturer in fine art at Camberwell College of Art and a PhD student at the Screen School at London College of Communication, University of the Arts London. She is part of the London-based, queer-led, all genders community choir F*Choir and a working group member for the Feminist Duration Reading Group, currently in residence at Goldsmiths CCA. She holds an MA in critical writing in art and design from the Royal College of Art.

-

Nicola Singh is a British Punjabi artist working across performance art, experimental new music, visual art, and somatics. She explores the subjective and socially determined complexities between voice and body and the ways in which language compounds/disorients this relationship. Her practice also incorporates film, drawing, and movement practices. Selected commissions include SPACE STUDIO (India), the Tetley (UK), Cinenova and Brighton CCA (UK), David Dale Gallery & Studios (UK), WORKPLACE (UK), Eastside Projects (UK), Hong-ti Art Center (South Korea), Jerwood Arts (UK), and Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art (UK). She has been resident artist at Porthmeor Studios (UK), La Bonne (Spain), Hospitalfield (Scotland), and the Art House (UK). Her work was acquired by the Government Art Collection in 2021. Nicola is an associate artist with Migrants in Culture and a board member of Ubuntu Women Shelter, Glasgow. She has a practice-led PhD in performance writing from Northumbria University, and teaches internationally. Nicola was awarded the Multidisciplinary Fellowship for 2025–26 by the Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation.

-

Noski Deville is a cinematographer and film artist working across film, music, and sound. As workshop coordinator at the London Film-Makers’ Co-op in the 1980s, she developed her skills on the JK Optical Printer. With over twenty-five years’ experience as a cinematographer, Deville is well known from her award-winning work with internationally acclaimed artists, including Isaac Julien, Steve McQueen, Alia Syed, Daria Martin, and Jananne Al-Ani. In 2015 she won the Jules Wright Prize for her cinematography in the field of visual arts. An industry-recognised director of photography and member of the Guild of British Camera Technicians, Deville is also a committed film educator, having headed up the cinematography department at the University for the Creative Arts Farnham Film School.

Footnotes

-

1

Loss of Heat, directed by Noski Deville, 1994, 20 min. ↩︎

-

2

Cinenova, “Online and In-Person Events. 28 Apr–30 Apr 2022”, https://cinenova.org/event/the-work-we-share-loss-of-heat-at-brighton-cca/. ↩︎

-

3

Documentation of “The Work We Share” programme can be accessed at https://cinenova.org/project/the-work-we-share. ↩︎

-

4

For her approach to historical return see Sharon Hayes, “Temporal Relations”, in Not Now! Now! Chronopolitics, Art & Research, ed. Renate Lorenz (Vienna: Sternberg Press, 2014), 56–71. ↩︎

-

5

Christie Costello and Lola Olufemi were invited to respond to a screening of three films from Cinenova’s “The Work We Share” programme, including Loss of Heat, A Song of Ceylon (1985) by Laleen Jayamanne, and A Prayer Before Birth (1991) by Jacqui Duckworth, as part of the Essay Film Festival, 19–20 March 2022. ↩︎

-

6

Collective Text is a Glasgow-based worker collective specialising in creative captioning and audio description for art and experimental film, which shares skills and expertise to deliver intersectional access projects. More information about the work of Collective Text can be found at https://www.instagram.com/collectivetext and https://linktr.ee/collectivetext. ↩︎

-

7

The Motion Picture Production Code, known as the Hays Code after its creator Will H. Hays, set out restrictive guidelines that directly influenced the content of films produced in the United States between 1930 and 1966. ↩︎

-

8

Pride (2014), directed by Matthew Warchus. ↩︎

-

9

Tomorrow’s Warriors, founded in 1991, is a British talent development organisation, creative producer, learning and training provider, consultancy, and charity specialising in jazz. The Nu Civilisation Orchestra is its professional orchestra, founded in 2008 by its artistic director, Gary Crosby OBE, and led by its musical director, Peter Edwards, which has toured the United Kingdom extensively, developing ambitious and collaborative creative reimaginings of works such as Stravinsky’s Ebony Concerto, Joni Mitchell’s Hejira, Duke Ellington’s Sacred Concerts, and Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On. More information is available at https://tomorrowswarriors.org. ↩︎

-

10

“All you healthy people don’t even begin to understand what happiness that we epileptics experience during the instant before an attack. I don’t know whether that bliss lasts seconds or hours or months but believe me, I wouldn’t exchange all the joys life can offer for that bliss!” The quotation in the film has been adapted from Sofya Kovalevskaya’s record of a private conversation with Fyodor Dostoevsky, published as A Russian Childhood (1889), and quoted in Louis Breger, Dostoevsky: The Author as Psychoanalyst (New York: NYU Press, 1989), 249.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 14 July 2025 |

| Category | Interview |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-27/bbramich |

| Cite as | Bramich, Beth, Noski Deville, and Nicola Singh. “Revisiting Loss of Heat through Intergenerational Collaboration.” In British Art Studies: Queer Art in Britain since the 1980s (Edited by Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, Theo Gordon and Laura Guy), by Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, Theo Gordon, and Laura Guy. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-27/bbramich. |