Rewriting the Future

Rewriting the Future: Tessa Boffin’s The Knight’s Move

By Flora Dunster

Abstract

This article focuses on the practice of the late photographer Tessa Boffin. I situate her work in the context of British art and politics as they were at the time of “queer” being reclaimed from a term of abuse in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and explore how she used photography to visualise what “queer” could mean from a lesbian perspective. The article centres on an analysis of Boffin’s series The Knight’s Move (1990), in which she rewrites the history of her queer present to include a lesbian past. While these photographs can be viewed as a precedent for an intersectional and exploratory understanding of queerness, I suggest that “the knight’s move” can also work beyond the series itself. I locate it as a strategy for bringing “queer” and “lesbian” together in our present, re-figuring both positions in relation to each other and in resistance to the gatekeeping around the meaning of each word. I argue for the knight’s move as a device that allows us to situate photographs not as historical remnants but as a vital site of community formation, thereby offering a way of working with Boffin’s oeuvre rather than on it.

Introduction

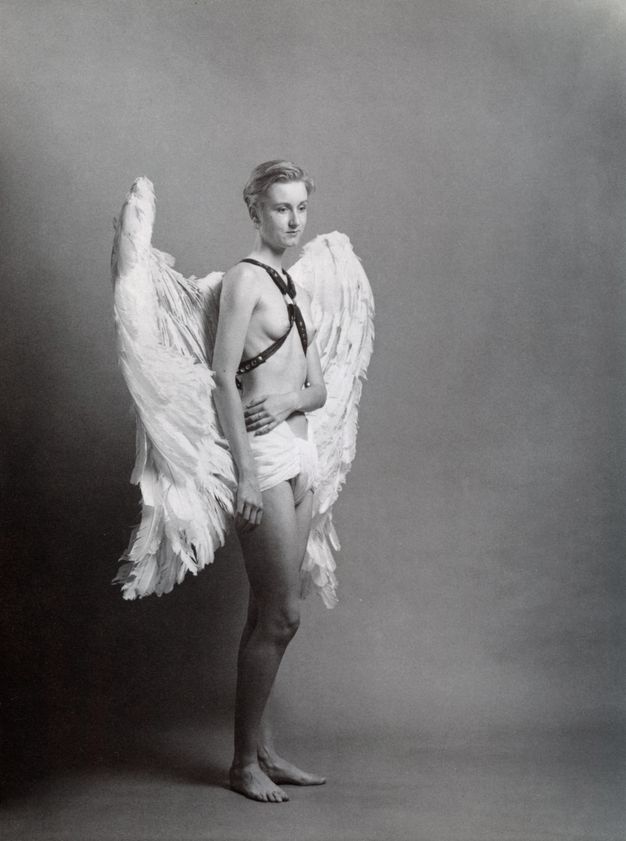

Towards the middle of Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser’s 1991 book Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs is an angel. She stands alone on a full page, clad in a loincloth and strapped into a leather bondage harness, the back of which—obscured by the angle of her pose—supports the large white feathered wings that curl around her (fig. 1). With one arm gently draped across her stomach, she turns her gaze towards the lower corner of the frame.

This angel has long struck me as a Benjaminian figure: melancholy as she stares down the catastrophes on which her present has been built and that are repeated when we mistake the wreckage left behind as a necessary by-product of progress. An angel of lesbian history, perhaps, who understands how this wreckage forms the basis of our present and how it might yet change our course.1 Photographed by Boffin as part of her series The Knight’s Move (1990), the angel and her compatriots—a knight, a knave, a lady-in-waiting, and a Casanova—illustrate the desire for a more complex picture of lesbian history, one that works against the erasures wrought by heteropatriarchy. But they also underline an ethics that is braided into a methodology for “doing” lesbian history. This is named by Boffin in the work’s title. The knight’s move allows us to tangle time, toggling between moments as we navigate ourselves towards a future, not by charging forward but by making the urgencies of the past our own.

1Stolen Glances is an idiosyncratic collection, which assembles lesbian photography alongside a selection of essays, poems, and reflections (some purpose-written, others republished from elsewhere). Together, these contributions seek to undo the idea that “lesbian” has a fixed meaning, instead picturing it through a multiplicity of intersecting identities and refining its use by relating it to different forms of lesbian subjectivity. The Knight’s Move is just one way into this endeavour: the angel keeps company with butches; femmes; Black, disabled and sadomasochistic (S/M) lesbians; James Dean; and the comic book character Tank Girl (among others). Stolen Glances establishes that lesbian is a fluid and capacious identification that demarcates both sameness and difference. Moreover, it registers the radical experimentation prevalent in lesbian photography during the late 1980s and early 1990s, which impacted the development of a nascent coalitional queer culture.

Reviewing Stolen Glances for British Book News in May 1992, the American photographer Tee Corinne enthused that the publication was the first of its kind and its editors the first to take a stand in advocating for a kind of lesbian visibility purposefully and agreeably complicated by difference. “Courses will be taught using it as a text”, Corinne wrote. “Researchers will use it as a starting point. Shows will be curated with it as a resource. The editors are to be commended. Let us use it as inspiration and move on”.2 Corinne (herself a contributor) demands momentum, especially in the form of further work by and for women of colour and older lesbians. Though the project was devised in an intersectional and proto-queer spirit, Corinne’s anticipatory statement is yet to be fully realised. In the thirty years since its publication, Stolen Glances has been more of a cult object among lesbians, queer people, and photography scholars than a foundational teaching text. But Corinne’s prediction has proven more accurate for some of the photographs within it, including those that make up The Knight’s Move. Alongside Angelic Rebels (1989), The Knight’s Move has become Boffin’s best-known work, and these two series are at the fore of a resurgence of interest in the photographer’s concise but brazen oeuvre, which entwines lesbian desire with queer politics. Boffin was given her first, posthumous, solo exhibition at New York’s Hales Gallery in 2023, the same year that Tate acquired Angelic Rebels for its permanent collection and included the series in its exhibition Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990. The Knight’s Move subsequently featured in Tate’s 2024 exhibition The 80s: Photographing Britain. This follows on from Boffin’s inclusion in recent group shows across the United Kingdom (Deep Down Body Thirst, Glasgow, 2018; Resist: Be Modern (Again), Southampton, 2019; Hot Moment, London, 2020; The Rebel Dykes Art & Archive Show, London, 2021; Unlimited Intimacy, Newcastle upon Tyne, 2023), as well as further afield, namely the 2022 exhibition Every Moment Counts: AIDS and Its Feelings at Oslo’s Henie Onstad Art Center.

2Despite the push to bring Boffin into view, critical reflection on her life and work remains sparse, and this article makes an initial effort to situate her practice in the context of British art and politics as they were around the time that “queer” was reclaimed from its derogatory past and refashioned as a defiant and politicised identification. I propose that, rather than working on Boffin and figuring her as an artist on the cusp of “rediscovery”, we can work with her, taking her photographs as an invitation to adopt the queer lesbian worldview that she sought to picture. In both Boffin’s present and our own, substantial and often heavily policed lines have been drawn around the meaning of lesbian, which dovetail with those encircling “woman” and “feminist”, and are increasingly posed in opposition to “trans”, “non-binary”, and other gender-nonconforming identifications held under the umbrella of queer. Boffin understood lesbian identity from a queer perspective and worked to open it up to new interpretations and bodies. In what follows, I situate her photographs not only as records of such a manoeuvre but also as an active resource with a role to play in the world they foreshadowed. The Knight’s Move rewrites history to include lesbians while simultaneously yoking them to the queer context of its making, and demands that we look to the past as we approach our present and future. By using the same methodological tools that Boffin sets out, I argue for “the knight’s move” as a gambit that can reconstitute the potential of a queer politic tied to lesbian concerns, thereby activating her work in our present as a site of community formation. In this way, returning to Boffin—working with her—can be staged as a call to hold “lesbian” as a capacious identification and to animate it with our own wants and needs.

Queer Theory and Photographic Practices

Tessa Boffin was born on 24 December 1960 and came of age during a period of rapid social and political change. Raised in a village outside Oxford, she left her local state-run secondary school in 1979. In 1983 she began a BA in Photographic Arts (Theory and Practice) at the Polytechnic of Central London (PCL), studying with lecturers who would become key to the articulation of what has become known as photo theory, including Victor Burgin, Simon Watney, and Mitra Tabrizian, and in the wake of Jo Spence’s time on the course as a mature student. In 1972 PCL became the first British institution to offer a degree (as opposed to a certificate) in photography. This marked a seismic shift in how photography was taught, elevating the stature of the medium and pulling it away from a craft-based model of art education, where “theory” had referred to developing times and chemical ratios.

Burgin joined PCL in 1973, and under his leadership the photography programme became a hub for the kind of photo theory he later mapped as an ascendent field in his 1982 anthology Thinking Photography. The BA in Photographic Arts matured in the wake of the 1960 Coldstream Report, which significantly altered how art was taught and assessed at university level in the United Kingdom. One change was the inclusion of compulsory education in the form of art history, or “complementary studies”, which gave figures like Burgin permission to orient fine art pedagogy in relation to relevant histories and frameworks. At PCL, photography students were trained to work with the medium through a theoretical approach that emphasised how it functions as a tool of communication and is bound to ideology. Photo theory drew from film and cultural studies, each inflected by feminist and postcolonial discourse, as well as from psychoanalysis and semiotics.3 Culture was understood as a site not only of indoctrination but equally of potential disruption. As the photography theorist and AIDS activist Jan Zita Grover explains in a special issue of the American magazine exposure dedicated to this “British Photography”, what was at stake was the contention that photographs “structure our sense of how the world operates: who has the power, how they keep it, how it can be more equitably distributed”, leading to a view of photography “not as an act of individual self-expression, but as a social practice”.4 Drawing from feminism, this coalesced around the “politics of representation”, the theorisation of which underpins Boffin’s practice. In a 1988 letter printed by the journal Feminist Review, Boffin acknowledges the importance of this term (and of Burgin) outright, explaining that she is not interested in trying to represent politics, which she characterises as the kinds of documentary practices aimed at capturing “marches, or ‘positive images’ of women”.5 Rather, she describes her work as being “within representation” and interested in “how meaning is constructed in photographs or subjectivity produced”.6 This absorption of photo theory is further evidenced by Boffin’s use of photography to visualise lesbian difference apart from the idea of a singular, idealised feminist subject, and demonstrates the centrality of this new school of British photography to renegotiating the story of queer’s emergence as a politicised identification in the United Kingdom.

3Boffin continued her studies, and in 1987 began an MA in Critical Theory at the University of Sussex.7 Here she studied with scholars including Jacqueline Rose, Geoffrey Bennington, Cora Kaplan, and Jonathan Dollimore. The course approached theory and topics such as sexual difference from the vantage of poststructuralism and the likes of Lacan, Foucault, and Derrida. These academic credentials are important to understanding Boffin’s practice: both the student work she made while on her BA and MA courses and that which followed as her interests were consolidated by the nascent queer moment. Where at PCL she had been exposed to critical debates regarding how photographs are bound to systems of knowledge and power, at Sussex this analysis was deepened through consideration of the text in a broader sense, including but not limited to photography. Her artistic work is steeped in this flavour and attended by the notes, handwritten essays, and annotated xeroxes that are now kept in her archive.8 Early series, concerned with topics such as romantic heartbreak and (registering the mentorship of Watney) the AIDS epidemic, matured into critical investigations of lesbian history and politics, coinciding with Boffin’s own process of coming out as lesbian in her twenties.

7Later works, including Angelic Rebels, The Knight’s Move, The Sailor and the Showgirl (1993), and The King’s Trial (1993), register Boffin’s engagement with feminist debates around the ethics of sexuality and desire known as the “sex wars”.9 In the wake of women’s liberation, heated and divisive arguments developed between what have been historicised as two polarised camps: one against pornography, S/M, penetrative sex, and butch/femme (among other “male identified” proclivities), and one for them, often termed (and, in Boffin’s case, self-identified) as “sex radicals”.10 Sex radicals experienced the sex wars as an attempt to police their gender and sexuality, with some factions labelling them as not “real” feminists or lesbians and perhaps not even “real” women. These fractures were intense, as were the pressures loaded onto public-facing figures such as Boffin, whose work served to further galvanise these debates and remains for some a site of ambivalence.11 The long shadow of the sex wars can be seen in contemporary debates regarding the rights of trans, non-binary, and gender-nonconforming people, whose relationship to feminism has been disputed with the vigour once directed against porn and sexual fantasy.

9By cladding her angel in a leather harness, Boffin aligned her with the world of experimental lesbian sexuality being explored at S/M nights and play parties, and in conversation with gay men. This is consistent with her wider oeuvre of photographs and writing, across which Boffin argues for sexual freedom and plurality under the auspices of lesbian and feminist identification, and for the site of representation as key to producing lesbian desire and sex-radical subjectivity. At the same time, she established herself as a fixture in London’s dyke scene and in the wider landscape of British queer activism, where she was a member of the direct action group Outrage! Following Boffin’s suicide in 1993, the artist’s friend Cherry Smyth penned an obituary and appreciation. Smyth recalls that

12In the summer of 1991, I returned from New York, buzzing with the exhilaration of a new political movement which promised to embrace gender and race in a fight to challenge homophobia and heterosexual privilege. I wore my “Queer Girl” badge with attitude, confounding and collapsing the label of “lesbian woman” with glee. Later Tessa was to return from New York wearing a “Queer Boy” badge, riding the edge of gender-fuck out further than I could. She described herself at that time as a queer dyke.12

In both her life and work, Boffin played with language and visual codes, re-signifying what “lesbian” meant or could yet be made to mean, and her achievements as an artist and organiser were central to radical queer thinking as it emerged in Britain in the early 1990s. Following the directive to consider photography “as a practice of signification” bound to “specific materials, within a specific social and historical context, and for specific purposes”, and in step with queer’s disintegration of discrete binaries, Boffin began to experiment with the medium’s plasticity as she considered the construction of lesbian sexuality and gender. As Watney explains, the reclamation of “queer” from its application as a term of abuse was not solely intended to transform the word into a defiant and dissident identification, what he describes as “queers asserting their queerness”.13 Rather, he highlights that “queer” directed its users towards “contesting the overall validity and authenticity of the epistemology of sexuality itself”, a task that Boffin undertook by simultaneously interrogating the ontology of photography.14

13Stolen Glances

In addition to her own photographic work, Boffin collaborated on two publications, Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology and Stolen Glances, both of which had double lives as exhibitions that toured to galleries across the United Kingdom (and the former to Canada).15 On Ecstatic Antibodies Boffin collaborated with Sunil Gupta and on Stolen Glances with Fraser, who had also been an initiating member of the Ecstatic Antibodies team. Both projects feature works by their co-editors, as well as from a range of invited photographers and writers.16 While the exhibitions that coincided with both books were crucial to how these expansive projects circulated and to their impact on British lesbian and gay culture during the early 1990s, here I focus on Stolen Glances’ published form. This is how subsequent generations have, until recently, been introduced to Boffin and Fraser’s work: not as photographs on a wall but as a bound volume of increasing rarity, the density of which dramatises its effort to diversify and denaturalise the image of what a lesbian looks like.17 Grover described Stolen Glances as a reparative turn in the visualisation of what “lesbian” could be made to mean, and in her own essay for the book she writes, of the photographs selected by Boffin and Fraser, that “where scarcity existed, they propose plenitude: tattooed women, non-thin women, women of colour, physically disabled women, butch women, femme women”.18 Stolen Glances features work by twenty-nine contributors, including Ingrid Pollard, Rosy Martin, Deborah Bright, and Del LaGrace Volcano, whose photographs sit alongside texts by theorists and poets including Mandy Merck, Johnny Golding, and Jackie Kay. (The exhibition whittled this selection down to ten.)

15Though Stolen Glances includes Boffin and Fraser’s American and Canadian peers, attesting to London’s queer links with North American hubs including Toronto, Vancouver, San Francisco, and New York, the context for the project was uniquely British. Its introduction outlines the moment of its inception in the aftermath of Section 28, an amendment to the Local Government Act 1988 made by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government that prohibited local authorities from “promoting homosexuality” and “the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship”.19 Boffin and Fraser describe the immediate fallout, “disappointed that we had not succeeded in preventing it from being passed into law, yet exhilarated by the increased sense of lesbian and gay community that those struggles had engendered”. They continue, writing that, inasmuch as “Section 28 legislates against ‘the promotion of homosexuality’; we felt that promotion was precisely what was needed”, a need that coincided with an influx of “exciting” lesbian photography in the United Kingdom and North America, inventive work that “had ‘stolen’ and inverted the meanings of mainstream, heterosexual imagery” and captured their imaginations.20 Crucially, Stolen Glances also responded to the sex wars, and the photographs selected by Boffin and Fraser reflect resistance to these simultaneous pressures. Laid out across four sections (Historical Perspectives, Pretended Family Albums, Subverting the Stereotype, and Signs of Erotica) is an array of assertive, innovative, diverse, and at times provocative work. Responding to the discourse of “the real” as it was mapped onto the lesbian body, Boffin, Fraser, and their contributors used photography to, as Laura Guy explains, make “the crucial insight that the denaturalisation of lesbian identity could engender the same for the medium of photography”.21 John Roberts has written that photo theory (pulling from earlier thinking around photography by the likes of Walter Benjamin and Bertolt Brecht) offered the means to understand that photographs “did not reflect the world but constructed our view of it”.22 Stolen Glances brought together staged photography, photomontage, and photo-text work to make the related point that “lesbians are not a coherent type”.23 On the one hand, it highlighted how photography could be used to undermine the charge of “pretended family relationships” on which Section 28 was founded and that hinged on the idea that lesbian and gay couples were less “real” than a heterosexual standard. On the other, it spoke back to a feminist ideal of lesbian sexuality as “pure” and unfettered by the explicit desires more commonly attributed to men, a charge that was extrapolated to suggest that sex radicals were not “real” lesbians. A year after its publication, Boffin reflected that “we didn’t call it queer at the time, but looking back on it that’s what it was”.24

19The Knight’s Move

In addition to compiling Stolen Glances, Boffin contributed her series The Knight’s Move. The work shares its name with a 1923 essay collection by the Russian formalist Viktor Shklovsky, whose writing was assigned to students on Boffin’s course at Sussex. In the preface, Shklovsky describes the aftermath of the 1917 October Revolution. He had fled the country in 1922, when his background in the Socialist Revolutionary Party was discovered by Bolshevik elements, exposing him to the threat of arrest. Shklovsky paints two pictures of the country he left behind: one where people starve in the streets and resort to cannibalism and the other where universities flourish and theatres are full. “All this is true”, he says. “There is this in Russia, but also that”.25 Shoring up how lived experience buckles under the weight of political idealism, he posits the knight’s move as a means of making this complex dynamic visible, writing that “the knight is not free: it moves sideways because it’s forbidden to move freely”, making L-shaped jumps around a chess board rather than forward advances.26 It circumvents direct or literal narration in favour of more oblique ways that are suited to both artistic and political needs and, as Peter Wollen puts it, is “sometimes aggressive, sometimes defensive”.27 But Shklovsky counsels that moving sideways is not cowardly: “Our broken way is the way of the brave, but what can we do if we have two eyes each and if we can see more than the honest pawns and the kings, who are duty-bound to have but one belief”.28 Across a series of seven photographs Boffin’s The Knight’s Move imagines what our history—and therefore our present—would look like if the figure of the lesbian could be found within it and recuperated, in spite of the pawns and kings who have marched straight past her.

25The series is composed of two diptychs and three stand-alone photographs, accompanied by a short introductory poem and an essay. Together, these elements probe the relationship between photography and reality with an eye to the lack of historical precedent for situating lesbian identity, keeping with Boffin’s “intense frustration” that reality is privileged over fantasy in the construction of sexual subjectivity.29 Rather than privilege “real” evidence, the series favours a speculative account that counters the scarcity of lesbian representations, in order to augment the range of “historical lesbian images upon which to model our psychic or social selves”.30 As Boffin explained in Feminist Review, this was what she conceived of as work within representation, here interrogating how meaning is produced through photographs by attending to their very lack.

29In the poem that opens the series, Boffin writes that “I could hardly find you / in my history books / but now in this scene / you all come together”, “you” indicating a nebulous group of fabled lesbians from the past.31 The Cemetery shows five printed pages strewn among the bushes at the foot of a stone angel, which stands to the side of a wooded path running through Abney Park Cemetery in the north London neighbourhood of Stoke Newington, then a known cruising ground (fig. 2). These pages depict the “famous and not-so-famous lesbians” to which the poem refers—the modernist titans Gertrude Stein, Janet Flanner, and Sylvia Beach—as well as two photographs by Alice Austen.32 “Photography”, Boffin begins the accompanying essay, “with its supposedly intimate connection with reality, is inevitably viewed as a documentation of the ‘Real’, never (heaven forbid) as a fantasy. I wanted to throw this equation into question by looking at how our identities as dykes are constructed through historical role models, both in fact and in fantasy”.33 By reconstituting lesbian time as something that can be worked into, the photographs press on the past to account for the present and future, and manifest tangible alternatives to an otherwise homogeneous lesbian identity.

31

By way of accounting for her constructive approach to history, in the text that runs alongside Stolen Glances Boffin cites Stuart Hall’s 1990 essay “Cultural Identity and Diaspora”, a reference that gestures to the dense connections between photo theory and cultural studies.34 Hall suggests that when a shared cultural identity eludes straightforward rediscovery its histories can instead be creatively retold. Which is to say, when a history was never written, or archives never kept, reconstituting the past must happen on different, more flexible, terms. This manoeuvre acknowledges what Boffin terms the “ruptures and discontinuities underlying the supposed unity” of communities that are “not a coherent type”—too diverse to be distilled into a single image or idea—and that demand “imaginative discovery” to counteract the forces that have worked to obscure them, what she calls the knight’s move.35 While not discounting the importance of “real” evidence, Boffin insists that

3436we must not be content solely with delving into the past in order to find consoling elements to counteract the harm and under-representation, or mis-representation, we have suffered as a marginalised community. We cannot just innocently rediscover a lesbian Golden Age because our readings of history are always a history of the present, shaped by our positions in the present. We also have to re-invent; we have to produce ourselves through representations in the present, here and now.36

Hall foregrounds that cultural identity as a matter of becoming as much as it is of being, a distinction that privileges identification over identity and positions it as a future-oriented process. The Knight’s Move operates on similar terms, visualising Boffin’s call to “produce ourselves” by inserting the lesbian into supposedly incongruent histories and chiming with what Grover terms in her own essay as an “alternative/enhancement” to what have otherwise been defined as the parameters of lesbian life.37

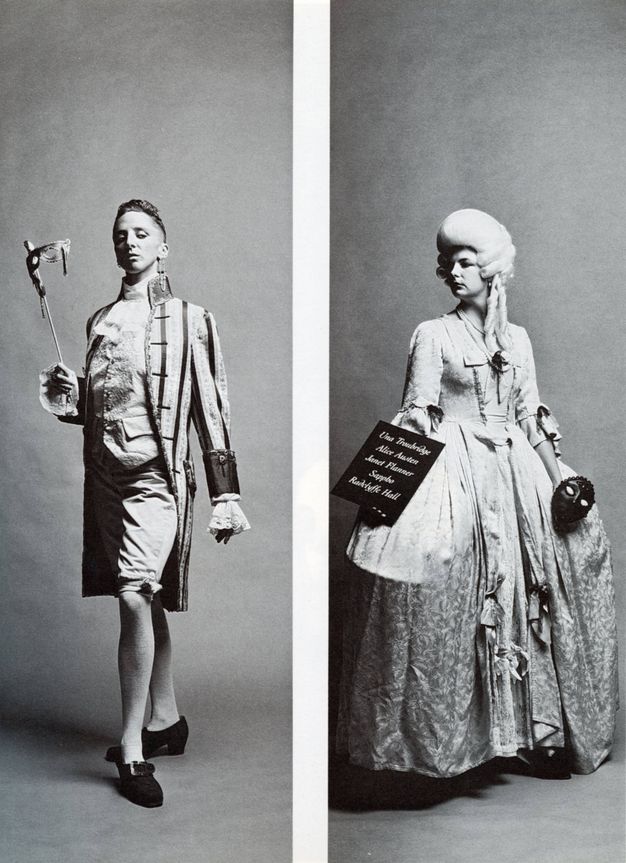

37Moving off the path and into a studio, Boffin opens the series onto a sequence of staged images that see friends and figures from London’s sex radical scene dressed as historical types: a knight, a knave, a Casanova and a lady-in-waiting, as well as the queerly attired angel.38 Their costuming and pose are formal and self-conscious, heightening the sense that the photographs are not candid documentation but were staged for the benefit of Boffin’s camera. The appearance of these figures, out of time and yet on the record, destabilises the medium’s claim to veracity and works into the histories from which the lesbian has been excluded. By locating her within them—a knight’s move that oscillates between temporalities—Boffin undermines the convictions of “straight” photographic time. This is underscored by the presence of the angel. While her leather harness positions her within the context of a nascent queer scene, she is unmoored from history, bridging a constructed lesbian past with her queer present.

38The first two portraits are presented as a diptych, a knight and knave in historical dress posed against a grey backdrop (fig. 3). Turned at a three-quarter angle, the knight clasps the hilt of her sword and the knave a dagger, both with their left feet turned out in a firmly grounded stance. The knight is recognisable as a butch lesbian only in contrast to the knave, who wears her hair at a more conspicuously “feminine” length and carries a placard with another list of historical icons: Queen Christina of Sweden, the playwright Natalie Barney, the painters Gluck and Romaine Brooks, and the early Hollywood director Dorothy Arzner. A second diptych follows, jumping forward to a Casanova and a bewigged lady-in-waiting (fig. 4). With shoulders confidently thrown back, the Casanova lifts a Venetian-style demi-mask away from her face to reveal a haughty and impassive expression. The lady-in-waiting looks towards her, holding a placard with yet another list: Radclyffe Hall’s partner Una Troubridge, Alice Austen, Janet Flanner, Sappho, and Hall herself. These four characters are at once realistic, given some familiarity with period dress, and at the same time evidently characters, a point heightened by the not quite neutral environment of the studio and the incongruity of the placards against an extravagant mix of armour and brocade. Smyth writes that the placards are proffered “as if to ensure that these images will not be recuperated and lost to a heterosexual, historical narrative”.39 Boffin inserts the lesbian into unfriendly histories but prevents the photographs from slipping into the realm of straightforward re-enactment, making them strange by including markers that draw the viewer’s attention to their location in her present.

39

The knight’s move is a sideways jump that can travel backwards or forwards, leapfrogging the other pieces on a chessboard. Though it can’t make direct moves, the knight carves out its space, wheedling its way into the game by hurdling over the rank-and-file legions of pawns, bishops, and rooks. Whereas they play in one dimension, on a single line, the knight plays on two. This is Shklovsky’s point, that in spite of its limitations the knight’s unique liberties offer it a wider view of the game at hand. In the context of Boffin’s series, this move is an oblique turn into history, which she employs to break through its stagnant rehearsals. Rather than travel backwards in a straight line, towards the irrefutable proof that would allow us to “rediscover a lesbian Golden Age”, Boffin takes the long way round, sidestepping convention and vaulting over disbelief. Her photographs mark out a path towards what we might have been and could then yet become. What would happen if a lesbian Casanova could be placed in eighteenth-century Italy? How might this alter the shape of modern lesbian consciousness? Guy elaborates, explaining that “here, history is something that is necessarily open to constant reinvention if it is to sustain lesbian life against the oppressive forces and devastating effects of cultural hegemony”.40 By moving sideways, this reinvention becomes possible.

40

The last image brings all five figures together in a composite that sees the studio portraits superimposed onto the cemetery landscape that opens the series (fig. 5). On the left the knight and knave hold their ground, while on the right the lady-in-waiting gently places her palm atop the Casanova’s. The Casanova holds the hand of the angel, who is positioned higher than the historical four, creating a triangular formation. She raises her right fist defiantly in the air and now gazes openly ahead. Time is compressed and history led into the present (and perhaps future) by the angel, whose S/M harness signals the sex-radical milieus of which Boffin was a part. Contrasted by the sculptural angel behind her, this angel of the 1990s is dynamic and protean, cutting across the periods Boffin determined to be missing from lesbian history. She describes the knight’s move as a method of “embracing our idealised fantasy figures, by placing ourselves into the great heterosexual narratives of courtly and romantic love”, a gambit prompted by the mood of lesbians disenchanted with the lack of sexual possibility in the available representational repertoire.41 Challenging linear time, the horizon opened through the work’s hybridisation is what Grover describes in Stolen Glances as “photographs hurled toward the future, cast ahead of us as visual guideposts to what we hope to become”.42 This future might now be identified as our queer present, which Boffin argued was tied to the manifold interests of lesbian desire.

41

Rewriting the Future

At the start of this article, I describe Boffin’s queer angel as the angel of a lesbian history. The work of Walter Benjamin was central to the photo theory in which Boffin trained, and “hurling” photographs towards the future evokes Benjamin’s vocabulary in “Theses on the Philosohy of History”, in which he famously names Paul Klee’s 1920 monoprint Angelus Novus as the “angel of history”. Benjamin interprets Klee’s angel as a figure turned towards the past, characterised as “one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet”. The angel “would like to awaken the dead, and make whole what is smashed”.43 But it is trapped in the storm of progress that seems to move history forward. The angel can only watch as the rubble piles higher, disasters that might have been avoided if only we could fold them into the always receding present as mistakes yet to be redeemed.

43“Benjamin thought that the past could be transformed by what we do in the present”, Terry Eagleton writes, but “not literally transformed, of course, since the one sure thing about the past is that it does not exist”.44 We cannot reach into history and alter its course, but staging photographs like the knight and the knave can allow us to see it differently. We can listen to history and tend to its interpretations (or lack thereof), which is the task undertaken by Boffin in The Knight’s Move. The angel ruminates on the disasters and desires thrown before her, lessons that we have failed to learn from the erasure of lesbian happiness, diversity, and eroticism. But if there is wrapped into her person a feeling of Benjaminian melancholy—her downcast gaze, the self-protective gesture marked by one arm wrapped around her midriff, the pause in her stance—we might interpret the catastrophe to which she bears witness as queer itself. Heather Love writes that “when queer was adopted in the late 1980s it was chosen because it evoked a long history of insult and abuse—you could hear the hurt in it”.45 Parallel to this, “lesbian” was developed, embodied, theorised, and disputed, a process to which Stolen Glances testifies. The book registers the hesitancy expressed by some lesbians towards assuming the mantle of “queer” on the basis of not only the “hurt” that Love describes but also the suspicion that it would become a synonym for “gay”, erasing the differences and particularities of sapphic identity.

44The pamphlet Lesbians Talk Queer Notions, which Cherry Smyth published the same year as Stolen Glances, records this feeling. Staged as a wide-ranging conversation among an “international group of activists and their critics”, it draws together a range of opinions on whether “queer” and “lesbian” can be aligned.46 Tori Smith, a contributor, expresses her hope that “the fact that feminists pioneered a lot queer ideas doesn’t get lost, so it becomes seen as something that only grew out of ACT UP or men’s ideas”.47 The film-maker Pratibha Parmar emphasises the importance of specificity, explaining that “I say ‘I’m KHUSH’, and that’s from talking to Indian gay men and lesbians and finding that we want to find another word for ourselves that comes from our own culture. But I have used queer in the context of other queers”.48 Philip Derbyshire chimes in from a gay perspective to note that “queer offers the terms of transgressive and subversive, but transgressive of what? Subversive of what?”49 His questions resonate with Simon Watney’s insistence that the word’s reclamation should not end with ‘’‘queers’ asserting their queerness’", and carries through to its interrogation by David L. Eng, Jack Halberstam, and José Esteban Muñoz, who go on to ask in a 2005 special issue of Social Text: “what’s queer about queer studies now?” Eng, Halberstam, and Muñoz argue for “queer” as “a metaphor without a fixed referent”, a call not dissimilar to that made by Boffin and Fraser with regards to “lesbian” and that indicates the extent to which “queer” itself became saturated with stereotypes and expectations.50

46Boffin’s angel thus calls on us to remember the transitional period which marked queer’s reclamation was not simply a matter of surrendering older words for new ones. The danger of relinquishing “lesbian” (and “feminist”) was understood. Wrapped into queer’s present is a lesbian history interlocked with a queer past, a detail revealed by the final composite frame of The Knight’s Move but visible only from the vantage of the future it had begun to imagine. Raising her fist aloft in this final image and guiding her cadre of historical figures forward, the angel stakes a claim on both identifications (which, as Hall reminds us, are always in process), defiantly facing the complex depths of lesbian history and asserting them as a framework for the comparative happiness that can appear when lesbian and queer desires are fused.

Benjamin suggests that “to articulate the past historically does not mean to recognise it ‘the way it really was’. It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger”.51 If Benjamin can help us to locate the urgency of Boffin’s queer angel, a return to Shklovsky can help us to understand how this figure operates relative to the time of the photographs in which she resides. The Knight’s Move posits history as something to be worked with rather than on, a directive that photography’s pliable nature can facilitate. The photographs (like the knave and the Casanova) are time travellers, and by staying with Boffin’s own interventionist approach to “articulat[ing] the past historically” we can use the knight’s lateral jump as a means of attending to how her photographs appear in our present.

51The knight’s move works towards something that is out of reach given the path of a straight line. It thus operates as a tool both for breaking into photographic time, to alter the way that history is told and received, and for “producing ourselves”, as Boffin suggests, alongside photographs in the here and now. Assessing photography’s truth claim and evidentiary value, Kaja Silverman offers that a Barthesian account (wherein a photograph stands not only for what has happened in its present but as the mechanism by which its subjects’ deaths are foretold) “renders the future as unchanging as the past”. She identifies this condition as central to "the political despair that afflicts so many of us today: our sense that the future is “all used up”.52 Conversely, Boffin pulls us sideways into a recent past where our present is imagined differently, a collapse of linear time that encourages us to reframe history as a site of latent community. Neither the past nor the future is “used up”; rather, they remain open to reinvention, a proposition that exceeds Boffin’s own historical speculation and positions the series as something that can itself be brought forward.

52This knight’s move is also a means of addressing how we relate to Boffin as a queer-lesbian artist. Reviewing Brave, Beautiful Outlaws, a 2019 exhibition of the American photographer Donna Gottschalk at New York’s Leslie Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, Ariel Goldberg offers a valuable critique of the mechanisms by which queer art is recuperated. Goldberg cautions that

53to frame Gottschalk as “unsung” or finally achieving “fame”, as certain mainstream critics have done, fails to admit her resistance to normative culture. The commercial art world’s appetite for “queer images” in the service of the market’s relentless feasting on the new has already led to Gottschalk being labelled as a “discovery”. To characterise her thus is to risk dispossessing her of the nuanced relationships and communities she captures in her images. As her loved ones featured in “Brave, Beautiful Outlaws” generously reveal themselves to Gottschalk’s camera, they ask that we cultivate a richer, more detailed narrative of their lives. In that way, we might not congratulate ourselves for rescuing them from obscurity, but instead focus on the way history erases society’s most vulnerable.53

This chimes with descriptions of Boffin as having “vanished from history” and someone “you’ve likely never heard of”.54 Goldberg highlights how, when applied to dissident artists (queers, people of colour, women, the aged, and the differently abled), the framework of “rediscovery” simultaneously works to obscure and reinscribe the conditions by which they have been held apart from the critical attention that might otherwise have sustained them during their lifetimes or earlier in their careers. Like the writing of history against which Benjamin’s angel struggles, the twinned move of discovery/effacement privileges progress at the expense of staying with the complexity of difficult feelings and memories. Gottschalk’s work is a careful invitation to intimacy with her friends, lovers, and family. It demands the kind of relationality that Benjamin posits as redemptive, wherein the time of history—here figured as the time of the photograph—is not static but a livewire that pulls pasts, presents, and possible futures into view. By accessing photographs through their affective surplus, which moves us beyond their surface and towards a flash of recognition, we can read our own investments, politics, and hopes alongside those that saturate each frame. This is, as Boffin might call it, the work of “imaginative discovery”, which holds the very real power of uncovering “hidden images and histories” alongside a need to retell the past in such a way that the conditions of the present are simultaneously foregrounded.55

54Since the moment during which Boffin’s photographs were made and first circulated, “queer” has been repeatedly evacuated of its radical frissons and charged with subsuming the specificity of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and non-binary, not to mention the culturally specific terms used to describe sexual and gender dissidence around the world. At the same time, “lesbian” has been made to stand as “a label chosen by progenitors who lived in a simpler time with stricter gender boundaries”, rendering queer a more capacious (and oftentimes more desirable) term.56 Our present—our moment of danger insofar as these words are concerned—has seen the collapse of lesbian history into “gender-critical” ideology, and the charge that “lesbian” cannot account for the intersectional multitudes that “queer” (itself compromised) claims to confidently hold.57 But Boffin anticipated a future where lesbian and queer would be productively enmeshed in the service of not only lesbian sexuality, but also lesbian gender. By reactivating the desires that her work indexes and evokes, the community she pictures expands into our present.

56Boffin’s practice is exemplary of the ways in which British art in the 1980s and early 1990s rubbed up against the reclamation of queer, which promised to mean something fluid and unfixed. In this sense, if Tessa Boffin had not existed it would have been necessary to invent her, and construct her image in much the same way that she did those of the knight, the knave, the lady-in-waiting, and the Casanova. Rather than “discover” her on the terms of “a shared, collective culture which can be uncovered, excavated, [and] brought to light”, Boffin’s writing invites us to approach her work with an eye to reinvention and to creating the kinds of future images that Corinne anticipated would stem from the generous groundwork laid by projects such as Stolen Glances.58 The knight’s move defies an idea of history as something that can be lost and found, and when read back onto Boffin’s own photographs it invites us to reassess the queer lesbian politics that she sought to communicate. What does the figure of the butch knight, who can also be read as trans masculine, allow us to become? What worlds can we build from the promise of the dandy Casanova, who might yet take on an Orlandoesque/genderless bravado? Or the lady-in-waiting, whose femme exuberance nudges lesbian towards a very different kind of gendered identity? And what of the angel? What possibilities does she lead us towards and in which direction does she ask us to face? The photographs solicit us to rethink not only their past but also our present, and demand that we hold “lesbian” and “queer” as active, vital, and malleable terms.

58Acknowledgements

Thank you to the many friends and colleagues who have provided feedback on this work (in its various guises) over the course of years. Particular thanks are due to the two peer reviewers whose comments moved this article forwards and to the team at British Art Studies for their careful attention throughout the publication process.

About the author

-

Flora Dunster is a Senior Lecturer at Central Saint Martins, where she is course leader of MA Contemporary Photography; Practices and Philosophies. She works on histories of queer and lesbian photography in the United Kingdom. She is co-author with Theo Gordon of Photography—A Queer History (Octopus/Ilex, 2024). Her writing can also be found in the journal Third Text and in The Routledge Companion to Global Photographies and Resist, Organise, Build: Feminist and Queer Activism in Britain and the United States during the Long 1980s, among other publications. She is co-editor of this special issue of British Art Studies with Fiona Anderson, Theo Gordon, and Laura Guy.

Footnotes

-

1

Elizabeth Freeman makes a similar point regarding the Benjaminian undertones of the harnessed cherubs in Isaac Julien’s film The Attendant (1993) (Elizabeth Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010, 154). ↩︎

-

2

Tee Corinne, “Lesbian Photography: Tradition and Promise”, British Book News 9, no. 2 (February–March 1992), Tessa Boffin Archive, University for the Creative Arts, Rochester, NY. ↩︎

-

3

For a map of the ways in which these fields developed alongside each other and in the context of post-war British politics, see Dennis Dworkin, Cultural Marxism in Postwar Britain (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997). ↩︎

-

4

Jan Zita Grover, “Editor’s Introduction”, exposure 24, no. 3 (Fall 1986): 5. ↩︎

-

5

Tessa Boffin, “The Blind Leading the Blind: Socialist-Feminism and Representation”, Feminist Review 29, no. 1 (Summer 1988): 158. ↩︎

-

6

Ibid. ↩︎

-

7

Some of the content taught on Boffin’s course, which was housed in the School of English and American Studies, foreshadowed what would become the MA in Sexual Dissidence, established by the cultural and literary theorists Alan Sinfield and Jonathan Dollimore in 1991. ↩︎

-

8

Boffin’s archive is held at the University for the Creative Arts, Farnham. ↩︎

-

9

The Sailor and the Showgirl, which Boffin made with her girlfriend Nerina Ferguson, is sometimes alternatively titled The Sailor and the Whore. Boffin’s notes refer to the series using the latter and, when three images were included in Lesbian Looks: Postcards from the Edge (ed. Rosa Ainley and Belinda Budge, London: Scarlet Press, 1993), Boffin and Fergus titled them Two Dykes and A Straight Man, The Sailor and the Whore. ↩︎

-

10

I have written about the problems of historicising the sex wars in Flora Dunster, “Lesbians Talk: British Lesbian Politics and the Sex Wars”, in Resist, Organize, Build: Feminist and Queer Activism in Britain and the United States in the Long 1980s, ed. Sarah Crook and Charlie Jeffries (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2022), 307–28. ↩︎

-

11

Notably, and as Cherry Smyth recounts, Boffin staged a performance in 1992 titled Crucifixion Cabaret. The performance crossed several thresholds. It included both male and female performers and a public act of unprotected sex. In the dual context of the sex wars and the AIDS epidemic, Crucifixion Cabaret moved Boffin’s work in a riskier direction. Both at the time and subsequently in hindsight, viewers and members of the proximate community have recalled Boffin’s work as evoking not just the radical experimentation of the 1980s and 1990s but also the negativity associated with complex group politics against the backdrop of hostility directed towards LGBTQ+ communities by Thatcher’s Tory party. See Cherry Smyth, “Dyke! Fag! Centurion! Whore! An Appreciation of Tessa Boffin”, in Outlooks: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities and Visual Cultures, ed. Peter Horne and Reina Lewis (London: Routledge, 1996), 109–12. ↩︎

-

12

Ibid., 111. ↩︎

-

13

Cherry Smyth, Lesbians Talk Queer Notions (London: Scarlet Press, 1992), 20. ↩︎

-

14

Ibid. ↩︎

-

15

Tessa Boffin and Sunil Gupta, eds., Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology (London: Rivers Oram, 1990); Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser, eds., Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs (London: Pandora Press, 1991). ↩︎

-

16

Advertisements were placed in venues such as the Birmingham-based photography magazine TEN.8, but Boffin and Fraser noted at the ICA launch of Stolen Glances that no one had replied to them, and this led them to networking as a more efficacious way of soliciting contributors (Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser, “Stolen Glances: On the Myth of Naturalism in Lesbian Photography”, public talk at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 26 September 1991, https://sounds.bl.uk/Arts-literature-and-performance/ICA-talks/024MC0095X0762XX-0100V0 (accessed September 2021). ↩︎

-

17

At the time of writing, a used copy of Stolen Glances retails for between £43 and £65. When I purchased my copy in 2016, it retailed for one pence. This dramatic inflation illustrates the extent to which work such as Boffin’s has re-entered queer consciousness in the intervening years. ↩︎

-

18

Jan Zita Grover, “Framing the Questions: Positive Imagery and Scarcity in Lesbian Photographs”, in Stolen Glances, ed. Boffin and Fraser, 187. ↩︎

-

19

Local Government Act 1988, The National Archives, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/9/section/28/enacted. ↩︎

-

20

Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser, “Introduction” in Stolen Glances, ed. Boffin and Fraser, 9. ↩︎

-

21

Laura Guy, “Backwards Glances at Lesbian Photography”, Photoworks Annual, no. 24 (2017): 89. ↩︎

-

22

John Roberts, The Art of Interruption (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998), 148. ↩︎

-

23

Martha Gever and Nathalie Magnan, “The Same Difference: On Lesbian Representation”, in Stolen Glances, ed. Boffin and Fraser, 67. ↩︎

-

24

Smyth, Lesbians Talk Queer Notions, 51. ↩︎

-

25

Viktor Shklovsky, Viktor Shklovsky: A Reader, trans. Alexandra Berlina (London: Bloomsbury, 2017), 153. ↩︎

-

26

Ibid. ↩︎

-

27

Peter Wollen, “Knight’s Moves”, Public, no. 25 (May 2002): 54. ↩︎

-

28

Shklovsky, Viktor Shklovsky: A Reader, 154. ↩︎

-

29

Tessa Boffin, “The Knight’s Move”, in Stolen Glances, ed. Boffin and Fraser, 49. ↩︎

-

30

Ibid., 50. ↩︎

-

31

Ibid., 43. Social construction theory’s preference against imposing contemporary terminology on the past would have been known to Boffin, and her decision to label historical figures as lesbian is political, in the vein of the Lesbian History Group’s contemporaneous research project (Lesbian History Group, Not a Passing Phase: Reclaiming Lesbians in History, 1849–1985, London: Women’s Press, 1989). ↩︎

-

32

Boffin, “The Knight’s Move”, 50. ↩︎

-

33

Ibid., 49; emphasis original. ↩︎

-

34

Stuart Hall, “Cultural Identity and Diaspora”, in Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, ed. Jonathan Rutherford (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1990), 222–37. Indeed, Simon Watney refers to the “revolution in critical theory” taking place across and between disciplines as the “Cultural Studies Movement”; see Simon Watney, “On the Institutions of Photography”, in Visual Culture: The Reader, ed. Jessica Evans and Stuart Hall (London: SAGE, 1999), 141. ↩︎

-

35

Boffin, “The Knight’s Move”, 49. ↩︎

-

36

Ibid. ↩︎

-

37

Grover, “Framing the Questions”, 185. ↩︎

-

38

The models include Sophie Moorcock as the lady-in-waiting, who alongside Lulu Belliveau was co-editor of the London-based erotica magazine Quim. ↩︎

-

39

Smyth, “Dyke! Fag! Centurion! Whore!”, 109. ↩︎

-

40

Guy, “Backwards Glances”, 93. ↩︎

-

41

Boffin, “The Knight’s Move”, 49. ↩︎

-

42

Grover, “Framing the Questions”, 185. ↩︎

-

43

Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History”, in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 257. ↩︎

-

44

Terry Eagleton, “Waking the Dead”, New Statesman, 12 November 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20210726192213/https://www.newstatesman.com/ideas/2009/11/past-benjamin-future-obama (accessed 1 July 2021). ↩︎

-

45

Heather Love, Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 2. ↩︎

-

46

Smyth, Lesbians Talk Queer Notions, back cover. ↩︎

-

47

Ibid., 27. ↩︎

-

48

Ibid., 21. ↩︎

-

49

Ibid., 46. ↩︎

-

50

David L. Eng, Jack Halberstam, and José Esteban Muñoz, “Introduction: What’s Queer About Queer Studies Now?” Social Text 23, nos. 2–3 (2005): 1. ↩︎

-

51

Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History”, 255. ↩︎

-

52

Kaja Silverman, The Miracle of Analogy (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2015), 4. ↩︎

-

53

Ariel Goldberg, “Rebel Rebel”, Artforum, January 2019, https://www.artforum.com/columns/ariel-goldberg-on-donna-gottschalk-241597. ↩︎

-

54

Ksenia M. Soboleva, “How Tessa Boffin, One of the Leading Lesbian Artists of the AIDS Crisis, Vanished from History”, Hyperallergic, 17 June 2019, https://hyperallergic.com/505433/how-tessa-boffin-one-of-the-leading-lesbian-artists-of-the-aids-crisis-vanished-from-history. ↩︎

-

55

Boffin, “The Knight’s Move”, 49. ↩︎

-

56

Christina Cauterucci, “For Many Young Queer Women, Lesbian Offers a Fraught Inheritance”, Slate, 20 December 2016, https://slate.com/human-interest/2016/12/young-queer-women-dont-like-lesbian-as-a-name-heres-why.html. ↩︎

-

57

Gender-critical feminism believes that biological sex is unchangeable. It is suspicious of (or outright rejects) the idea that gender identity—the feeling of being male, female or otherwise—can shift and that a person assigned to a particular sex at birth might grow into a gender identity that does not reflect their biology. For this reason, gender-critical ideology is often understood as transphobic. For further information see Serena Bassi and Greta LaFleur, eds., “Trans-Exclusionary Feminisms and the Global New Right”, special issue, TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 9, no. 3 (August 2022). ↩︎

-

58

Boffin, “The Knight’s Move”, 49. ↩︎

Bibliography

Ainley, Rosa, and Belinda Budge, eds. Lesbian Looks: Postcards from the Edge. London: Scarlet Press, 1993.

Benjamin, Walter. “Theses on the Philosophy of History”. In Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. Translated by Harry Zohn, 253–64. New York: Schocken Books, 1969.

Boffin, Tessa. “The Blind Leading the Blind: Socialist-Feminism and Representation”. Feminist Review 29, no. 1 (Summer 1988): 158–61. DOI:10.1057/fr.1988.37.

Boffin, Tessa. “The Knight’s Move”. In Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs, edited by Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser, 42–50. London: Pandora Press, 1991.

Boffin, Tessa, and Jean Fraser. “Introduction”. In Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs, edited by Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser, 9–21. London: Pandora Press, 1991.

Boffin, Tessa, and Jean Fraser. “Stolen Glances: On the Myth of Naturalism in Lesbian Photography”. Public talk at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 26 September 1991. https://sounds.bl.uk/Arts-literature-and-performance/ICA-talks/024MC0095X0762XX-0100V0.

Cauterucci, Christina. “For Many Young Queer Women, Lesbian Offers a Fraught Inheritance”. Slate, 20 December 2016. https://slate.com/human-interest/2016/12/young-queer-women-dont-like-lesbian-as-a-name-heres-why.html.

Corinne, Tee. “Lesbian Photography: Tradition and Promise”. British Book News 9, no. 2 (1992). Tessa Boffin Archive, University for the Creative Arts, Rochester, NY.

Dunster, Flora. “Lesbians Talk: British Lesbian Politics and the Sex Wars”. In Resist, Organize, Build: Feminist and Queer Activism in Britain and the United States in the Long 1980s, edited by Sarah Crook and Charlie Jeffries, 307–28. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2022.

Dworkin, Dennis. Cultural Marxism in Postwar Britain. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997.

Eagleton, Terry. “Waking the Dead”. New Statesman, 12 November 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20210726192213/https://www.newstatesman.com/ideas/2009/11/past-benjamin-future-obama.

Eng, David L., Jack Halberstam, and José Esteban Muñoz. “Introduction: What’s Queer About Queer Studies Now?” Social Text 23, nos. 2–3 (2005): 1–17.

Freeman, Elizabeth. Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010.

Gever, Martha, and Nathalie Magnan. “The Same Difference: On Lesbian Representation”. In Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs, edited by Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser, 67–75. London: Pandora Press, 1991.

Goldberg, Ariel. “Rebel Rebel”. Artforum, January 2019. https://www.artforum.com/columns/ariel-goldberg-on-donna-gottschalk-241597.

Grover, Jan Zita. “Editor’s Introduction”. exposure 24, no. 3 (Fall 1986): 5–6.

Grover, Jan Zita. “Framing the Questions: Positive Imagery and Scarcity in Lesbian Photographs”. In Stolen Glances: Lesbians Take Photographs, edited by Tessa Boffin and Jean Fraser, 184–90. London: Pandora Press, 1991.

Guy, Laura. “Backwards Glances at Lesbian Photography”. Photoworks Annual no. 24 (2017): 85–93.

Hall, Stuart. “Cultural Identity and Diaspora”. In Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, edited by Jonathan Rutherford, 222–37. London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1990.

Hamacher, Werner. “‘Now’: Walter Benjamin and Historical Time”. In Walter Benjamin and History, edited by Andrew Benjamin, 38–68. London: Bloomsbury, 2005.

Lesbian History Group. Not a Passing Phase: Reclaiming Lesbians in History, 1849–1985. London: Women’s Press, 1989.

Local Government Act 1988. The National Archives. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/9/section/28/enacted.

Love, Heather. Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Roberts, John. The Art of Interruption. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998.

Shklovsky, Viktor. Viktor Shklovsky: A Reader. Translated by Alexandra Berlina. London: Bloomsbury, 2017.

Silverman, Kaja. The Miracle of Analogy. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2015.

Smyth, Cherry. “Dyke! Fag! Centurion! Whore! An Appreciation of Tessa Boffin”. In Outlooks: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities and Visual Cultures, edited by Peter Horne and Reina Lewis, 109–12. London: Routledge, 1996.

Smyth, Cherry. Lesbians Talk Queer Notions. London: Scarlet Press, 1992.

Soboleva, Ksenia M. “How Tessa Boffin, One of the Leading Lesbian Artists of the AIDS Crisis, Vanished from History”. Hyperallergic, 17 June 2019. https://hyperallergic.com/505433/how-tessa-boffin-one-of-the-leading-lesbian-artists-of-the-aids-crisis-vanished-from-history.

Watney, Simon. “On the Institutions of Photography”. In Visual Culture: The Reader, edited by Jessica Evans and Stuart Hall, 141–61. London: SAGE, 1999.

Wollen, Peter. “Knight’s Moves”. Public, no. 25 (May 2002): 54–67.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 14 July 2025 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-27/fdunster |

| Cite as | Dunster, Flora. “Rewriting the Future: Tessa Boffin’s The Knight’s Move.” In British Art Studies: Queer Art in Britain since the 1980s (Edited by Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, Theo Gordon and Laura Guy), by Fiona Anderson, Flora Dunster, Theo Gordon, and Laura Guy. London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-27/fdunster. |